Blockchains and Cryptocurrency#

Blockchains and cryptocurrencies have exploded into mainstream consciousness in the past year, and the Internet is awash in poor explanations of them. We’ll be covering the cryptographic primitives that comprise them, and the protocols that allow many participants to use them cooperatively. We won’t cover everything in minute detail, in part because the technology is still evolving rapidly.

This reading is strictly focused on the technical aspects. It won’t cover anything about the economic and social systems that have been built up around blockchains. Those topics are important to understand, but beyond the scope of this course.

What Is a Blockchain?#

A blockchain is a type of data structure. It is a set of blocks, each of which is a chunk of data that contains at least these two things:

A payload. Depending on the specific blockchain protocol being used, the payload could be arbitrary bytes, or it could be structured in some way. In any case, the payload constitutes the data that is stored on the blockchain.

A cryptographic hash of a previous block. The input to the hash function is the entirety of the previous block — including its hash of a previous block. In casual parlance, people often say that a block “points to” a previous block, by means of this hash.

The latter is where the “chain” part comes from: the hashes link blocks together. From any given block, it’s possible to follow the links backward, along a chain of other blocks, until you reach the first block in the chain (which is the only one that contains no previous-block hash).

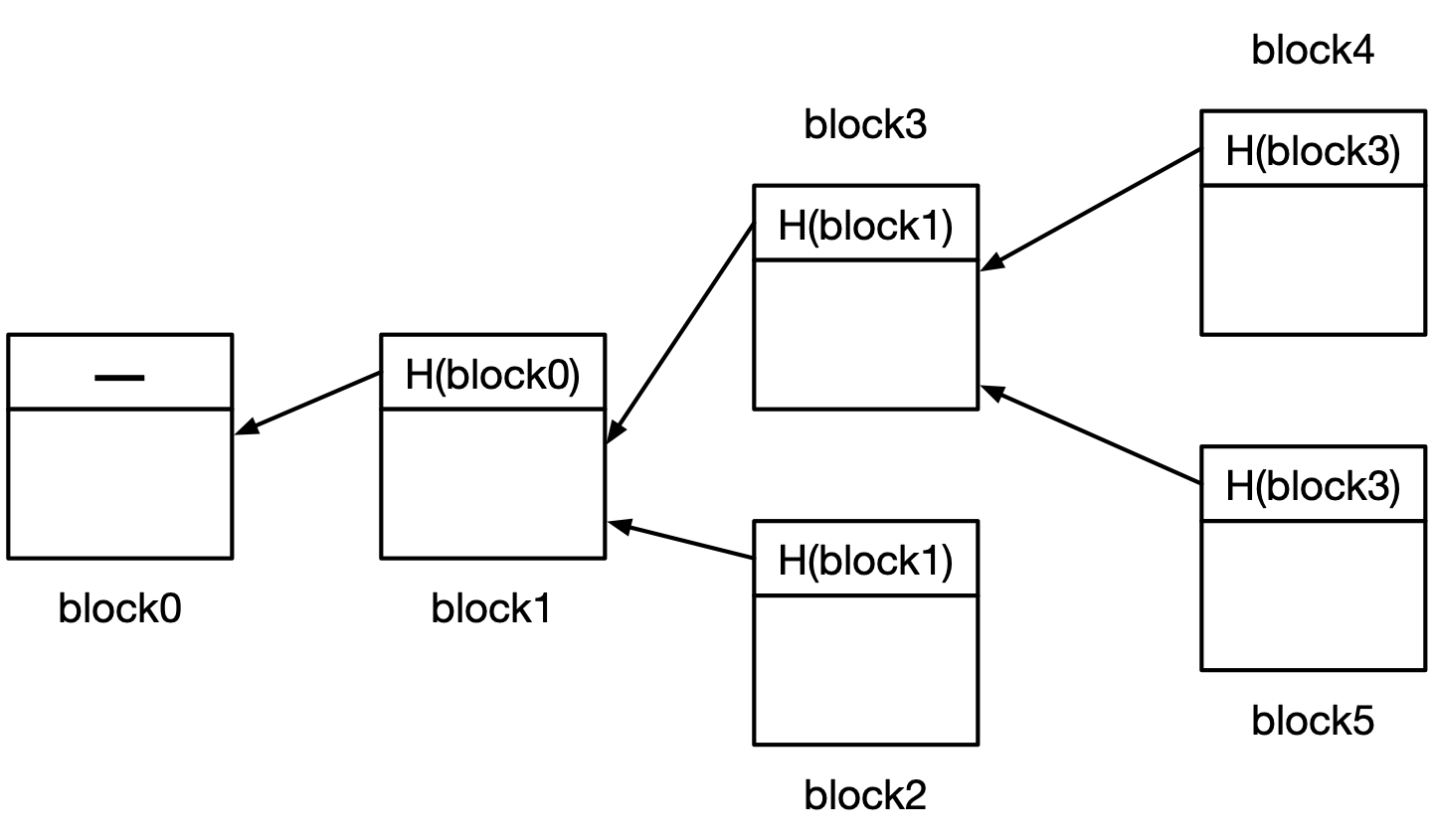

It’s important to note that, in this basic definition of a blockchain, the chain is not necessarily a single straight line. There is no reason why there can’t be multiple blocks that have the same previous-block hash, creating multiple parallel lines of blocks. Each parallel line is called a fork. See Fig. 22.

Fig. 22 A diagram of a blockchain.#

block0 is the first one, and has no previous-block hash. Multiple blocks have the hash of block1 as their previous-block hash, creating a fork. There is another fork based on block3.

A blockchain with forks doesn’t necessarily specify which fork is “official” or “authoritative”. That may be left up to the users of the chain to decide through some external means, or there may not be an “authoritative” fork at all.

The hash of any block depends on the contents of all the blocks that come before it in the chain of hashes. The integrity of the entire chain can be verified by looking at each block and making sure that its previous-block hash is indeed the hash of some other block in the chain. If a block’s contents are modified, without changing any blocks that point to that block, the chain will become invalid: any blocks that pointed to the modified block will now have a hash that doesn’t match any block in the chain.

As a Datastore#

The property that a block’s hash depends on the contents of all the blocks that come before it in the chain means that the most natural way to use a blockchain is as an append-only datastore.

We’ve seen that modifying an existing block makes the chain invalid. The chain can only be made valid again by updating all the previous-block hashes that come after the modified block. The only operation that can be done without changing the hashes of any existing blocks is to add a new block; i.e. to append to the datastore.

Note that it is not impossible to modify existing blocks in a blockchain. It is impossible1Unless the cryptographic hash function is catastrophically broken. to do so without making it obvious that there has been a modification. That’s the important thing.

That property is not particularly useful if there is only one entity (e.g. one server, or several servers under unified control) reading and writing to a blockchain. If that single entity wants to modify something in the middle of the blockchain, it doesn’t matter whether or not it’s obvious that has happened: there is no one else for that fact to be obvious to.

Therefore, blockchains are primarily useful for cases when multiple entities are reading and writing, without closely cooperating with each other. In such a situation, blockchains are a distributed datastore. Each entity that reads and writes the chain keeps its own copy, and they have some protocol for sharing their new blocks with each other. When one entity receives new blocks from another, they can easily validate the new blocks by computing hashes.

If you’re familiar with the version-control system Git, you may have noticed that Git fits this description exactly. Each commit in a Git repository is identified by the SHA-1 hash of its contents, and contains the hash of the commit before it2Git commits can actually have multiple “previous commits”, but we’ll ignore that here.. It is designed for many users to be able to add commits independently of each other. Forked history is a common part of many Git workflows (although in Git terminology, forks are called “branches”, and “fork” means something else).

Consensus#

So far, what we’ve seen of blockchains does not answer two important questions:

Who is allowed to write to the chain?

If there are multiple forks, which one is “official”, if any?

The question of who is allowed to modify a datastore is important for any type of datastore. Traditional databases have access control systems — often somewhat complex ones — that dictate who is allowed to read and write data. The version-control software Git explicitly does not answer these questions: determining who is allowed to write, and which fork is official, is left up to the users.

Blockchains are often meant to be publicly readable; that is, to have no restrictions on who can read from them. However, in order to be at all useful, there must be some restriction on who can write to them; otherwise, they’d quickly become full of garbage. But if a blockchain is distributed — stored and maintained by many independent entities, who do not necessarily trust each other to act honestly — who is in charge of enforcing these restrictions?

Here we’ll begin to talk specifically about Bitcoin, which introduced a novel solution to this problem called proof-of-work consensus. The idea behind this is to force anyone who wants to write to the blockchain to do a lot of work: an enormous amount of computation. This imposes real costs on writers: they must spend money to pay for computing hardware to do the computation, for space to put the hardware in, and for electricity to power and cool it.

This is done using cryptography. Each block on the Bitcoin chain contains a nonce, which has no inherent meaning. A block is not considered valid unless the block’s SHA-256 hash begins with a specific number of zero bits — currently, around 77. A block’s contents without the nonce are vanishingly unlikely to hash to something that starts with 77 zero bits. Therefore, entities trying to create a valid block must try an enormous number of possible nonce values, in order to find one that makes the block’s hash start with 77 zero bits. In Bitcoin, this process of hashing blocks with different nonces is called mining. When you hear about Bitcoin mining, this is what it means: just computing tons and tons of SHA-256 hashes.

I say the target number of zero bits is “currently” 77 because it goes up over time. The goal is to have valid blocks found at roughly a constant rate: one every ten minutes. However, the amount of computing power devoted to mining is constantly changing. To adjust for that, the target number of zero bits is calculated based on how long it has taken to find the most recent few blocks.

Conflicts#

It is possible for multiple miners to find different valid blocks at the same time. Such forks happen somewhat often, and are usually quickly resolved. When they happen, there will be some miners trying to find the next valid block on top of each of them. Whichever block gets a new block on top of it first is considered to be part of the authoritative chain — the general rule in Bitcoin is that the longest potential chain is the authoritative one.

The “longest chain” rule is what prevents existing blocks from being modified. It is possible to find a valid Bitcoin block whose previous-block hash refers to some old block. However, no other Bitcoin participants would accept it, because it would form a much shorter chain than the one that currently exists as the authoritative chain.

However, finding an alternative chain starting from a very recent block is a much more likely possibility, especially for an attacker with large amounts of computing power. This is the basis of a possible attack called a 51% attack, so named because an attacker who controlled 51% of the total mining power on the network would likely be able to execute it. If you controlled that much mining power, your mining would outpace everyone else’s. You could find, say, a chain of three blocks that branched off from the authoritative chain two blocks ago, before the rest of the miners could find a new block on the authoritative chain. You could publish that three-block chain, and other participants would have to accept it as authoritative, since it would be the longest chain. The two most recent blocks on the old authoritative chain would no longer be authoritative, which could cause serious problems. In Bitcoin, blocks record financial transactions, and real-world consequences result from completed financial transactions. Switching to a new authoritative chain, as in a 51% attack, would mean that some transactions previously considered final would now be gone, as if they never happened.

There is another type of fork called a hard fork. They are usually intentional and permanent, and result from disagreements among blockchain participants about the basic parameters of the blockchain. Bitcoin itself has several hard forks; one major fork is called Bitcoin Cash. It was created because of a disagreement among some Bitcoin developers about how to increase the capacity of the network. Only a subset of the developers wanted to make a certain change3The change had to do with the maximum size of blocks. As Bitcoin was being used for more transactions, this was becoming a problem: the low maximum number of transactions per block, and the mining rate of one block every ten minutes, meant Bitcoin’s total capacity was quite limited., and miners that went along with this change would be unable to interoperate with miners that didn’t. The Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash blockchains have a shared history up until August 2017; since then, they have been separate.

Other hard forks have been made to intentionally erase history. The most famous example is the Ethereum blockchain’s hard fork that undid the effects of a major attack, in which attackers stole a large amount of tokens. There are now the Ethereum chain, which doesn’t contain the effects of the hack, and the Ethereum Classic chain, which does. This is a good demonstration of the fact that it’s not impossible to modify an existing blockchain: it is possible if enough participants agree to abide by the modifications. There is a set of people in control of the network, contrary to the narrative that “code is law” and anything that happens on the blockchain is absolutely immutable.

Mining#

The reason why it makes sense for anyone to pay the huge costs of mining is an additional feature of Bitcoin: when you find a valid block, you earn a reward, which is recorded in the block itself. That reward additionally serves to keep writers honest. You’re compensated for mining by way of a record on the blockchain. That means that you’re invested in the integrity of the chain: if you put garbage onto the chain, the chain as a whole is less trustworthy as a datastore, which reduces the value of your reward.

This is why the participants in a proof-of-work consensus blockchain do not need to have an existing trust relationship (and why the mechanism is called “trustless”): if you’re not going to be honest, it simply doesn’t make economic sense to participate, so anyone who participates is probably being honest.

The costs and rewards of mining are also the reason why mining malware exists. If you can put mining malware onto other people’s computers, you can get the benefit of the mining without paying for the computing power to do it.

In the early days of Bitcoin, it was common for regular people to run mining software on their normal everyday computers. Nowadays, that’s extremely unlikely to be worthwhile: you would almost certainly pay more for electricity than you would earn from mining. Most mining is now done using purpose-built hardware, located in datacenter-like facilities, in places where cheap electricity is available.

Virtually all mining is now done as part of a mining pool. Any individual miner is vanishingly unlikely to ever find a valid block. However, finding a valid block is lucrative: now, the mining reward is 6.25 BTC, which is, in late 2023, over $230,000. (I am being vague because the USD-BTC exchange rate is extremely volatile.) To smooth out the rewards of mining, groups of miners will join together in mining pools. When one miner in the pool finds a block, all miners in the pool receive payouts from that block’s reward, in proportion to the amount of work they did. Currently, two large mining pools (AntPool and Foundry USA) collectively find over 50% of all Bitcoin blocks.

Proof-of-Stake#

Proof-of-work consensus is extremely energy-intensive: the whole point of it is to force participants to do huge amounts of computation. It is also wasteful, because the vast majority of the results of those computations are simply discarded.

This is a major problem with proof-of-work consensus, so more recently, an alternative mechanism called proof-of-stake has been developed. In proof-of-stake, participants must have a certain amount of the blockchain’s token (its unit of account; more on this later) in order to be allowed to add a block. While this is significantly less energy-intensive than proof-of-work, it leads fairly directly to centralization: participants with greater holdings are more likely to add blocks, and thus earn rewards and increase their holdings further.

Many popular blockchains are proof-of-work, including Bitcoin. Ethereum was originally proof-of-work, then switched to proof-of-stake in 2022. (Ethereum Classic still uses proof-of-work.)

Cryptocurrency#

One of the only applications for a trustless, distributed, append-only datastore is a financial ledger. A ledger is a list of financial transactions: each entry in the list records something of value moving from one account to another. Ledgers are an ancient concept — finance has rested on them since the invention of finance itself — but the development of the trustless-consensus blockchain allowed, for the first time, the creation of a ledger that could be maintained by multiple parties with no trust relationship.

We’ll start by covering Bitcoin, the first major application of a distributed-consensus blockchain to a financial ledger. It is also relatively simple to understand. Later developments, like smart contracts, arise from generalizing the way Bitcoin works. Some of the details in this explanation are simplified, but conceptually correct.

Wallets#

The central concept in Bitcoin’s implementation of a ledger is the wallet,

which is simply an ECDSA keypair. (Bitcoin uses the named curve secp256k1.)

When a person or business gives their “Bitcoin address” or “wallet address”,

that’s an ECDSA public key.

The Bitcoin ledger records transactions. These transactions contain numerical amounts, which are considered to be amounts of a unit called “bitcoin”. For clarity, from now on we’ll refer to the unit of account as “BTC” and the blockchain itself as “Bitcoin”.

The Bitcoin ledger does not record information in the form “Wallet A contains a total of \(x\) BTC”. It only records amounts moving from wallets to other wallets. It is possible to reconstruct how much BTC a given wallet contains by scanning all transactions and totaling how much the wallet has received and spent.

Each transaction has many inputs and many outputs. Outputs are the simplest to understand: they consist of an amount and a destination wallet address (a public key). The destination wallet can now spend the amount of BTC it was allocated in that transaction output.

Each input to a transaction is the output of another transaction, along with an ECDSA signature made with the private key of the wallet specified in that output. This is the basis of “possession” of BTC. Having the private key for a wallet allows a user to spend BTC that have been credited to that wallet.

The sum of all inputs to a transaction must be equal to the sum of all outputs of the transaction, plus a transaction fee. (As an incentive to miners, every transaction in a block specifies a fee amount, which is credited to the block’s miner.)

There is another type of possible input to a transaction: mining rewards. When a new valid block is found (“mined”), the miner puts a wallet address of its own in the block, and that address is thus credited with the reward for mining the block. That is how new BTC are created. The amounts of mining rewards are determined by a formula; the amount decreases over time, and will eventually reach zero after a total of 21 million BTC has been mined (around the year 2140).

Key Management#

Since control of BTC is determined by control of ECDSA private keys, key management is naturally a major concern for Bitcoin users.

The main choice that users must make about key management is whether to hold on to their private keys themselves. If a user chooses to do so, they are fully responsible for making sure that their keys are secure from attackers, as well as for making sure that the keys are safe from data loss. These are hugely consequential responsibilities! If you lose the private key to a wallet, all BTC in that wallet is lost forever. If an attacker gets the private key to your wallet, they can take all the BTC in the wallet and there is no way for you to get it back.

Losing wallet keys is a fundamentally different situation from something like forgetting your online banking password, or losing your debit card. In those cases, there are ways for humans to intercede and help you regain control of your account. Losing wallet keys is an unrecoverable situation: your only option would be to break ECDSA.

In a way, this is by design: part of Bitcoin’s aim is to enable financial transactions that don’t require a trusted third party, like a bank. Money in a bank account can be frozen or seized by authorities, and is tied to the account holder’s real identity. By contrast, since all that’s needed to transact BTC is wallet keys, it cannot be frozen or seized by authorities, and need not be tied to a true identity. If there were some way for an external party to help you recover from losing your wallet keys, that external party could also freeze or seize your BTC.

The practices necessary for keeping wallet keys secure are beyond the knowledge of all but the most tech-savvy users. Even for advanced users, those practices are inconvenient4For example, the recommended practice is to keep most of your BTC holdings in a so-called cold wallet. A cold wallet is one whose private key is kept on a device that is not connected to the Internet. That makes it much safer, but much less convenient to use.. Therefore, there are many services that offer custodial wallets: they hold the wallet’s private key for you and take on the task of keeping it secure and backed up. They offer a user experience similar to that of a traditional bank account. Importantly, the safety of your money is not: the custodial wallet service has full control over your holdings, and generally is not subject to anything like the rigorous regulations of the traditional banking industry. And if the custodial wallet service loses your key to data loss or an attacker, your wallet is gone.

As an illustration of how critical key management is, a substantial amount of BTC — roughly 10% of the total amount mined so far — is effectively gone, because the keys necessary to spend it are destroyed or inaccessible.

Anonymity and Privacy#

An often-touted benefit of Bitcoin is privacy. Transactions are made among wallets, which are just cryptographic keys; the wallet addresses themselves have nothing to do with the true identities of the people who control them. This is supposed to offer a level of privacy equivalent to physical cash.

However, it’s important to remember that Bitcoin is a public blockchain. Every single Bitcoin transaction that has ever happened is visible to the entire world. Although the addresses involved in the transactions are meaningless, it turns out that by examining patterns of transactions, based on addresses that are known to correspond to real-world entities, it’s possible to unmask the real identities behind transactions to a surprising extent. This is the case even though anyone can make as many wallets as they like; if you wanted, you could make a new wallet for every transaction.

As time goes on, it is increasingly difficult to acquire any BTC at all without associating one’s real-world identity with the transaction. Most users acquire BTC through an exchange: a company that accepts traditional currencies in exchange for BTC, and vice versa. Since these companies deal in traditional currencies, they are covered by traditional financial regulations, and thus are required to collect a certain amount of identifying information about their customers5This information is often referred to as “KYC”, short for “know your customer”.. Buying BTC from an exchange creates a transaction between your wallet and one of the exchange’s wallets, and thus allows authorities to associate your wallet (and any other wallets your wallet later transacts with!) with your real identity.

The only truly anonymous way to acquire BTC is from mining rewards, which are likely to be net-negative for users who don’t have access to specialized mining hardware.

A final note on anonymity, regarding Bitcoin’s pseudonymous founder “Satoshi Nakamoto”. A lot of people have claimed to be Satoshi, but none of them have offered the only kind of proof that matters: making a signature that is verifiable with one of the public keys known to be Satoshi’s, such as one from the first-ever Bitcoin block. Any “I am Satoshi” claim that doesn’t have such a signature can be immediately dismissed. (It’s possible that the real Satoshi has lost or destroyed all their private keys, in which case no ironclad proof that they are Satoshi will ever be possible.)

Non-Fungible Tokens#

Traditional currencies like the US dollar are fungible: one dollar is the same as any other. If Alice gives Bob a $1 bill, and Bob gives Alice some other $1 bill, then for all practical purposes, nothing has changed. They each end up with the same amount of money as they started with. The fact that neither of them has the same physical bill as before doesn’t matter, because each bill represents exactly the same amount of value.

By contrast, the traditional example of a commonly-traded non-fungible asset is real estate. No two buildings or plots of land are exactly alike. A one-for-one swap of real estate, unlike a swap of $1 bills, can’t possibly leave things unchanged. The participants in the swap end up with holdings that are noticeably different from what they started with.

BTC is fungible, as are many other blockchain-based tokens. However, blockchains are not restricted to recording transactions in fungible units. Some chains support non-fungible tokens (NFTs): non-fungible pieces of data that can be moved around in blockchain transactions. An NFT’s history can easily be traced through all the transactions that move it, all the way back to the transaction that created it. In this way, they are unique.

The mainstream understanding of NFTs is that they are pieces of digital art. Strictly speaking, the vast majority of NFTs simply contain URLs, not the actual digital art; the art is hosted at the URL, on a traditional web server. This is because storing the art (in the form of a PNG image, or whatever) within the NFT itself, and thus on a blockchain, would be too expensive. Every byte that is written onto a blockchain incurs cost in the form of computing power needed to hash it, which is reflected in transaction fees that scale with data size.

Notably, this means that the art, hosted on the web server, can change or even disappear, at the whims of the web host. Since the actual data of the art is not on the blockchain, the data-integrity guarantees of the blockchain do not apply to it. Most NFTs don’t even contain a hash of the art, so it’s impossible to tell whether the web-hosted art is the same as it was when the NFT was transacted. It also means that there is nothing preventing the creation of multiple NFTs with the same URL.

Ownership of an NFT generally does not confer any rights in the art that the NFT points to: by default, the original artist retains copyright in the image. The NFT is mostly analogous to a receipt: it has no inherent value and only describes a transaction that has taken place.

Smart Contracts, DeFi, DAOs#

Remember that the contents of blockchains can be anything, not just lists of financial transactions. In particular, blockchains can contain programs. These programs are called smart contracts. They are executed by miners during mining. They can read data from elsewhere in the chain, and their outputs are recorded in blocks. The most popular blockchain that supports smart contracts is Ethereum, although there are many others.

The important points about smart contracts is that they can execute in response to things happening on the chain (e.g. tokens being sent to a certain address), and they can create transactions of their own. They are created and updated by on-chain transactions, and thus their code is as public and immutable as anything else on a blockchain.

Notably, this means that bugs in smart contract code are visible to all, and if they cause undesirable consequences, those are written to the blockchain and thus immutable. (Well, almost — witness the Ethereum / Ethereum Classic hard fork.)

Groups of smart contracts can be used together to create cryptocurrency versions of systems that resemble traditional financial instruments, like loans, securities, and insurance. Such systems are called decentralized finance (shortened to DeFi). They are generally not regulated like their traditional analogues, and can involve high risk for users.

Smart contracts can also be used to implement rules for more general purposes, such as the governance of an organization. This kind of system is called a decentralized autonomous organization, or DAO. Usually, DAOs issue tokens which confer voting rights on owners, and trade the tokens for the hosting blockchain’s native token.

The programming language used for smart contracts depends on the specific blockchain. They are usually purpose-built programming languages, with features specific to the blockchain environment. The Ethereum blockchain uses a language called Solidity6Solidity is a poorly designed language, especially for the applications it’s meant for: its arithmetic operations are unintuitive and easy to make mistakes with.. The transaction fees for executing smart contracts (which Ethereum calls gas fees) are based on the amount of computation it took to execute the smart contract, which creates an unfortunate bias towards less robust code: more checks and error handling mean higher cost.

See Also#

The Crypto Story by Matt Levine is a long but light exploration of the financial and social significance of cryptocurrency. It’s neither boosterish nor overly skeptical, although I disagree with some parts of it. The author is a noted financial journalist, and speaks with authority on finance and economics. I recommend this to anyone who wants to know more about cryptocurrency’s effects on today’s world. (Don’t take his advice on password hashing, though.)

Key Takeaways#

A blockchain is a type of datastore that uses cryptographic hashes for data integrity. Its most natural use is as a distributed, append-only data store.

Proof-of-work consensus is a way by which multiple users can update the same blockchain, even if they do not necessarily trust each other. A newer alternative is proof-of-stake consensus. The current most popular blockchains use proof-of-work.

Proof-of-work is very energy-intensive, and is accomplished using a process called mining. Mining entails computing a hash function on a slightly changing input until the output matches a certain pattern.

Bitcoin is a proof-of-work blockchain that records financial transactions. The unit in which the transactions are denominated is called bitcoin, abbreviated BTC.

A Bitcoin wallet is an ECDSA keypair. Transactions credit BTC to the public key of a wallet. Transactions that spend BTC from a wallet are only valid if they come with an ECDSA signature made with the corresponding private key.

BTC, the unit of account, is fungible. The concept of a financial ledger concept can be generalized to record transactions in non-fungible units, which are called NFTs. An NFT is nothing more than a transaction recorded on a blockchain, and generally contains only a tiny amount of data. An NFT associated with a digital art piece, for example, only contains a URL to a traditional website where the art is actually hosted.

The ledger concept can be generalized further, to allow programs to be hosted on the blockchains. These programs can operate on on-chain data, run in response to on-chain events, and create new transactions. Such programs are called smart contracts.

Decentralized finance and decentralized autonomous organizations are applications of smart contracts.