Secure Channel Protocols#

In this chapter, we’ll see how the many cryptographic building blocks we’ve covered are put together to create secure channels. A secure channel is a system that let parties communicate with confidentiality, integrity, and authentication, over an insecure medium like the Internet.

There are a huge number of secure channel protocols. We’re only going to cover two: the ones that you’re most likely to deal directly with in a job in the IT or software fields. If you administer a web server or a VPN, you will need to know about these two protocols.

Transport Layer Security#

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is the secure channel protocol that’s used to keep web traffic secure. TLS sets up the cryptography needed to get data from point A to point B, and the data that is actually sent via TLS consists of the messages of some other non-cryptographic network protocol: HTTP for web traffic, SMTP for sending email, etc. The combination of HTTP messages sent over TLS is called HTTPS; you’ll often see the terms “HTTPS” and “TLS” used interchangeably, although, strictly speaking, they are not interchangeable.

The two communicating endpoints in TLS are designated as the client and the server. The distinction is that the client is the endpoint that initiates the protocol.

TLS implementations are found in many different kinds of software and hardware. The most familiar kinds are web browsers and web servers. Another important kind is load balancer hardware: they can act as TLS servers, handling TLS connections coming from the Internet, and communicating with their backing servers using plain HTTP.

Authentication in TLS is done by means of certificates, with certificate chains leading back to public CAs. It is notable that, by default, only the server in a TLS connection is authenticated — that is, only the client makes sure the server is genuine, not vice versa. This is partly because of practical realities: clients generally do not have the kind of easily verifiable, fixed identity that servers do (their domain names). In addition, servers often have no need to authenticate clients, if they are meant to offer a service freely to everyone on the Internet (for example, Google search).

However, TLS has support for servers authenticating clients. This configuration is called mutual authentication. Mutual authentication is only possible when the entity administering a server has some external way to verify clients’ identity; one common example is that the server belongs to a company and the clients are the company’s employees. To enable mutual authentication, the server owner must operate a CA that issues certificates to clients.

Design Pressures#

The fact that TLS is used for web traffic requires certain things of its design. Web traffic runs between an enormous variety of different parties, who cannot be expected to be previously familiar with each other. This practically requires that TLS support certificate-based PKI, using public CAs, for authentication: its design cannot expect that the two communicating endpoints have previously exchanged keys, and it cannot expect the endpoints to consult some centralized authority every time they want to communicate.

In addition, TLS endpoints may be in a wide variety of computing environments. Many of them are regular desktop computers or servers in a datacenter, but many of them are also embedded devices. It may be difficult or impossible to update their software. This results in the need for backward compatibility: TLS endpoints must be able to accommodate older counterparties. Even as the protocol evolves to newer and better versions, in order to be widely accessible, servers must be able to support different cryptographic algorithms, and different versions of the protocol.

The latter design pressure in particular has some unfortunate consequences for security, as we’ll see later in this section.

Versions#

The latest version of TLS is 1.3, standardized in 2018. However, the most widely supported version is still 1.2. There are some significant differences between the two.

Because TLS 1.2 is still the most widespread version, this section will primarily cover that. We’ll briefly discuss the changes in TLS 1.3 at the end.

You will also often see the term “SSL” used interchangeably with TLS. Strictly speaking, this is not accurate: SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) is the predecessor of TLS 1.0, which was standardized in 1999. The basic structure of SSL was the same, but the details differed significantly. SSL has been deprecated since 2015; modern web browsers will refuse to use it. Just note that you’ll still see and hear TLS referred to as “SSL”; for example, CA companies often say they issue “SSL certificates”. If you want to be accurate, always refer to TLS as TLS.

Cipher Suites#

As part of setting up a TLS connection, the client and server must agree on a cipher suite: a set of cryptographic algorithms that are used to achieve confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. The client will send the server a list of cipher suites that it supports, and the server will choose one.

If you administer a server, you can choose which cipher suites the server will accept. The choice is important: server software may accept some insecure cipher suites by default, and it’s best practice to disable those. There are online tools[cip] which will tell you whether a given cipher suite is secure.

The cipher suite must answer several questions:

How will the client authenticate the server?

How will the endpoints settle on the same symmetric key?

Which symmetric cipher will the endpoints use? Including mode and key size if applicable.

Which hash function will the endpoints use?

These are a few examples of TLS 1.2 cipher suites (there are hundreds of others):

TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA

The part before WITH specifies how key agreement and authentication are done.

ECDHE means elliptic-curve ephemeral Diffie-Hellman, while DHE means

non-elliptic-curve ephemeral DH. (Recall that “ephemeral” DH means that both

parties generate new DH keys each time.)

If, as in the last example, the part before WITH is just RSA, this means

that the client will randomly generate a value called the PreMasterSecret,

encrypt it using the server’s RSA public key (which is in its certificate), and

send that to the server. Both server and client will derive symmetric keys from

the PreMasterSecret. This type of cipher suite is considered insecure because

it lacks forward secrecy: an attacker who compromises the server’s private

key can read all traffic from any of the server’s TLS connections that use this

scheme.

The second element of the pre-WITH part of the cipher suite, if there is one,

is a signature algorithm, which the client would use to authenticate the server.

In the examples above, it is either ECDSA or RSA. Usually, the server only

has one certificate, so it will need to choose a cipher suite whose signature

algorithm is the same as the one its certificate is signed with. However, some

server software supports multiple certificates: for example, they might serve an

ECDSA-signed certificate by default, and fall back to an RSA-signed certificate

if the client doesn’t support ECDSA.

The part after WITH specifies a cipher and hash function. In the first

example, the cipher is ChaCha20-Poly1305, and the hash

function is SHA-256.

If the cipher is an AEAD, like ChaCha20-Poly1305 or AES-GCM, then the AEAD provides confidentiality, integrity, and message authentication. If the cipher is not an AEAD, like AES-CBC, then it provides only confidentiality, and the hash function is used with HMAC to provide integrity and authentication.

Note that even if the cipher is an AEAD, a hash function is still part of the cipher suite, even though it’s not needed for integrity or message authentication. Among other things, a hash function is needed for deriving keys from the output of the DH key agreement.

If the cipher is AES or another block cipher, a mode must also be specified: the

above examples show GCM and CBC. Some ciphers, like AES, must also have a

key size specified: the above examples show 128 bits and 256 bits.

TLS 1.3 cipher suites look different; we will cover those in a later subsection.

Handshake#

The process that initiates a TLS connection is called the handshake. It consists of a few messages sent back and forth between client and server. Most commonly, it looks like this:

The client sends a message called a

ClientHello. It specifies the version of TLS that it wants to use, along with a list of cipher suites that it supports. It also includes a nonce, which mitigates replay attacks.The server replies with several messages:

A

ServerHello, in which it chooses one of the client’s supported cipher suites.A

Certificate, in which it sends its own certificate, plus all certificates in the chain leading back to a root CA’s certificate.If DH is being used for key agreement, a

ServerKeyExchange, in which it sends its DH public value, along with whatever DH parameters are needed (such as a named curve). The message also contains a digital signature of the DH public value, made with the private key corresponding to the certificate, which serves as proof that the certificate really does belong to the server.If mutual authentication is in use, a

CertificateRequestto tell the client it must present its certificate.A

ServerHelloDone, indicating that it has completed its end of the handshake.

The client does the following:

It verifies the certificate chain, ensuring that each certificate has a valid signature and hasn’t expired, and that it trusts the root CA.

If DH is being used for key agreement, the client first verifies the signature on the server’s public value. It then computes the shared secret using its own private value and the server’s public value.

If mutual authentication is in use, it sends a

Certificatemessage containing the client’s certificate.It sends a

ClientKeyExchange, whose contents vary:If DH is being used, this contains the client’s DH public value.

If DH is not being used, this contains a

PreMasterSecret, encrypted using the public key from the server’s certificate. This serves as proof that the certificate really does belong to the server: if the server does not have the corresponding private key, it will be unable to decrypt thePreMasterSecret, and the handshake will fail.It sends a

ChangeCipherSpec, indicating that everything it sends from now on will be using the negotiated cipher suite and key.It sends a

Finished, which is encrypted and authenticated using the negotiated cipher suite and key. It includes a MAC tag of the transcript of the entire handshake so far; this will prove to both parties that they have seen the exact same handshake, and that there’s no man-in-the-middle interfering.

The server then does the following:

If DH it being used, it computes the DH shared secret using the client’s public value and its own private value.

If DH is not being used, it computes a key using the

PreMasterSecretfrom the client.Either way, it then attempts to verify the tag from the client’s

Finishedmessage; if this doesn’t succeed, then something about the handshake must have gone wrong, and the connection is considered to have failed. If it succeeds, the server continues to the next step.It sends a

ChangeCipherSpec, again meaning that everything it sends from now on will be using the negotiated cipher suite and key.It sends a

Finished, which is just like the client’sFinished: it is encrypted and authenticated using the negotiated cipher suite and key, and includes a MAC tag of the transcript of the entire handshake so far.

The client verifies the tag of the server’s

Finished.

Note that the handshake requires two roundtrips: two entire cycles of the client sending some messages and the server replying. This can be a problem on slow or congested networks, or if there is simply a long distance between the client and server; fixing this was a major change in TLS 1.3.

After this is done, the client and server can exchange ApplicationData

messages, which contain the actual data that they want to send (HTTP messages,

etc.), encrypted and authenticated.

The client and server each maintain a count of how many messages they have sent, and send their current message count along with each message; it is called a sequence number in this context. It is authenticated along with the message payload. The sequence number serves as a nonce for ciphers that require it, and acts as protection against replay attacks: a TLS endpoint that receives a message with a sequence number it’s already seen can just drop that message.

Many of the message types support extensions, which are additional bits of

data that not all counterparties might support. One particularly important

extension is for the ClientHello message: the client can indicate which named

curves it supports for elliptic-curve algorithms. This lets the server know,

up-front, whether it will be able to run ECDH or ECDSA successfully.

TLS 1.3#

TLS 1.3 had some major changes from version 1.2. It is gradually being deployed more widely on the Internet, though it will take time to fully take over from 1.2.

Cipher suites now only specify the cipher and hash function; the key exchange and authentication mechanisms are negotiated separately. A TLS 1.3 cipher suite therefore looks something like

TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256.A lot of cipher suites were dropped. Whereas TLS 1.2 supported hundreds of cipher suites, 1.3 only officially defines five.

AES-GCM, AES-CCM, and ChaCha20-Poly1305 are the only supported ciphers. Note that they are all AEAD ciphers; this reflects the current expert consensus that AEAD is the way forward. SHA-256 and SHA-384 are the only supported hash functions1Those are both SHA-2 variants. It’s notable that SHA-3 is not supported at all, even though it was standardized years before TLS 1.3 was. (It has not been supported in any TLS version.).

The handshake is simplified to require only a single roundtrip: the client sends some messages, the server replies with some messages, and from that point on, the client can send application data. (The trick is that the client sends an ECDH public value with its initial messages.) TLS 1.2 requires two roundtrips for the handshake.

There is no longer support for any configuration that lacks forward secrecy.

PreMasterSecret, therefore, no longer exists.DSA is no longer supported for authentication; only ECDSA, EdDSA, and RSA are supported. (Non-elliptic-curve DH is still supported for key agreement.)

Overall, TLS 1.3 is significantly simpler, allows faster handshakes, and drops support for a bunch of insecure configurations. Good news all around!

Vulnerabilities#

TLS (and its predecessor SSL) has had many, many vulnerabilities. It is complex, has an enormous number of different implementations, and has been used for a long time in very harsh conditions, so this is not surprising.

One significant category of attacks against TLS is downgrade attacks, in which an attacker interferes with a TLS handshake to make the participants use an older, less secure configuration[AR19].

The root of the problem is that the start of the TLS handshake is unencrypted and unauthenticated; the participants have no way to tell whether the messages they are receiving came from the real counterparty or a man-in-the-middle. Two major downgrade attacks are called FREAK and Logjam; both involve a man-in-the-middle tricking the participants into using weak Diffie-Hellman parameters, so that the MITM can recover the agreed-upon key.

TLS has become significantly more secure over time, which is great, but as long as older, less-secure configurations are widely supported by clients and servers, their vulnerabilities will continue to be a problem. Downgrade attacks are inherent to any protocol that supports backward compatibility among many different configurations.

When configuring a TLS server like a web server, you will have to trade off susceptibility to downgrade attacks against backward compatibility. These days, it should be OK to only allow the use of TLS 1.2 and 1.3. Most clients support at least version 1.2. This will prevent the most serious downgrade attacks.

When using a CBC-mode block cipher, TLS is vulnerable to padding oracle attacks, which we’ve seen previously. You may remember this from the “Order of Operations” section of the chapter on authenticated encryption: TLS’s decision to compute MACs on plaintext instead of ciphertext is what allows this attack. These days, ideally, CBC mode shouldn’t be used at all, and GCM should be used instead (or ChaCha20-Poly1305).

The POODLE attack[MDK14] is a particular kind of padding oracle attack that is remarkably efficient. It is enabled by using a downgrade attack to get participants to use SSL 3.0 (the last version of SSL) with a CBC-mode cipher.

The attack is mitigated by disabling the use of SSL 3.0 on web servers. In the present day, there is no reason to keep something that old enabled.

Two attacks called CRIME[Kel02] and BREACH target the use of data compression within TLS. In older times (the 1990s), people thought nothing of compressing data before encrypting it. Now, we know that practice to be insecure. Data compression works by exploiting repeating patterns in the input. In general, the more repeating patterns there are, the shorter the compressed data is. This can allow an attacker to gain information about uncompressed plaintext, if they can cause small modifications to it and observe the size of the encrypted compressed data.

To mitigate these attacks, compression should be disabled on web servers.

Partly because TLS is so complex, it is susceptible to implementation errors. These aren’t problems with the protocol itself, but rather bugs in software that implements it. The infamous Heartbleed bug, which could cause web servers to leak secret data over the Internet, was an implementation error in OpenSSL[hea].

There isn’t a great solution to this. TLS isn’t complicated without reason; it has to support a huge variety of use cases. Implementations get better over time, as bugs are discovered and fixed, and better implementation techniques are developed. The best that we can do is to keep all our software updated with security patches, and switch away from products and versions that are known to be insecure.

IPsec#

IPsec is a group of several protocols that are used to create virtual private networks (VPNs). IPsec is not the only way to create a VPN. However, it is the most common, largely because it is very widely supported by operating systems and specialized VPN hardware (often called VPN appliances).

Familiarity with IPsec is an important skillset for anyone who administers networks in professional settings. Unfortunately, IPsec is absurdly complex[FS16]. To make matters worse, the bulk of information about IPsec on the Internet is of very poor quality. It is rife with outdated information and muddled terminology. When you are looking at VPN documentation on the Internet, pay attention to when it was written — older docs are less likely to match current reality.

There is a serious lack of clear, helpful, introductory-level information about IPsec. The aim is for this section to be exactly that, with a focus on how you might interact with an IPsec VPN as part of a job.

Architecture and Terminology#

There are two important protocols to know about:

Internet Key Exchange (IKE). VPN participants use IKE to authenticate each other, and then negotiate parameters (a cipher suite, lifetimes of keys, etc.) and create shared key material. Such parameters and key material are collectively called a security association (SA).

IKE negotiates two SAs. One is used for any further IKE communcation, such as when rotating keys. The other is handed off to the next protocol.

Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) takes an SA negotiated by IKE and uses it to exchange network traffic.

“IPsec” is a broad term, and, unfortunately, different sources use it with different meanings.

The most current and accurate meaning, though, is that IPsec encompasses both IKE and ESP, along with another protocol (Authentication Headers, or AH) which can be used in place of ESP. We’ll use this meaning in this course.

Some sources, however, use the term “IPsec” to mean only the part that carries VPN traffic across another network; i.e. they exclude IKE and a few of its alternatives. This meaning comes from a previous time when key management (IKE’s purpose) was seen as something that can be separated from the VPN itself. In modern times, it’s become clear that that’s not the case: trying to keep these concepts separate makes things more complex and less secure. We will not use the term “IPsec” like this in the course, but you should be aware of this usage in case you see it elsewhere.

Some of this terminology confusion is clarified in the “document roadmap” RFC, which serves as an index to the many other RFCs that define parts of IPsec [ips11].

VPN Basics#

In this course, we’ll avoid going into detail about the networking aspects of IPsec and VPNs (such as the question of how the OS makes sure that packets get to their correct destinations) and focus on the cryptographic aspects of IPsec. But we do need to cover the basics of VPN networking.

From the perspective of an OS and the applications running on it, a VPN connection looks just like a local network connection, such as an Ethernet or Wi-Fi network connection. All of these are things that say, “I can send and receive packets going from or to such-and-such IP addresses”.

However, whereas Ethernet and Wi-Fi connections send out packets as-is through the underlying physical hardware, a VPN connection encapsulates the packets. It encrypts them and puts the ciphertext into a new packet with a different destination address, which is part of the connection’s configuration. The new packet is sent out through the appropriate physical-hardware network connection. Then, the machine at the new destination will decrypt the packet and deliver it to its original destination.

You’ll often hear VPNs described as “tunnels”. They create the illusion of a direct connection between two machines, even though the actual traffic on this connection is passing through a wide variety of other points on the Internet and local networks.

In the VPN context, there isn’t as clear a concept of “clients” and “servers” as there is in TLS. Instead, all machines participating in a VPN are generally referred to as peers.

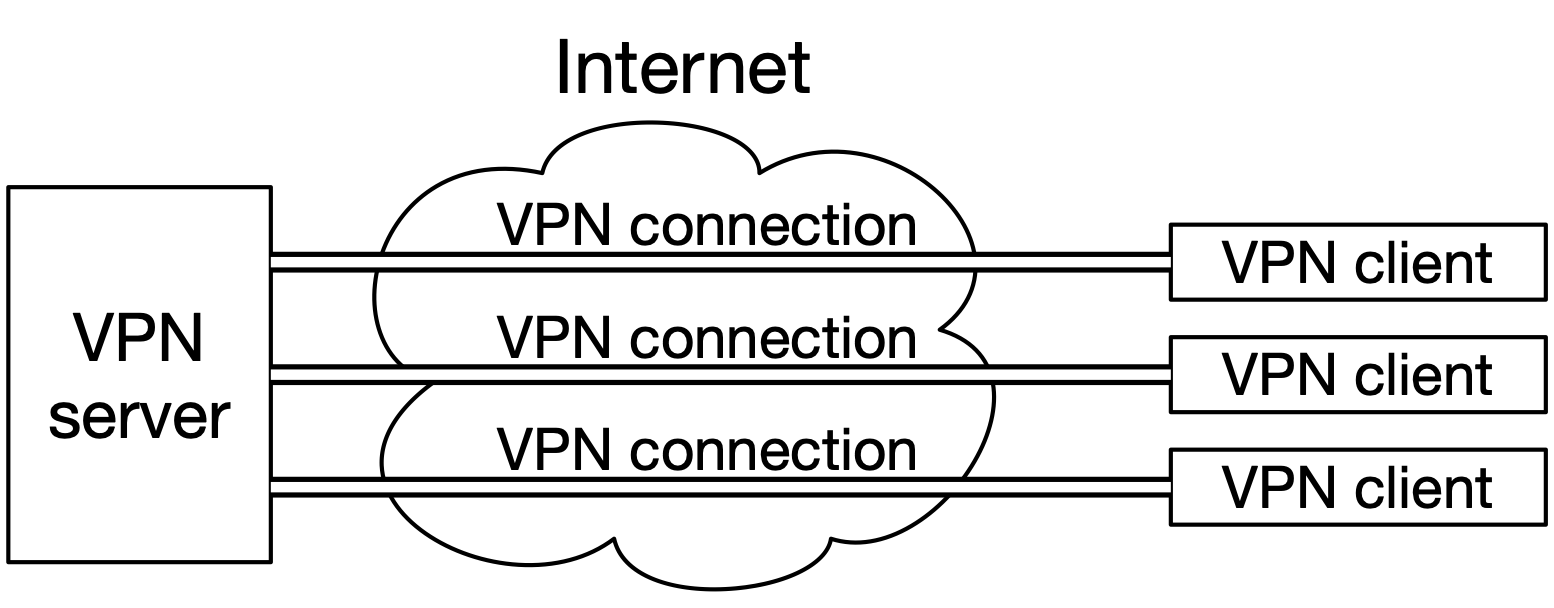

Some VPN configurations classify peers into “clients” and “servers”, such as a company’s VPN for employees to access the internal network remotely: a machine in the company’s datacenter is the “server”, and devices belonging to the employees are the “clients”. This is also the way public VPN services2The kind of VPN that people use to get around geographic restrictions on website visitors, for example. are configured. This is sometimes called a hub-and-spoke VPN. See Fig. 20.

Fig. 20 A hub-and-spoke VPN.#

Applications on the clients can talk to the server as if over a local network connection, when in fact the traffic on the connection may take a complex route over the Internet. The server may be configured to forward clients’ network traffic to the Internet, allowing the clients to access the Internet as if they were physically located where the server is; public VPN services do this.

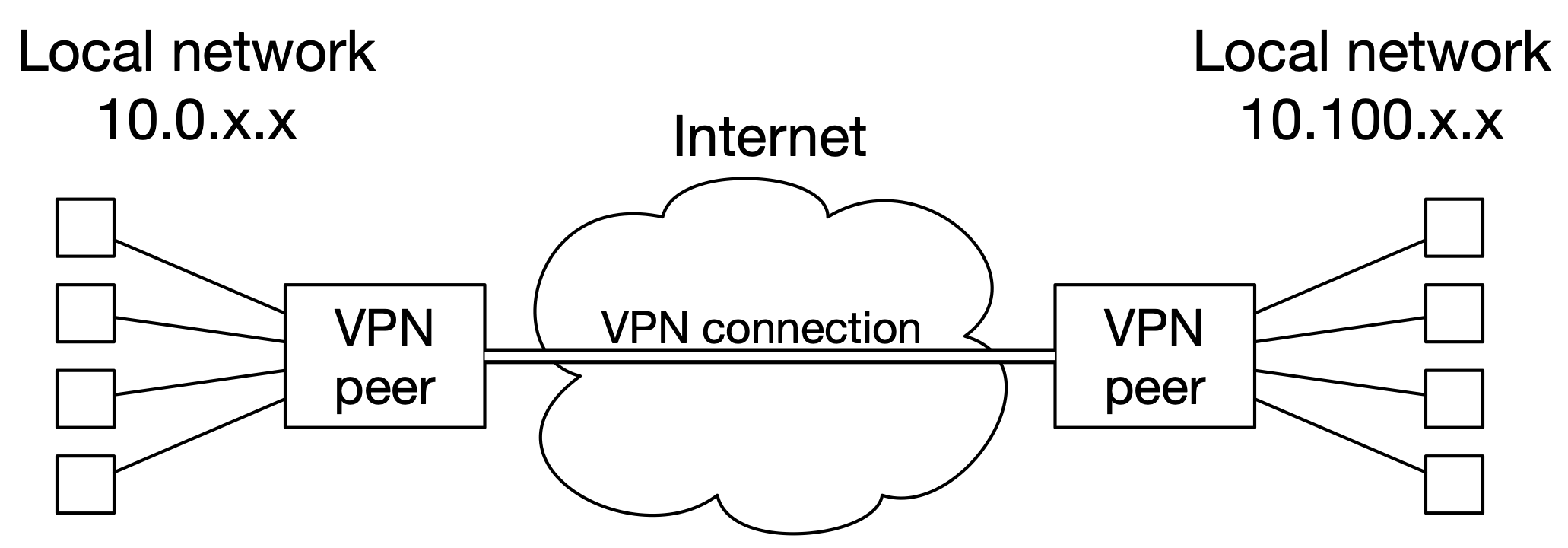

Another common configuration is called a site-to-site VPN, which involves only two peers. The purpose is to join two separate networks together. In this kind of VPN, there is no distinction at all between “client” and “server”; the two peers are equal, and either one can initiate the connection. See Fig. 21.

Fig. 21 A site-to-site VPN.#

The two VPN peers do not have a direct physical connection between them, but they can reach each other via the Internet. When the peer on the left wants to send a packet to a machine with a 10.100.x.x IP address, it encrypts the packet and sends it as the payload of another packet, to the public IP address of the peer on the right, via the Internet. The peer on the right will decrypt the packet and deliver it to its real destination on its local network.

Internet Key Exchange#

IKE performs two main tasks: authentication and parameter negotiation.

There are two versions of IKE in common use: IKEv1, and IKEv2. IKEv2 should be used for all new applications, since it is faster, more reliable, and more secure. IKEv1 should not be used anymore, but plenty of older VPNs still use it.

IKEv2 has several ways of performing authentication, but two of them are by far the most common: pre-shared key (PSK), and certificates.

PSK authentication is simple: both peers must have the same secret key (which they have previously agreed on through some external means), and they verify that they have the same key by exchanging hashes of the keys plus some other data. PSK authentication is generally only used for site-to-site VPNs, where there are only two peers. In hub-and-spoke VPNs, using PSK authentication would not give the hub any way to distinguish between the various users, and it would allow any spoke to impersonate the hub.

It’s important to note that the PSK is not used to encrypt anything, or to derive other keys; it is only used for authentication. This preserves forward secrecy.

It is critical that the PSK be generated randomly, like a cryptographic key, since it can be easily brute-forced by an attacker who can record the IKEv2 exchange — checking each guess only requires one run of a hash function. Unfortunately, in real-world deployments, PSKs are often just passwords, and not even good passwords at that. (I’ve seen this with my own eyes.) Don’t make this mistake!

Certificate authentication is similar to TLS. Each peer sends a certificate chain to the other. Each peer then verifies the chain it received, checking signatures and validity periods, and making sure that the chain leads to a CA certificate the peer trusts. Certificate authentication is most common for hub-and-spoke VPNs, since each user can get their own certificate, allowing the VPN server to distinguish them. Whoever administers the hub will also run a private CA for this purpose.

Along with authentication, peers using IKE will agree on a security association. The important elements of this are:

A symmetric cipher, for encrypting traffic, and a key size if necessary.

A hash function, for deriving keys from Diffie-Hellman output, and for authenticating traffic if the cipher is not AEAD.

Diffie-Hellman parameters. This is often given as a “DH group”, which is a single number referring to a predefined set of parameters[dhg]. There are group numbers for both classic and elliptic-curve DH. For example, “group 14” means classic DH with a specific 2048-bit prime. “Group 31” refers to ECDH using Curve25519.

An SA lifetime. After this amount of time has passed since the SA’s creation, it will no longer be considered valid, and the peers will need to run IKEv2 again. Common lifetimes are 4 to 24 hours.

The peer that initiates the connection presents a list of proposals for parameters, and the other peer chooses one.

Administrators of VPN peers have to decide on a list of proposals that the peer will offer and accept. In site-to-site VPNs, the administrators of the two peers usually agree on a single set of parameters manually3Most often by sending a document back and forth via email., and configure their VPN software or hardware to only propose and accept those parameters.

Once parameters are agreed on, the peers will run Diffie-Hellman to generate a shared secret, and then derive symmetric keys from it, thus creating an SA. This SA is then used as a secure channel to negotiate an additional SA, which will be handed off to the ESP implementation.

IKEv1 and Phases#

IKEv1, the older version of IKE, is still somewhat widespread. There are some notable differences between it and IKEv2, which administrators need to know about. (This is unlike TLS 1.2 and 1.3: in that case, the differences between the versions aren’t relevant to someone operating a TLS server.)

The process of negotiating parameters was significantly simplified in IKEv2. In IKEv1, the negotiation requires more roundtrips, and is divided into two distinct phases: Phase 1 (negotiating the SA for IKE) and Phase 2 (negotiating the SA for ESP). Even though IKEv2 does not have “phases” in the same way, a lot of writing about IPsec confusingly refers to IKE as “Phase 1” and ESP as “Phase 2”.

Another important difference between the IKE versions is that IKEv1 had a distinction between main mode and aggressive mode. Aggressive mode entailed a handshake that took fewer roundtrips, but transmitted the identities of the peers (i.e. their certificates) unencrypted. Main mode, by contrast, delayed exchanging certificates until after symmetric keys were agreed on, and thus was more protective of privacy. IKEv2 does not have this distinction, and always transmits peer identities encrypted.

To reiterate: if at all possible, only use IKEv2.

Encapsulating Security Payload#

ESP is the protocol that actually carries the network traffic of a VPN.

ESP takes in a security association from an IKE implementation. This SA can have different parameters from the SA that IKE uses for itself. It can have different algorithms, and, most notably, a different lifetime. ESP SAs have shorter lifetimes than the IKE SAs they come from: usually not more than 8 hours.

The most important fact about ESP’s cryptography, for an administrator, is that forward secrecy is optional. ESP must be specifically configured to have forward secrecy; in VPN hardware and software configuration, this means choosing a Diffie-Hellman group for ESP. With forward secrecy, Diffie-Hellman will be run each time an ESP SA is created. Without forward secrecy, instead of using DH to create new keys, new keys will be derived from the IKE SA’s shared secret. Therefore, in this context, forward secrecy means that if the IKE SA’s shared secret is compromised, the keys from any ESP SA that was created under it are not compromised. There’s no good reason not to configure ESP with forward secrecy.

All ESP traffic is encrypted and authenticated. Like TLS, ESP messages include sequence numbers as a defense against replay attacks.

Authentication Headers#

Authentication Headers (AH) is a protocol that can be used as an alternative to ESP. It does not provide confidentiality; only integrity and authentication. We’re only mentioning it here in case, for example, you need to choose between ESP and AH when setting up a VPN. There’s no real reason to use AH, in practice.

Key Takeaways#

TLS is the protocol that secures web traffic. It uses certificates for authentication, and provides confidentiality, integrity, and authentication of data.

A TLS connection is initiated by an exchange of messages called a handshake. The participants will agree on a cipher suite (a set of algorithms to use), do authentication, and agree on a shared secret from which to derive keys.

TLS 1.3 is the newest version, but 1.2 is currently the most widely deployed. Both are OK to use; anything older is not.

A major class of TLS vulnerabilities is downgrade attacks. In a downgrade attack, a man-in-the-middle interferes with a TLS handshake to cause the participants to use a less secure configuration. This is a result of TLS’ emphasis on backward compatibility.

IPsec is a set of protocols for creating virtual private networks. It is enormously complex, and as a result, a lot of the documentation about it is terrible.

IPsec’s main component protocols are IKE (which authenticates the peers, and sets up the algorithms and key material) and ESP (which actually carries the VPN’s traffic). The bundle of key material plus algorithm choices is called a security association (SA).

Authentication of peers in an IPsec VPN is usually done by means of either a pre-shared key (PSK; a secret value that both peers must have) or certificates.

The selection of algorithms and parameters (like SA lifetime) is negotiated between peers during IKE. For a VPN that is only going to have two peers, the algorithms and parameters are usually agreed on offline, by the administrators, and the VPN hardware or software is configured to only use those.

IKE creates two separate SAs: one for itself, and one to be handed off to an ESP implementation.

There are two versions of IKE; only IKEv2 should be used if at all possible.

ESP can optionally have forward secrecy. There’s no good reason not to configure it with forward secrecy.

AH is an alternative to ESP, and there’s no good reason to use it.