Hash Functions#

Cryptographic hash functions are an extremely useful and versatile type of algorithm. Their primary use is to provide integrity. They can also be adapted and used within other algorithms to fulfill a wide variety of roles, all of which we’ll look at in this course.

They can be used to build a MAC, which can be used to provide authentication.

They can be used to derive cryptographic keys from other types of data[Kra10], including passwords, as we’ll see in a later chapter.

They can be used for random number generation, as we’ll see in a later chapter.

Their output can “stand in” for their input in certain ways, including as part of digital signature schemes, which we’ll see in a later chapter.

There are algorithms called “hash functions” that are not suitable for cryptographic use; they are used in data structures like hash tables. We aren’t covering those here; from now on, any time we use the phrase “hash function”, we mean the cryptographic kind only.

Overview#

A cryptographic hash function is an algorithm that has these properties:

It takes any number of bits as input, and produces a fixed number of bits as output.

It is deterministic: it always produces the same output for a given input.

However, the output should look like random garbage; it should have no discernible relationship to the input.

It should be infeasible to find two inputs that result in the same output. This is called collision resistance. A pair of inputs that result in the same output is called a collision.

It’s important to note that collisions are guaranteed to exist, for every hash function, simply because there are infinitely many possible inputs and finitely many possible outputs. Collision resistance means that finding collisions is infeasible, not impossible.

Given an output of the function, it should be infeasible to find an input that produces that output. This is called first preimage resistance.

Given an input \(m\), it should be infeasible to find a different input \(m'\) such that \(H(m) = H(m')\). This is called second preimage resistance. (Note that collision resistance implies second preimage resistance, because any second preimage \(m'\) would be a collision.)

Outputs display the avalanche effect, something we’ve already seen in the context of ciphers. Small changes in the input should result in large changes in the output. E.g. flipping one input bit should cause about half the output bits to flip.

Most writing on cryptography uses the word “hash” to refer to the output of a hash function. Some also uses “hash” to mean the functions too, but to avoid confusion, in this course we’ll refer to the functions as “hash functions”, and use “hash” to mean just the output. “Hash” can also be used as a verb, as in, “to hash some data,” meaning to input the data to a hash function.

Hash functions are sometimes called message digest algorithms, and their

outputs correspondingly called digests. In particular, Java’s cryptography

library uses this terminology: the class java.security.MessageDigest is the

library’s interface to hash functions.

Here’s a quick example. The hash of the phrase Hello World, using the

algorithm SHA-256, is:

a591a6d40bf420404a011733cfb7b190d62c65bf0bcda32b57b277d9ad9f146e

This is hexadecimal notation; hashes are almost always shown in hex. If we

change the phrase by flipping one bit, to Jello World, the resulting hash is:

19b10870e4d002a2407e9e1de15906199b625030cef24be8e9b3f4608827f83e

As you can see, it is very different. In fact, 128 out of the 256 bits are different: exactly half, a very good display of the avalanche effect.

Attacks#

Since hash functions don’t have plaintext, ciphertext, and keys, the attack models we use for ciphers don’t apply. Instead, we categorize attacks by what resistance property they target: collision attacks, first preimage attacks, and second preimage attacks. A collision attack aims to find a collision, and so on.

Like other types of cryptographic algorithm, all three of these attack types can be carried out by brute force:

A brute-force collision attack entails computing and storing hashes of many inputs, checking for a match among the stored hashes with every hash you compute. We’ll look into the mathematics of this in the next section.

A brute-force first or second preimage attack entails computing the hashes of many inputs, comparing against your target hash.

Hash functions can be subject to cryptanalytic attacks too. Like block ciphers, hash functions are supposed to obscure patterns in their input, but none of them are perfect; cryptanalysis can take advantage of such patterns.

Birthday Paradox#

How many people do you think you’d have to get in a room, so that the chances of two of them having the same birthday is over 50%?

Intuitively, you might guess something around 150 or 180: about half the number of possible birthdays. However, the true answer is 23. This is called the birthday paradox, not because it’s a true logical paradox, but because it’s just a surprising answer.

In general, if there are \(n\) people in the room, the probability that two of them share a birthday is (assuming there are \(B\) possible birthdays):

There is a good approximation to this, of which we won’t show the proof1For the curious, it’s based on the Taylor series approximation of \(e^x\).:

We can solve this for \(n\), to get a formula for the approximate answer to the high-level question: how many people do you have to get in a room so that the probability of two of them sharing a birthday is \(P\)?

For the particular case of \(P = 1/2\), this simplifies to:

Here is the relevance of all this to hash functions. Instead of considering the days of the year as possible birthdays, consider the \(2^b\) possible outputs of a \(b\)-bit hash function. How many hashes would you have to compute in order for the probability of finding a collision to be over 1/2? The above formula is the answer, around \(\sqrt{1.386 \cdot 2^b}\).

This means that for a hash function to make a brute-force collision attack take \(2^n\) steps to have a success probability of over 1/2, the function must have around \(2^{2n} / 1.386\) possible outputs; that is, its output must be of length \(2n - \log_2(1.386)\) bits. Generally this is simplified to just \(2n\).

Restated more concretely, if we want a hash function to require \(2^{128}\) steps for a brute-force collision attack to have a 1/2 chance of succeeding, it must have a 256-bit output. 256 bits is now considered the minimum acceptable hash length.

Hashing Passwords#

You may hear about hash functions being used to store passwords securely, such as in the context of a web application. It is true that hash functions are usually involved in storing passwords securely, but simply storing the hash of a password is not secure.

Similarly, because the output of hash functions are in just the right shape to be used as cryptographic keys (e.g. 256 bits of patternless nonsense), it’s a common mistake to hash a password in order to derive a cryptographic key from it. That is not secure either!

We’ll look at how to handle passwords securely in much more detail later in the course; there is an entire chapter devoted to it.

Caution

Do not just hash a password in order to derive a cryptographic key from it, or to try to store it securely. Doing so is not secure for either purpose.

Non-Cryptographic Uses#

Cryptographic hash functions are commonly used outside cryptographic contexts. As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, the hash of a chunk of data can stand in for the data itself. For example, a file-syncing application (like Dropbox or iCloud) can use hash functions to ensure that the client and server have the same contents of each file. The client can tell the server, “I have a file README.txt with the hash abcd1234.” The server can hash its version of README.txt and check whether the result matches what the client said. If so, the server knows it already has the same file contents as the client — if the contents weren’t the same, the hash would be different — and the client does not need to send the actual file contents to the server, thus saving time and bandwidth.

Hash functions are often used to detect accidental or random modification of data (as opposed to intentional). For example, if a large body of data is to be sent over a network, the sender can send a hash of the data alongside it. The receiver can hash the incoming data and compare the result against the hash sent by the sender. If they match, the receiver can be certain that the data they received does not have a random error. Something similar can be done with data that is stored on disk for a long time.

Note that that scheme does not detect intentional modification of the data! An attacker could modify the data and modify the hash to match. Detecting intentional modification requires introducing a secret; we will see how that’s done securely later in this chapter.

The popular distributed version-control software Git uses a hash function to create commit identifiers; a Git commit hash is (roughly speaking) the hash of the commit’s contents. A commit’s contents include the hashes of its parent commits, which ensures the integrity of the entire line of history leading back from any commit. (We will see this concept again in the course.)

The security research community often uses hashes as a form of “sealed envelope”. A security researcher who discovers a vulnerability will want to publicly claim credit for it, but not before giving the vendor of the vulnerable system a chance to publish a fix. They can use a hash to prove they knew the details of the vulnerability before the fix was published. Before notifying the vendor, they write up the details in a text file, hash the text file, and publish the hash. Others cannot learn anything about the contents of the file from the hash. After the vulnerability becomes public, the researcher can publish the text file, and others can verify that the hash of that file matches the previously published hash, to confirm that the researcher knew the vulnerability before it was published, and thus deserves credit for finding it.

SHA-2 (-224, -256, -384, -512)#

SHA-2 is a set of six closely related algorithms, published by the NSA in 2001, and standardized by NIST. These algorithms are very widely used, including in new applications, and there are currently no concerns about their security.

The six related algorithms are named for their output length in bits: SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, SHA-512/224, and SHA-512/256. The term “SHA-2” refers collectively to all the variants.

Really, there are only two different algorithms, SHA-256 and SHA-512, and they have the same overall structure. The rest are truncated versions of these two:

SHA-224 entails running SHA-256 and taking the leftmost 224 bits of the output.

SHA-384, SHA-512/224, and SHA-512/256 all entail running SHA-512 and taking the leftmost 384, 224, and 256 bits of the output, respectively.

The truncated versions are also initialized with different constants (see below), but are otherwise identical to their respective non-truncated versions. The only real use for these truncated versions is if you need a hash that fits in a specific number of bits; if length doesn’t matter, use either plain SHA-256 or SHA-512.

Modern Intel processors have hardware support for SHA-256, much like they do for AES, which means that no other hash function can match its performance on Intel hardware. That contributes to its lasting popularity.

All the SHA-2 variants use a common hash function structure called the Merkle-Damgård construction. The overall structure is:

Start with an internal state of the same size as the output, initialized to some constants.

Divide the input into blocks of a fixed size, applying padding to the final block as needed.

Input each block into a compression function, which mixes the block into the internal state.

The output of the algorithm is the internal state after all input has been processed.

All of the most popular hash functions before SHA-2 used the Merkle-Damgård construction. It has several notable weaknesses, which we’ll cover later in this section, after looking at the details of SHA-2. For now, we’ll look in detail at SHA-256 only, then talk about how SHA-512 differs later.

SHA-256 works in terms of words, which are 32-bit integers. Its internal state is eight words, which matches the output size of 256 bits. It divides the input into 512-bit blocks, and views those as 16 words. It uses the big-endian convention; it breaks up the 512-bit block into 32-bit groups, and considers the leftmost bit of each group to be the most-significant bit of that word.

Let’s call the internal state \(H_0\) through \(H_7\). They are initialized as follows:

These are nothing-up-my-sleeve numbers: they are based on the square roots of the first eight prime numbers.

Then, for each 16-word input block, do the following:

Expand the 16-word input block into 64 words, \(W_0\) through \(W_{63}\), as follows:

\[\begin{split} W_i = \begin{cases} M_i & 0 \leq i < 16 \\ \sigma_1(W_{i - 2}) + W_{i-7} + \sigma_0(W_{i-15}) + W_{i-16} & 16 \leq i < 64 \end{cases} \end{split}\]All the additions are modulo \(2^{32}\), and the two \(\sigma\) (sigma) functions are defined as follows:

\[\begin{split} \sigma_0(n) &= (n \ggg 7) \oplus (n \ggg 18) \oplus (n \gg 3) \\ \sigma_1(n) &= (n \ggg 17) \oplus (n \ggg 19) \oplus (n \gg 10) \end{split}\]Note that the last operation in each is a shift, not a rotation; it is a logical right shift, meaning the vacant bits on the left are filled with zeroes.

This has the effect of diffusing input bits throughout the expanded words. Each word after the first 16 depends on four previous words. The rotations and shifts in the sigma functions mean that each bit of an input word will affect many different bit positions of expanded words.

Initialize eight variables, which we’ll call \(a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h\); set these to the eight words of the internal state, \(H_0\) through \(H_7\), respectively. We will “compress” the block into these eight variables.

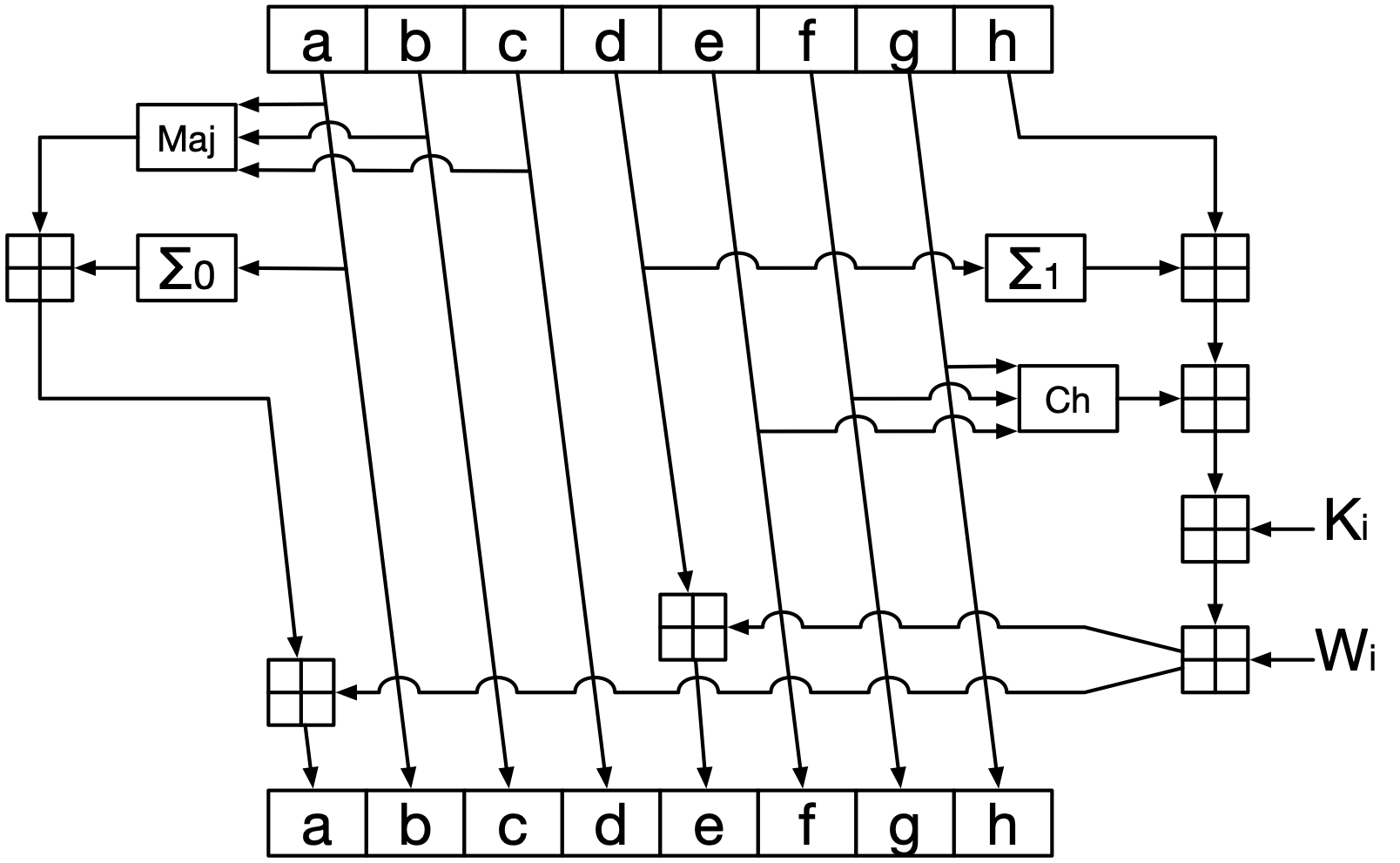

Do 64 rounds of the following compression function. Let \(i\) be the round number. The \(\boxplus\) symbol represents addition modulo \(2^{32}\).

\(K_i\) are round constants; there’s a different one for each round. We won’t list them here, but they’re nothing-up-my-sleeve numbers.

\(\texttt{Ch}\) is called the “choice” function, and it is defined as follows: \(\texttt{Ch}(e, f, g) = (e \land f) \oplus (\neg e \land g)\). The \(\land\) means bitwise AND, and \(\neg\) means bitwise NOT. In words, what this is doing is: for each bit position, use the corresponding bit of \(f\) if that bit of \(e\) is 1, otherwise use the corresponding bit of \(g\). It uses the bits of \(e\) to “choose” bits from \(f\) or \(g\).

\(\texttt{Maj}\) is the “majority” function, and it is defined as follows: \(\texttt{Maj}(a, b, c) = (a \land b) \oplus (b \land c) \oplus (a \land c)\). In words: in each bit position, use whichever value is more common in that position across the three inputs.

The \(\Sigma\) functions are defined as follows. Note that all operations are rotations this time; there are no plain shifts.

\[\begin{split} \Sigma_0(n) &= (n \ggg 2) \oplus (n \ggg 13) \oplus (n \ggg 22) \\ \Sigma_1(n) &= (n \ggg 6) \oplus (n \ggg 11) \oplus (n \ggg 25) \end{split}\]Set \(H_0 \leftarrow H_0 + a\), \(H_1 \leftarrow H_1 + b\), and so on. This mixes the compressed block into the internal state.

After all the blocks are processed as above, concatenate \(H_0\) through \(H_7\) in order, under the big-endian convention; this is the output hash.

SHA-224 is the same algorithm, except with different initial values of \(H_0\) etc., and with the output truncated to 224 bits; i.e. only \(H_0\) through \(H_6\) are concatenated to form the output.

SHA-512 has the same overall structure as SHA-256, but the details are tweaked. The differences are:

The word size is 64 bits. Additions are done modulo \(2^{64}\).

The block size is 1024 bits: sixteen 64-bit words.

The block is expanded to 80 words, instead of 64.

The initial values of \(H_0\) etc. are different. (Each of SHA-384, SHA-512, SHA-512/224, and SHA-512/256 have different initial values.)

The \(\sigma\) and \(\Sigma\) functions have different rotation and shift amounts.

There are 80 rounds of the compression function, instead of 64.

The round constants are different — there are 80 of them, and they are each 64 bits.

Padding#

The padding for SHA-256 and its truncated variant works as follows:

Append a single 1-bit to the input.

Append 0-bits to the input until the total length of the input is 64 bits short of the next multiple of 512. For example, if the original input is 600 bits long, step 1 would make it 601 bits long. Then the next multiple of 512 is 1024, so you would append \(1024-601 = 423\) 0-bits.

You might append nothing in this step, if adding the 1-bit in step 1 makes the total length 64 bits short of a multiple of 512. In practice, that is very unlikely, since inputs are essentially always whole numbers of bytes long.

Append the length of the original input in bits (pre-padding), expressed as a 64-bit-wide base-2 number.

The padding for SHA-512 and all of its truncated variants is similar. The differences are that the length appended in step 3 is 128 bits wide, and the input is padded up to a multiple of 1024 bits long.

Cryptanalysis#

To date, there have not been any significant cryptanalytic results against the full 64 rounds of SHA-256 or the full 80 rounds of SHA-512. The best results are practical collision attacks against fewer than half the rounds of either variant.

Length Extension Attacks#

In the case of SHA-256 and SHA-512, the fact that the output of the hash function is simply the entire internal state of the algorithm creates a weakness to a type of attack called length extension attacks.

If you have a hash \(H(m)\), you can compute \(H(m \concat \texttt{Pad}(m) \concat e)\), for any \(e\), without actually knowing \(m\). (\(\texttt{Pad}(m)\) denotes the bits appended to \(m\) as padding during the computation of \(H(m)\).) All you need to know is the hash of \(m\), and the length of \(m\).

This can be problematic if \(m\) is secret, or includes a secret. A system’s security may assume that an attacker without the secret can’t compute the hash of an input that includes the secret, and length extension attacks break that assumption.

To perform the attack, instead of initializing the algorithm’s internal state with the standard nothing-up-my-sleeve constants, you initialize it with \(H(m)\), then process \(e\) as normal.

Length extension is not a preimage attack or collision attack, since it doesn’t expose \(m\), and it doesn’t find another input \(m'\) such that \(H(m) = H(m')\). However, it can still result in dire consequences. People have attempted to turn Merkle-Damgård hash functions into MACs by simply hashing the MAC key followed by the message; this can be trivially exploited using length extension. People have made this mistake in the real world[DR09].

It is possible to build a MAC from a Merkle-Damgård hash function — see the HMAC section later in the chapter — but special care must be taken to foil length extension attacks.

It is notable that the truncated SHA-2 variants are not susceptible to length extension attacks, because their outputs are not the algorithm’s complete internal state. This isn’t really seen as an argument in their favor, though; you shouldn’t use one of the truncated variants as a way to avoid length extension attacks.

It’s important to be clear that SHA-256 and SHA-512’s vulnerability to length extension is not a cryptanalytic weakness. It is simply an easy way to misuse these algorithms. If they are used correctly, length extension is not an issue. The most important aspect of using them correctly entails using HMAC (in a later section) to include a secret in the input to the hash function.

Other Problems#

A related problem with the Merkle-Damgård construction is that if you find individual blocks that collide, you can combine them into an exponential number of colliding messages. This was first detailed by Antoine Joux in 2004.

Suppose you have a pair of blocks \((b, b')\) such that, starting from internal state \(H\), processing either \(b\) or \(b'\) results in the same internal state \(H'\). Suppose you also have a pair of blocks \((c, c')\) such that, starting from internal state \(H'\), processing either \(c\) or \(c'\) results in the same internal state \(H''\).

Then, from having found two pairs of colliding blocks, you actually now have four colliding messages: \(b \concat c\) and \(b \concat c'\) and \(b' \concat c\) and \(b' \concat c'\). Extending this further, if you have \(k\) pairs of chained collisions like this, you can choose either one from each pair, and thus form \(2^k\) colliding messages, called multicollisions.

The technique above is somewhat constrained: you must find single-block collisions, and the resulting multicollisions will all be of the same length. Expandable messages are a generalization that improves on those shortcomings. This technique was published by John Kelsey and Bruce Schneier in 2004[KS04]. It involves finding colliding pairs of messages of specific different lengths, so that you can piece together a message, of any length, which brings the algorithm to a target internal state.

There is still a further iteration of this technique, called a herding attack, published by John Kelsey and Tadayoshi Kohno in 2006. They also call this a “Nostradamus attack” because it can allow you to fake making seemingly-impossible predictions of the future that you’ve committed to using a hash (as in the Non-Cryptographic Uses section). It entails finding colliding pairs starting from initial states that are the final states of other colliding pairs. The attack allows you to find a suffix for a fixed message (e.g. your predictions of the future) that will result in a fixed final hash (e.g. the hash you’ve published to commit to your predictions).

To be clear, these techniques are not ways of finding a collision from scratch. Rather, they are ways of quickly turning a small number of collisions into a much larger number. An ideal hash function would not have this property: finding one collision would be of no use in finding more collisions.

All of the above problems were a strong impetus for finding a different way to build hash functions. We’ll see the result in the next section.

SHA-3#

The current state of the art in hash functions is SHA-3[sha15]. Like AES, SHA-3 was the winner of a NIST-administered public competition, held from 2008 to 2012. Before being chosen as the winner, the set of related algorithms that became SHA-3 was known as Keccak (pronounced “ketch-ack”). Both SHA-3 and SHA-2 are recommended for use in new applications. Over time, SHA-3 may come to be clearly preferred over SHA-2, but we’re a long way from that: SHA-2 is still essentially the default choice of hash function.

There are six NIST-standardized variants of SHA-3: SHA3-224, SHA3-256, SHA3-384, SHA3-512, SHAKE128(\(d\)), and SHAKE256(\(d\)). They are all based on the same core algorithm, and differ mainly in their output lengths. The first four variants (SHA3-224, etc.) are named for their output lengths in bits. The final two, SHAKE128(\(d\)) and SHAKE256(\(d\)), have variable-length output of \(d\) bits.

The shared core algorithm is called the sponge construction. It maintains a 1600-bit internal state, and consists of an “absorbing” phase in which input blocks are XORed into parts of the internal state and the state is then permuted, and a “squeezing” phase where parts of the internal state are taken as output and the state is then permuted.

Each variant of SHA-3 is described by several quantities:

\(d\), the output length in bits.

\(c\), the capacity, in bits. For the fixed-output-length variants, the capacity is \(2d\). For the SHAKE variants with variable output length, the capacities are 256 bits (for SHAKE128) and 512 bits (for SHAKE256).

The significance of the capacity is that it describes how much of the internal state is not involved in each absorbing or squeezing action. While absorbing, \(c\) bits of the state are left unchanged as input bits are XORed into the rest of the state. While squeezing, \(c\) bits of the state are not used as part of the output.

\(r\), the rate, is \(1600 - c\). It describes how much of the internal state is involved in each absorbing or squeezing action. While absorbing, \(r\) bits of input are XORed into the state between permutations. While squeezing, at most \(r\) bits of the state are added to the output between permutations.

In this way, it is also the hash function’s block size, in that the function processes the input in \(r\)-bit chunks. The input will be padded so that its length in bits is a multiple of \(r\).

A domain separation suffix, which is a few bits that are appended to the input before padding. For the fixed-output-length variants, the suffix is the bits

01. For the variable-length SHAKE variants, it is1111.This is so that fixed-length variants do not have the same output as variable-length variants for the same input. E.g., the output of SHA3-256 is not the same as the output of SHAKE256(256), even though they have the same output length, capacity, and rate.

The 1600-bit size of the internal state is the same for all variants.

Sponge Construction#

The overall flow of the sponge construction is simple:

Pad the input so that its length in bits is a multiple of \(r\).

Initialize the internal state to all zero bits.

For each \(r\)-bit block of input:

XOR the block of input into the first \(r\) bits of the state.

Run the permutation function on the state (see the next section).

Set the output, \(Z\), to an empty bit string.

Do the following until the length of \(Z\) is at least \(d\) bits:

Append the first \(r\) bits of the state to \(Z\).

Run the permutation function on the state.

Truncate \(Z\) to \(d\) bits. \(Z\) is the algorithm’s output.

Permutation Function#

The 1600-bit array of internal state is, in principle, a three-dimensional array of bits: \(5 \times 5 \times 64\). In practice, it is implemented as a two-dimensional, \(5 \times 5\) array of 64-bit integers. We’ll use the latter representation in this section.

In between absorbing input and squeezing output, the internal state is

permuted. SHA-3 does this using five different step mappings, which are

called theta, rho, pi, chi, and

iota. We won’t look at their exact details here, but only get an

intuition for what they do.

thetafirst computes a temporary array of five 64-bit integers; each one is the XOR of all the elements of one column in the state array. Then it XORs each 64-bit integer in the state array with the temporary array’s value for the column to the left, and then with the temporary array’s value for the column to the right, bitwise left-rotated by 1.rhodoes a bitwise rotation of each 64-bit integer, by an amount that depends on its position within the \(5\times 5\) array.pirearranges the 64-bit integers within the array, without modifying them.chiXORs each row in the array with a nonlinear function of two other rows. This is the only nonlinear part of the permutation function. (The function involves bitwise AND, which makes it nonlinear.)iotaXORs each 64-bit integer with a 64-bit round constant. The round constants are mostly 0-bits, with at most five 1-bits. In principle, they are generated by a simple function, but in practice, implementations hardcode them.

The permutation function consists of 24 rounds. Each round consists of all five step mappings, executed in the order above.

Thinking of the state as a three-dimensional array again, you can see how each of the five step mappings mixes bits across one or two of those dimensions, thus achieving diffusion:

thetamixes adjacent columns.rhomoves bits along the long axis.pimoves each bit to a different row and column, so that they have different neighbors for thethetaandchimappings.chimixes adjacent rows.Finally,

iotasimply flips a few of the bits.

Padding#

SHA-3 padding is very simple. For a variant with rate \(r\):

Append the domain separation suffix to the input.

Append a single 1-bit to the input.

Append 0-bits until the total bit length of the input is one bit short of a multiple of \(r\). (This may mean appending nothing.)

Append a single 1-bit.

This scheme is often referred to as pad10*1.

Security#

There are, as yet, no significant cryptanalytic results against SHA-3. The only known better-than-brute-force attacks are against reduced-round variants, and require infeasible amounts of time and memory.

SHA-3 is still relatively new, though, so there will likely be some progress in the coming years. It seems very unlikely, though, that there will be any cryptanalytic attack that breaks SHA-3 for practical purposes.

All SHA-3 variants are safe from length extension, because their outputs are not the entire internal state of the algorithm.

SHA-1 and MD5#

Caution

Do not use either of these algorithms in new applications! We have to mention them because they are still very widely used, despite being known to be insecure: their outputs are too short, and actual collisions have been found for both.

Both of these hash functions use the Merkle-Damgård construction, meaning they are susceptible to length-extension, etc. There have been a lot of cryptanalytic attacks against both, so we’ll only summarize the attacks that have been carried out in practice.

SHA-1 was designed by the NSA, and published in 19952SHA stands for “Secure Hash Algorithm”. SHA-1 is a very slight variation on an earlier NSA-designed algorithm called SHA-0, which they withdrew almost immediately after publication because it was insecure.. It produces a 160-bit output, which is less than currently considered ideal. Like SHA-256, there is hardware support for SHA-1 built into modern Intel and Apple processors. SHA-1 is the hash function used by Git for its commit hashes.

In 2017, a collision for SHA-1 was produced by a team from Google and Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica[S+17]. They called it “SHAttered”, in keeping with the modern practice of having catchy names for computer security exploits. Using Google’s infrastructure, they did roughly \(2^{63}\) SHA-1 evaluations to produce two distinct PDF files that have the same SHA-1 hash. The attack requires massive amounts of computing power, but it’s within the reach of government and large corporations like Google.

SHAttered demonstrates a particularly serious kind of collision attack: one

where the two colliding values are semantically similar. If you find a collision for the input Hello World, but the colliding input is a hundred gigabytes of patternless garbage, that’s bad but not particularly useful in practice. By contrast, SHAttered found colliding inputs that are both valid PDF files, of the exact same size, with almost

the exact same contents. There is some apparently-patternless garbage in the files to make the

collision happen, but it is not visible to a human viewing the files in a PDF

viewer. File formats like PDF that can contain non-visible data are particularly

susceptible to this kind of exploit.

MD5 produces a 128-bit output. Not only is that considered too short to be secure now, but MD5 has been comprehensively broken with cryptanalysis.

A 2009 attack by Alexander Sotirov et al. developed an attack that would have allowed them to produce a TLS certificate, for any website, that would have been accepted by web browsers at the time[S+09]. (We will cover the infrastructure of TLS certificates in detail in a later chapter.) Their attack takes about \(2^{49}\) steps: a lot, but definitely feasible, especially now, 13 years later.

In 2012, the authors of the Flame malware used the technique from the Sotirov attack to forge a Microsoft code-signing certificate by finding an MD5 collision with a genuine Microsoft certificate. They used it to sign their malware and thus make it look like non-malicious software.

The final nail in the coffin came in 2013, when Tao Xie, Fanbao Liu, and Dengguo Feng found a collision attack that can find a collision with \(2^{18}\) MD5 evaluations[XLF13]. That’s only 262,144: it could run on your computer in less than a second.

Given all that, MD5 should be replaced in all cryptographic usage as soon as possible.

HMAC#

Recall the definition of a message authentication code from the chapter on authenticated encryption. It may remind you of the definition of a hash function: both types of algorithm are concerned with detecting modifications to data, and both output a small, fixed-length chunk of data.

It is very important, though, not to confuse the two. The crucial difference is that hash functions, by themselves, do not provide authentication. They provide integrity only. Without a secret input, there can be no authentication.

HMAC, which stands for hash-based message authentication code, is a way of creating a MAC algorithm using any hash function. It is very commonly used in practice.

Note that when specifying which algorithms are being used in a system, saying only “HMAC” is not enough information. The hash function being used in HMAC must be specified too; you’ll often see this written as, for example, “HMAC-SHA256”.

HMAC is defined as follows, for a hash function \(H\), key \(K\), and message \(M\):

\(K'\) is defined as \(H(K)\) if \(K\) is longer than the hash function’s block size, or just \(K\) otherwise. Simply put, it’s a version of the key that is known to fit within a single block of the hash function.

outerpadis the same length as the hash function’s block size, and consists of repetitions of the byte0x5C.innerpadis the same length, and consists of repetitions of0x36.

HMAC is specifically designed to be secure even if \(H\) is vulnerable to length-extension attacks. A naïve scheme that computed a tag as simply \(H(K \concat M)\) would be easily forgeable if \(H\) were one of the many popular hash functions that is vulnerable to length-extension. That is the rationale for the double application of \(H\); the outer application hides the inner hash, which would be length-extendable.

Another naïve MAC scheme might be to avoid the length extension attack by computing \(H(M \concat K)\), but this has another problem. If there are two colliding messages \(M\) and \(M'\), then \(H(M \concat K)\) and \(H(M' \concat K)\) collide as well, making it possible to forge a tag for \(M\) using a tag for \(M'\). HMAC avoids this issue by prepending the key to the message.

Note

Collision resistance is required of hash functions, but it is not required of MACs in general. For example, it’s perfectly fine if Poly1305 produces equal tags using different keys. However, if HMAC produces equal tags under any circumstances, that is a problem, because it’s a collision in the underlying hash function.

Key Takeaways#

A hash function is a deterministic function that takes an arbitrary-length input and produces a fixed-length output. It should be infeasible to derive an input from an output (i.e. to invert the function), and it should be infeasible to find two inputs that produce the same output (i.e. a collision). Hash functions can be used to provide integrity.

The minimum output length for a secure hash function is 256 bits. This makes it so that finding a collision by brute force should require, on average, \(2^{128}\) hash computations.

SHA-3 is a modern, secure hash function. There are several variants, with different output lengths; the shortest is 256 bits. It is not yet the most widely adopted and implemented one, but it probably will become so over time. Any SHA-3 variant is a reasonable choice of hash function.

SHA-2 is a family of hash functions; the most common variants of it are called SHA-256 and SHA-512, with the numbers indicating their output lengths in bits. They are vulnerable to a simple attack called a length extension attack, which means you have to be careful in how you use them. They are still considered secure, and a reasonable choice of hash function.

SHA-1 and MD5 are still somewhat widely-used hash functions, but their output lengths are considered too short to be secure, and collisions have been found for both of them. MD5 in particular is completely broken by cryptanalysis.

HMAC is a way of using a hash function to construct a MAC. It is specifically designed to be secure even with a hash function that is vulnerable to length extension attacks. It is a reasonable choice of MAC.