Cryptography in Practice#

We’ve now spent a lot of time talking about algorithms and protocols in the abstract. Now it’s time to address how you can actually do this stuff. How do you do cryptographic operations on a computer?

In this chapter, we’ll focus on specific operations that you may have to do for a job. It is not likely, for example, that you’ll ever have to manually generate an AES key and IV etc.; that should be taken care of by whatever tool you’re using. It is likely, though, that you’ll have to generate a Certificate Signing Request. We’ll cover that, and more.

Unfortunately, a lot of the subject matter we’ll deal with here is complex — in many cases needlessly so, in ways that are just tedious and not intellectually interesting. We’ll avoid going too far into those details; the aim is to give you enough information to cover the most common cases, and to be comfortable looking up more information if you ever need to.

Data and File Formats#

In this section, we’ll go through the various representations of cryptographic data that you’ll encounter in real life.

Base64#

Cryptographic data — ciphertext, keys, signatures, etc. — consists of arbitrary bytes. However, sometimes it must be transmitted in mediums that expect to be transmitting text, like email and Word documents. The software that processes those, like email clients and word processors, may try to decode bytes of cryptographic data as if they are the output of some character encoding. However, that decoding might not be successful, and the software might end up dropping some parts of the data, or decoding it in such a way that character-encoding them again will result in different bytes. This is obviously a deal-breaker for cryptography: even a tiny change to a key or ciphertext will make operations on them fail or output nonsense.

One way to avoid this is to use hexadecimal notation. It only uses digits and the letters A through F, which are representable in any character encoding, and which any program can handle without mangling. However, hex notation is space-inefficient: every byte of data is represented as two characters.

The commonly-used alternative is called Base64. Base64 can represent a

sequence of arbitrary bytes using only the uppercase and lowercase Latin

letters, the decimal digits, and the characters + and /. That is a total of

64 different characters, all of which are representable in any character

encoding. The output of Base64 is longer than the input, but less so than hex

notation: Base64 turns every three bytes of input into four bytes of output.

In some contexts, however, the characters + and / have special meanings; for

example, in URLs and file names. For those situations, there are some variants

of Base64 that use other characters instead of + and /: most notably, the

“URL-safe” variant which uses the characters - and _ instead.

To encode bytes into Base64, the input bytes are split into groups of three. Each group of three bytes is then converted into four Base64 characters. The 24 bits of input (three bytes) are instead taken as four groups of 6 bits each, and each of those 6-bit numbers is used to select one of the 64 Base64 characters (recall that \(2^6 = 64\)).

The selection of the Base64 characters is based on the following ordering. Each group of 6 bits is interpreted as an integer and then used as an index into this sequence:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/

As an example, we’ll Base64-encode the ASCII representation of the string

Secr3t.

Character S e c r 3 t

ASCII bits 01010011 01100101 01100011 01110010 00110011 01110100

6-bit groups 010100 110110 010101 100011 011100 100011 001101 110100

Base64 index 20 54 21 35 28 35 13 52

Base64 char. U 2 V j c j N 0

So the result is U2VjcjN0. The decoding process is simply the opposite: for

each Base64 character, find its index in the sequence above and convert that

index into 6 bits. Then reinterpret each group of four 6-bit indexes as three

bytes.

If the input byte sequence’s length is not a multiple of three, the Base64

output is padded with = characters, and for the purposes of determining an

index into the Base64 character sequence, any “missing” bits are taken to be

zero. For example, let’s encode the single byte G. The bits of the ASCII

representation are 01000111. The first six bits are 010001, which is 17 in

decimal: the Base64 character R. To determine the second Base64 character, we

only have two “real” input bits 11, and we take the rest to be zero. So we use

the index 110000, or 48 in decimal: the Base64 character w. Then, since

Base64 always outputs groups of four characters, we add two = characters as

padding. So the final output of encoding G is Rw==.

In Java, you can encode/decode Base64 using the class java.util.Base64. In

Python, there is the base64 module. Linux and macOS have the command-line

utility base64 installed by default. The openssl utility that we’ll look at

later can also encode/decode Base64.

Remember that Base64 is not a file format: it is simply a way of converting between sequences of bytes and sequences of characters1The term “encoding”, in the Base64 context, means converting from bytes to characters. Unfortunately, this is the opposite of how that term is used in the context of character encodings like ASCII and UTF-8: there, “encoding” means converting from characters to bytes. This can be confusing, but as long as you have a clear understanding of the different purposes of character encodings and Base64, you should be able to avoid confusion.. There are file and data formats that use Base64, but it by itself is not a format.

ASN.1#

Now we’ll get into cryptography-specific data formats. The centerpiece of it all is ASN.1 (short for “Abstract Syntax Notation 1”). ASN.1 is a notation for describing a data format; it is not itself a format. Almost all of the cryptographic data you’ll deal with in the real world will be in a format that is defined using ASN.1.

As a simple example, we’ll look at the ASN.1 specification of the data format for an ECDSA signature[ecd02]. Recall that an ECDSA signature consists of two numbers, called \(r\) and \(s\):

Ecdsa-Sig-Value ::= SEQUENCE {

r INTEGER,

s INTEGER }

This means that an ECDSA signature is packaged as a sequence of two variables, which are both integers.

All variables in ASN.1 have a data type. There are several primitive data types,

corresponding to what you see in common programming languages: integers,

booleans, UTF-8 strings, bit strings2Roughly equivalent to byte[] in Java or bytes in Python, but an ASN.1 bit string’s length doesn’t have to be a multiple of 8 bits., timestamps, etc. There are

also two collection types: sequences and sets. In sequences, the order of

the elements matters; in sets, it does not. Sequences and sets can contain

primitive variables (as in the ECDSA example above), or other sequences and

sets.

One often-used primitive type in ASN.1 that has no equivalent in programming is

the object identifier, or OID for short. An OID is a list of numbers that is

generally used to identify a cryptographic algorithm. For example, the ASN.1

object identifier for digital signatures using RSA with SHA-256 is

1.2.840.113549.1.1.11. This will appear, for example, in certificates that are

signed using RSA with SHA-256; this tells the software reading the certificate

which algorithm to use to verify the signature.

Here is one of the messy, annoying parts of this area of cryptography: there is no centralized list of ASN.1 object identifiers. They are spread out across a variety of different standards. Various developers of cryptography software have cobbled together lists of OIDs, with varying degrees of completeness.

Generally, a standard that defines an OID will also specify the ASN.1 structure of the thing the OID applies to. For instance, the above OID for digital signatures using RSA with SHA-256 is defined in a standard[pkc16] that also specifies how to express an actual RSA/SHA-256 signature as an ASN.1 structure.

DER and PEM Encoding#

DER (short for “Distinguished Encoding Rules”) is a method of converting between an ASN.1 structure with values for all the variables, and a sequence of bytes.

There is a huge variety of alternatives to DER, including ones that produce XML instead of raw bytes. However, DER is by far the most commonly used in practice, so we won’t look at all the alternatives.

PEM (short for “Privacy Enhanced Mail”, a weird historical artifact) is simply the Base64 encoding of a sequence of DER bytes, surrounded by an ASCII header and footer that describe what the DER data contains. PEM provides a way for ASN.1 structures to be sent over mediums that can’t handle arbitrary bytes (like email).

It is very important to understand that DER and PEM are not file formats. They are simply ways of turning an ASN.1 structure into a sequence of bytes, and vice versa.

For example, this is a PEM-encoded RSA public key:

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAy3Gj/hHIXzqyauU6TnZA

3WggX7Opf+aD6yjOp7OYjRpdE1kMbpHKf4o6/LGQlz3hhG1QqdO21+9swx5mlh2a

FEbTzRIGA0Dlx4LzjDS+RB1j3KQV6deoRKPMHjAX0o/NV1UyBiNBRZtluHgFgQ1c

U8yvMk2FADLWj4kPC1YxUXc6qMuBRBh0yQ5szKH6xJFXn/mg71MaGnl7b31dhzxi

/nGrg7si1O67h04v35n26srJuT+S4eUAIMWAdCRyjuqH55JxWlNqJ4H+QTS5Md89

d+YWT1F2psUcusIU9Sd9UalIYt2LuOIWUtZp/bWHDU0IXS1RnXkHrk+I1UyWEQtp

vwIDAQAB

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

The first and last lines are the header and footer respectively; the Base64 data

in between is the DER encoding of an RSA public key. Other common header and

footer types you will see are CERTIFICATE, PRIVATE KEY, and

CERTIFICATE REQUEST.

This is the actual ASN.1 structure that is contained within the above PEM data:

SEQUENCE {

SEQUENCE {

OBJECT IDENTIFIER 1.2.840.113549.1.1.1

NULL

}

BIT STRING

SEQUENCE {

INTEGER 2568241417434661966695596864693129854683581277555161622618

3905009822022671305174558677276009809491373047042508123114

1807775395797974833473378716157822484811633648867739125981

3661054010143757453405807222625232935964621682973936871896

6522737707527245472718281207031853120665665845064415891200

7499312027623351534325376711666010553659927999563802129940

8481966659901487472761163978221148630617756220301526979345

0219321573618267111727665154042682721856388921803681160008

6100546780820710375300274326265459971366537137355119916132

7020955068641082538430122402633747933047603908885436402989

1217949404194801532361344485983742399

INTEGER 65537

}

}

At the top level, it contains an ASN.1 sequence of two elements:

The first element is itself a sequence of two variables, specifying the algorithm and parameters that go with the key. The first variable is an object identifier. This OID is defined in the standard PKCS#1, which defines it as

rsaEncryption[pkc16]. That indicates that this is an RSA key, not restricted to use with any particular padding scheme. In this case, the same standard describes what the rest of the ASN.1 structure means; read on for details.The second variable specifies the parameters for the algorithm. Since the OID doesn’t specify any padding scheme, there are no parameters, so this variable is

NULL, a placeholder meaning “nothing here”. If the OID had specified that the key was for PSS signatures, for example, the parameters here would say which mask generation function to use with PSS.The second element of the top-level sequence is a bit string. In general, a bit string is just arbitrary bits. In this case, however, it is actually another DER-encoded ASN.1 structure: a sequence of two integers. The PKCS#1 standard that defines the OID also tells us the meaning of this sequence of two integers: the first one is the modulus of the RSA key (a 2048-bit integer, about 616 decimal digits), and the second is the public exponent (65537).

Certificates#

The ASN.1 structure for certificates is defined in a standard called X.509. Other structures for certificates exist, but X.509 is essentially the only one you will see in the wild.

X.509 is very, very complex, so we’ll only go over the most important aspects of it here. This high complexity has caused real practical problems. It means that any code that parses X.509 data has to be highly complex as well, which makes it more likely to contain bugs that affect security or correctness, and harder to audit for said bugs. As we’ve said before, complexity is the enemy of security.

X.509 defines the following basic fields of a certificate:

Subject. This describes who the certificate belongs to. It may be a person, an organization, or, in the case of TLS, a domain name. The subject has several subparts:

Common name (CN): the name of the person or organization, or the domain name of a website. TLS certificates’ subject common names can include an asterisk; such a certificate is called a wildcard certificate. For example, a certificate with a common name of

*.google.comis valid for any subdomain ofgoogle.com. Common name is the only mandatory field of a certificate’s subject.Organization (O) and organizational unit (OU): if the Common Name is of a person, this identifies the organization and department that the person belongs to. If the Common Name is a domain name, this identifies the organization that owns it.

Country (C): a two-letter code for the country that the subject is located in.

A variety of other fields that specify the location of the subject in more granular detail: state/province, locality, etc.

Subject public key info: the public key in the certificate. This part identifies which algorithm the key is for, and any necessary parameters (e.g. a named curve for an ECDSA key). It also includes the actual key data: exponent and modulus for RSA, named curve and public point for EC keys, etc.

Validity: the time period for which the certificate is valid, in the form of “not valid before” and “not valid after” dates. The latter is also called the expiration date.

Issuer: the entity that signed the certificate. In a self-signed certificate, this will be the same as the subject. The Issuer field has the same subfields as the subject: common name, organization, country, etc.

Serial number: an identifier for the certificate. It has no inherent meaning, and X.509 does not specify how they should be generated. The important thing is that a CA is not supposed to ever issue two certificates with the same serial number.

Version: the version of the X.509 standard that this certificate follows. This is almost always version 3.

Signature algorithm: the algorithm with which the certificate’s signature was produced. This includes not just the signature algorithm and parameters, but also a hash function to be used with it.

Signature: the signature of the certificate, produced by the issuer. The input to the hash function and signing algorithm is all the certificate’s fields except the signature and signature algorithm fields.

X.509 also specifies a huge variety of extensions. These are additional fields of a certificate that can contain all sorts of things. Most of them are too arcane to get into, but here are two important extensions:

Subject alternative names: names other than the Common Name that the subject may be known by. This is most relevant in TLS certificates: these are other domain names that the certificate is valid for. The TLS certificate for

northeastern.edu, for example, hasneu.eduas an alternative name; that domain serves the same certificate asnortheastern.edu.CRL and OCSP endpoints. A CRL endpoint is a URL at which a CRL can be downloaded; if this certificate is ever revoked, its serial number will appear on that CRL. An OCSP endpoint can be queried about the revocation status of this certificate.

Like ASN.1 object identifiers, there is no centralized list of X.509 extensions, and they are spread out across a wide variety of different standards. It is not uncommon for a tool you’re using to view a certificate (including a web browser) to not know what a particular extension in a certificate is.

You may also see a certificate’s fingerprint, especially when viewing TLS certificates in a browser. This is not actually part of the certificate; it is a hash of the whole certificate, signature and all. It can be used to quickly check if two certificates are the same.

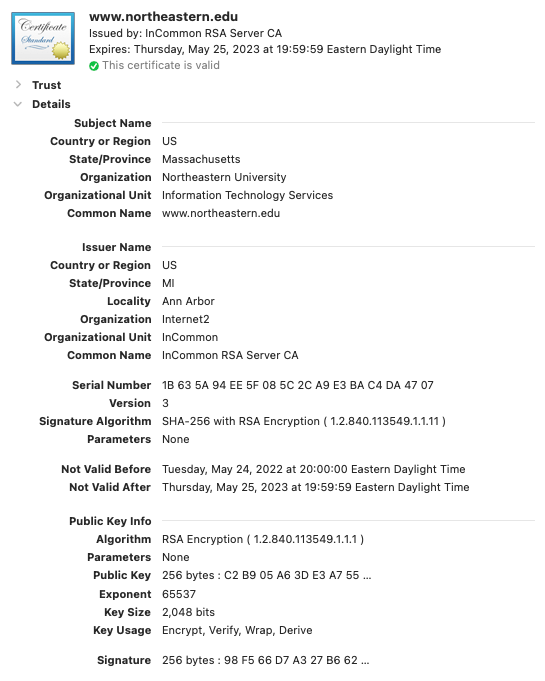

See Fig. 19 for a screenshot of a web browser’s display of the TLS certificate

for www.northeastern.edu.

Fig. 19 The details of the TLS certificate for www.northeastern.edu.#

A long list of extensions is omitted. All of the basic fields are shown; you should be able to explain the significance of all of them except “Key Usage”.

Certificate Signing Requests#

When you want a CA to issue you a certificate, you must send the CA some of the information that you want in the certificate: who the certificate is for, and what the public key is.

A Certificate Signing Request (CSR) is essentially an X.509 certificate without the issuer, serial number, validity period, and signature fields. Those items will be filled in by the CA to produce your certificate.

The overall workflow for certificate issuance is:

Generate a key pair.

Generate a CSR with the appropriate subject data, and the public key from step 1.

Send the CSR to the CA.

Receive a signed certificate in return. Now you can use it with the private key from step 1.

Private Keys#

You will see private keys in one of three formats:

PKCS#8. This is a standard that defines an ASN.1 structure for private keys. Its most notable feature is that it supports encrypting the private key data, using a symmetric cipher and a key derived from a password. Whenever you use an encrypted PKCS#8 private key in software, you’ll need to provide the password to decrypt it. PEM headers/footers for PKCS#8 private keys will say simply

PRIVATE KEY.PKCS#8 is widely supported by software that uses private keys, including web server software (for serving TLS certificates), and Java’s standard library.

OpenSSL format. This format has no formal name, but it is produced by the OpenSSL command-line tool, hence the informal name.

When PEM-encoded, you can distinguish these from PKCS#8 private keys by the header/footer: they will say

RSA PRIVATE KEYorDSA PRIVATE KEYorEC PRIVATE KEYinstead of simplyPRIVATE KEYlike PKCS#8 keys do.OpenSSH. This is specific to the Secure Shell software called OpenSSH. They are always in PEM form, and the header/footer is

OPENSSH PRIVATE KEY. It supports encrypting the key data with a password.

Public Keys#

You’ll mainly see public keys in two formats:

PKCS#1. This is a standard that defines an ASN.1 structure for public keys. It’s used for standalone keys, as well as public keys within X.509 certificates. The PEM header/footer for these is simply

PUBLIC KEY.It’s rare to see public keys by themselves in PKCS#1 format, simply because a bare public key isn’t all that useful; you don’t know who it belongs to. You’ll almost always be dealing with certificates instead.

OpenSSH. Again, this is specific to OpenSSH, the Secure Shell software. It looks very different from the other formats so far, and you never see it in PEM form. A public key is a single line, containing first the name of the algorithm, then the key data in Base64, then the name of the SSH user the key belongs to. For example (some of the key data omitted for space, marked with

[...]):ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIGUI/pq[...]xDsOa4O+RiFCaE user@example.com

PKCS#12, also known as PFX#

PKCS#12 and PFX are essentially interchangeable terms for a specific

file format. You’ll see such files in the wild with the extensions .p12 and

.pfx.

The file format is meant for bundling together multiple ASN.1 structures. It is very, very complex, and files can contain essentially arbitrary combinations of ASN.1 structures. In practice, however, there are only two combinations that you’ll see regularly:

A certificate plus its private key.

A chain of certificates, leading back to a self-signed root.

The contents of PKCS#12 files are encrypted using a key derived from a passphrase. Whenever you use a PKCS#12 file in software, you will need to provide the passphrase.

Most tools that work with PKCS#12 files (including openssl and keytool, both

of which we’ll see later in this chapter) only support a few limited

combinations.

File Extensions#

We’ve covered a lot of data formats, but mostly without mentioning file

extensions. That’s because, unfortunately, the situation is a total mess. With

the exception of .p12 and .pfx for PKCS#12 files, there are no universally

agreed-upon file extensions.

It’s not too uncommon to see files with the extensions .der and .pem. This

is not all that helpful, because it doesn’t tell you what the contents are. A

private key? A certificate? A certificate signing request? A CRL? If the

contents are PEM-encoded, the header and footer will tell you what the contents

are, but if it’s DER-encoded, you’ll have to examine the contents using a software tool like openssl.

Here are a few somewhat often-used extensions for specific types of data. If you

are generating these kinds of files, you should use these extensions for

clarity, not .der or .pem.

Certificates often have the extensions

.ceror.crt.Certificate signing requests usually have the extension

.csr.PKCS#8 private keys sometimes have the extension

.p8, or sometimes.key.OpenSSH public keys always have the extension

.pub.OpenSSH private keys never have an extension.

Software#

OpenSSL#

OpenSSL is an open-source project that consists of two main parts: a software library that does cryptographic operations, and a command-line tool that lets you do those cryptographic operations from the command line.

The OpenSSL library is very widely used; just about any software that uses cryptography but isn’t primarily about cryptography will use OpenSSL. This is generally a good thing — the vast majority of people should not be writing their own implementations of cryptography — but it does mean that bugs in OpenSSL can be tremendously consequential. The infamous Heartbleed bug that caused web servers to leak secret data over the Internet was a bug in OpenSSL[hea].

The OpenSSL command-line tool is usable on all major operating systems. It is installed by default on macOS and most Linux distributions; it should be installable on any Linux distribution through the package manager. This is what you will use to do most real-world cryptographic operations.

Unfortunately, the command-line tool’s interface is pretty bad, by modern standards, and its built-in help is severely lacking. This section will be an overview of how to use it.

Versions#

The messiness begins with the variety of different versions of OpenSSL that are in the wild.

There are two major versions of OpenSSL in widespread use: 1.1.1 and 3.0. They have largely the same features, but all active development is happening on the 3.0 series. The most current version is 3.2, released in late 2023, and it has several modern features that 1.1.1 lacks.

The developers want everyone to be using version 3.0 or newer, but 1.1.1 is still very widespread, because it is shipped by default with the latest versions of macOS and several major Linux distributions.

Complicating the picture further is the existence of OpenSSL forks. A fork of an open-source project is a project that starts life as a copy, but then follows its own separate development path. There are two major forks of OpenSSL, called LibreSSL and BoringSSL. They have slightly different sets of features from OpenSSL itself.

One particular thing to be aware of is that, on macOS, the openssl

command-line tool is actually LibreSSL3You can check by running the command openssl version.. The command-line interface is

largely the same, but the details are different: LibreSSL supports fewer ciphers

and fewer named curves, for example.

The rest of this section will describe the openssl command-line tool, assuming

that it is OpenSSL 1.1.1.

Subcommands#

The tool itself is called openssl. It can do a huge variety of operations. The

operations are organized into subcommands, which you will type on the command

line immediately after openssl, and then follow up with arguments to the

subcommand.

For example, consider this command line:

openssl genrsa -out private-key.pem 4096

These are the parts:

opensslis the tool itself; you run it by putting it as the first thing on the command line.genrsais the subcommand. Its only operation is to generate RSA key pairs.-out private-key.pemspecifies that the generated key should be written to a file namedprivate-key.pemin the current working directory.4096is the length of the key to generate. (To be precise, the length of the modulus in bits.)

The following is a breakdown of some of the most commonly-used subcommands; it is by no means all of them.

Key pair generation subcommands.

genrsagenerates RSA keys.dsaparamgenerates DSA parameter files. A parameter file contains values of \(p\), \(q\), and \(g\), which can be used to generate keys.gendsagenerates DSA keys, using a DSA parameter file4If you thought it’s weird that DSA parameter generation and key generation are done by separate subcommands, but elliptic-curve parameter and key generation are done by the same subcommand, you’d be right. This is just one example of how bad OpenSSL’s command-line interface is..ecparamgenerates elliptic-curve parameter files, and also generates ECDSA keys. A parameter file contains either the name of a named curve, or all the numbers that explicitly describe a curve.genpkeyis a more general subcommand that can generate key pairs for any of the algorithms that OpenSSL supports (including, in newer versions, EdDSA). Unlike the above subcommands, it outputs keys in PKCS#8 format. However, it is harder to use than the above.

Key pair transformation subcommands. These commands can do things like printing keys in human-readable formats, add or remove password protection on private keys, and turn a private key into a public key. They can also convert keys between PEM and DER encoding.

rsaworks on RSA keys.dsaworks on DSA keys.ecworks on ECDSA keys.pkeyis a more general subcommand, which works on key pairs for any of the algorithms that OpenSSL supports. Unlike the three subcommands above, it outputs PKCS#8 private keys.

Certificate subcommands. These can do things like printing certificates in human-readable format, signing and verifying certificates, and converting them between PEM and DER encoding.

x509works on certificates, displaying their contents and signing them.reqgenerates certificate signing requests.verifyverifies the signatures along a chain of certificates.

File format subcommands.

pkcs8works on PKCS#8 data. It can convert non-PKCS#8 private keys into PKCS#8 format, and it can add or remove password protection on PKCS#8 files.pkcs12works on PKCS#12 files, adding or removing things inside them, or extracting parts of them for display.

The

dgstsubcommand implements hash functions. It can also create and verify digital signatures of arbitrary data5If you thought it’s weird that the command-line interface treats digital signatures as an “extra feature” of the hashing subcommand, you’d be right..Utility subcommands. These don’t fit into any particular theme.

asn1parsetakes a DER or PEM input and displays the ASN.1 structure it encodes. This is purely informational; you never need to use this to do a real task.base64does Base64 encoding and decoding. It encodes by default; add the flag-dto decode.encdoes symmetric encryption and decryption. It currently only supports unauthenticated encryption, which, as we’ve seen, is a bad idea.In practice, you’ll never use this — almost all real-life cryptographic work (for people other than cryptography researchers) entails managing asymmetric keys. Symmetric key generation and encryption will happen within some protocol, without a human user needing to do it manually.

Each subcommand has its own set of supported arguments; we won’t go into the details here.

By default, most of the subcommands (other than the key pair generation ones) take input on standard in, and output the same thing on standard out. If you want the subcommand to modify its input somehow, you pass arguments to the command to specify what you want it to do.

An Example#

Let’s say we have an elliptic-curve private key in a file called example.key,

and we want to view its contents in human-readable form. For this, we would use

the ec subcommand. By default, it expects to read a private key in PEM

encoding on standard in, and it outputs the same key in PEM encoding. We need to

modify that flow in three ways:

We want it to read from a file named

example.key, instead of standard in. We do that with the argument-in example.key.We want it to output the key in human-readable form. We do that with the argument

-text.We want it not to output the key in PEM form. We do that with the

-nooutargument.

Here is the contents of the file example.key:

-----BEGIN EC PRIVATE KEY-----

MHQCAQEEIAepeMVGZFCoNtISv5rQY1qjVIE0KlDpWoV1Rd1eDCvPoAcGBSuBBAAK

oUQDQgAE0WX2OubF3MKbQx43NxW3GJ5jB6KycBgh9SzXBrnlqCFCdgTBW73TCoyI

IoSYVUKt1GuFCfQaXfGj1m2yn+M/EA==

-----END EC PRIVATE KEY-----

We run the following command:

openssl ec -in example.key -text -noout

This produces the following output:

Private-Key: (256 bit)

priv:

07:a9:78:c5:46:64:50:a8:36:d2:12:bf:9a:d0:63:

5a:a3:54:81:34:2a:50:e9:5a:85:75:45:dd:5e:0c:

2b:cf

pub:

04:d1:65:f6:3a:e6:c5:dc:c2:9b:43:1e:37:37:15:

b7:18:9e:63:07:a2:b2:70:18:21:f5:2c:d7:06:b9:

e5:a8:21:42:76:04:c1:5b:bd:d3:0a:8c:88:22:84:

98:55:42:ad:d4:6b:85:09:f4:1a:5d:f1:a3:d6:6d:

b2:9f:e3:3f:10

ASN1 OID: secp256k1

This shows the private and public parts of the key, as well as the named curve,

secp256k1, that the key is defined on. (Recall the structure of ECDSA keys: priv is a large number, which gets multiplied by the base point

— part of the definition of the named curve — to produce pub.)

Java KeyStore and keytool#

To load certificates and keys into a Java program (such as a web server or

application server), they will need to be packaged into a file called a Java

KeyStore. The file extension of a KeyStore is .jks. The Java Development Kit

contains a command-line tool called keytool for working with KeyStores.

We won’t go into great detail on how to use keytool here, but only give an

overview of the important points:

Originally, KeyStores were their own proprietary file format, but now they are actually just PKCS#12 files. It’s possible to use OpenSSL to work with them too (using the

pkcs12subcommand), but it’s generally not recommended; if a file is going to be used with Java, you should usekeytoolto work on it. Whether a KeyStore is in the legacy format or PKCS#12 format, the usage ofkeytoolis the same.Like

openssl,keytoolhas subcommands. Unlike OpenSSL, mostkeytoolsubcommands don’t use standard in and standard out, and they don’t expect to work with data in standalone files. Rather, they expect to do operations within KeyStores. For example, when generating a private key, rather than printing it in PEM form on standard out,keytoolwill store it within a KeyStore file that you specify on the command line.Each item in a KeyStore has an alias: a human-friendly name by which you can refer to the item on the command line.

keytoolhas no support for extracting private keys from a KeyStore. If you want to do so, you may be able to useopenssl pkcs12; otherwise, you may need to use a Java program.

PGP and GPG#

PGP (short for Pretty Good Privacy) was the first cryptographic software package that was targeted at everyday computer users. It was released in 1991 by Phil Zimmermann.

We have to talk about PGP because of its historical significance, and because you’ll still see a decent number of people who publish their PGP public keys and put links to them in their email signatures, etc. But this is not a recommendation: the modern consensus among cryptographers is that PGP is bad for various reasons, and it’s time to leave it in the past.

History#

The historical context of PGP is interesting. Recall that in 1991, the Crypto Wars were ongoing; the US government classified implementations of cryptography that used keys longer than 40 bits as “munitions” and restricted their export. PGP included support for longer keys, and copies of it inevitably made their way outside the United States soon after release. This got Phil Zimmermann in trouble with the US government for illegal munitions export. In response, he had the entire source code of PGP published in the form of a physical book, which was sold outside the US. Anyone who was interested could buy the book, then either scan in or type in the source code to get their own copy of PGP. The publication of the book was constitutionally protected free speech in the United States, so Zimmermann was safe from trouble for that.

In 1997, the behavior of the PGP software was described in a standard called OpenPGP[ope07], so that anyone could write software that interoperated with it. The original PGP software went through various owners, and is currently owned by NortonLifeLock (formerly Symantec), a large computer-security company. It is no longer free, and practically nobody uses it.

The spiritual successor of the original PGP is an open-source product called GNU Privacy Guard, or GPG for short. It implements the OpenPGP standard, and thus is compatible with the original PGP. In fact, because the original PGP software has vanished into obscurity, for all practical purposes GPG is considered the reference implementation of OpenPGP. (Yes, this can be confusing.)

From now on, for convenience, we’ll refer to all of this collectively — OpenPGP, and the various implementations of it, including GPG — as simply “PGP”.

Problems#

The problems with PGP are numerous[Pta19].

To establish trust in public keys, PGP used an extremely unwieldy concept called the web of trust. This is a decentralized form of PKI in which users sign each other’s keys to attest that the identity attached to the key is accurate. For example, suppose Alice wants to send a message to Bob, and she has what is supposedly Bob’s public key, but does not trust it. If Alice also trusts Carol’s public key, and sees that Carol has signed Bob’s key, Alice can conclude that Bob’s key is genuine. This is a simple chain of trust, but there could be much longer and more indirect chains too. In effect, every user of PGP functions as a mini-CA.

PGP encourages users to hold “key signing parties”, where they physically meet up to exchange and sign each other’s keys. New users often have trouble finding anyone to sign their keys, which usually leads to people trusting keys even without a chain of trust.

In addition, the web of trust only works if PGP users hold on to the same keys for a long time, which is a whole other problem.

PGP wants its users to have long-lived keys. You’re supposed to generate your PGP key pair once, and keep it forever. People printed their PGP public key fingerprints on their business cards.

One of the most important lessons of the chapter on key management was that long-lived, frequently-used keys are trouble. If your PGP private key gets compromised, there isn’t much you can do about it: there is no reliable revocation mechanism, largely because of how decentralized the web of trust is. PGP’s style of key management is anathema today.

PGP’s cryptography was designed in the 1990s, when the idea of consumer cryptography was very new, and before the cryptography community had learned many of the important lessons that it benefits from today.

Its default symmetric cipher is something called CAST, which you haven’t heard of in this course because it’s not even worth mentioning. It has a 64-bit block size, which, as we saw with DES, is inadequate for modern usage.

Its default asymmetric algorithm is 2048-bit RSA. As we’ve seen in this course, RSA has fallen out of favor, and 2048 bits is the lower limit of acceptable key sizes.

By default, PGP encryption does not have forward secrecy. If an attacker compromises your private key, they will be able to read everything that was sent to you under that private key.

By default, PGP does not do authenticated encryption. That concept was developed long after PGP, but it is now considered essential, even mandatory in any context other than full disk encryption.

If PGP could have evolved past these insecure choices, maybe it could have been salvageable, but instead…

PGP insists on backwards compatibility, which makes it hard or impossible to drop the insecure behaviors and algorithms of old versions and move on to better alternatives.

PGP’s user interface has always been difficult to use, somewhat notoriously so[WT99]. This is a consequence of PGP’s complexity, which in turn stems from the inherent complexity of the web-of-trust model, and the insistence on backwards compatibility.

As we’ve seen, complexity is the enemy of security. The more choices a user needs to make, the more chances they have to make the wrong choice. PGP required users to understand a huge mess of concepts, and make a lot of choices, to use it at all. PGP delegated key management to end users, which is now known to be flatly wrong. (If you use something modern like Signal, you never have to think about cryptographic keys even once.)

PGP Email#

The most common context where you might see PGP used (or supposed to be used) is email. People post a PGP public key so you can use it to send that person encrypted email. But here’s the thing: don’t use PGP for email.

In fact, don’t encrypt email at all. If you wouldn’t put something into an email unencrypted, don’t put it in an email at all.

Email is based on a set of protocols which are all unencrypted by default. Email applications are built on that assumption. Encryption has been bolted onto the system well after the fact, and this is a recipe for failure. All that it takes to ruin everything is for one participant in the thread to reply to the thread without encryption, quoting the entire contents of the thread to that point. Even PGP encryption within email has had notable vulnerabilities because of implementation details[P+].

For a communication channel to be secure, it must be designed for security from the ground up. Adding security after the fact will never suffice.

Key Takeaways#

Base64 is a way of converting a stream of arbitrary bytes into characters that are not likely to be mangled in mediums like email.

ASN.1 is a notation for describing a data format. It is used to define a wide range of cryptography-specific data formats.

DER is a way of converting an ASN.1 structure, with values filled in, into a sequence of bytes.

PEM is simply a sequence of DER bytes, Base64-encoded, and surrounded with an ASCII header and footer that identifies what the contents are (a certificate, a public key, a private key, etc.).

X.509 is an ASN.1 format for certificates. An X.509 certificate can contain a huge amount of information, but the most important parts are the subject (who owns the certificate), the public key, the validity period, the issuer (who signed the certificate), and the signature.

A certificate signing request is just the subject and public key parts of a certificate. It is what you send to a CA to get a certificate issued.

Private keys are usually in an ASN.1 format called PKCS#8. It supports password protection (using a symmetric encryption key derived from the password).

PKCS#12, also known as PFX, is a file format for bundling several items together. It is most commonly used to store a certificate together with its private key, or a chain of certificates.

Java KeyStore is a file format for loading certificates and keys into Java programs. It is actually just PKCS#12 under the hood. You work on KeyStores using the

keytoolcommand-line program that is included in the Java Development Kit.OpenSSL is an open-source project. It contains the command-line tool

openssl, which is used to do most real-life certificate and key management tasks.Don’t use PGP or GPG.

Don’t encrypt email. If something is too sensitive to be sent in an unencrypted email, it shouldn’t be in an email at all.