Block Ciphers#

In the previous chapter, we saw an example of a stream cipher, one of two common types of symmetric-key cipher. The other kind is a block cipher. Block ciphers transform a fixed-size group of plaintext bits into ciphertext bits, and vice versa. The most common block size for modern block ciphers is 128 bits.

To encrypt data that is larger than a block, you must use a block cipher mode of operation, which is the topic of the next chapter. To encrypt data that is smaller than a block, you must apply padding, which we’ll cover in this chapter.

There are an enormous number of published block ciphers, and they use a wide variety of different structures and techniques. We will only look at one in detail here: the one that is by far the most commonly used in the real world.

AES: Advanced Encryption Standard#

AES is the only block cipher that new applications should use. It was standardized in 2001 by NIST[aes01a].

AES operates on blocks of 128 bits, and supports key sizes of 128, 192, or 256 bits. (These variants are sometimes referred to as AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256.) Like ChaCha20, and practically all block ciphers, AES has a round-based structure. AES’s number of rounds depends on the key size: 10 rounds for a 128-bit key, 12 rounds for a 192-bit key, and 14 rounds for a 256-bit key. Each round consists of four simple, distinct operations, which we’ll see below.

You don’t need to know all the details of how AES works to use it, and the aim is not to show you how to implement it. I simply think it’s revealing and interesting to see what the world’s most widely-used encryption algorithm actually does, on a bits-and-bytes level, to encrypt data, so that it’s easy to get the data back with the key, and nearly impossible without it.

AES encryption works as follows. Before encrypting any data, the key is expanded into several subkeys, which are each 128 bits (the same size as the block). The number of subkeys is equal to the number of rounds plus one. The process of expanding the key into subkeys is called the key schedule, which we’ll look at later.

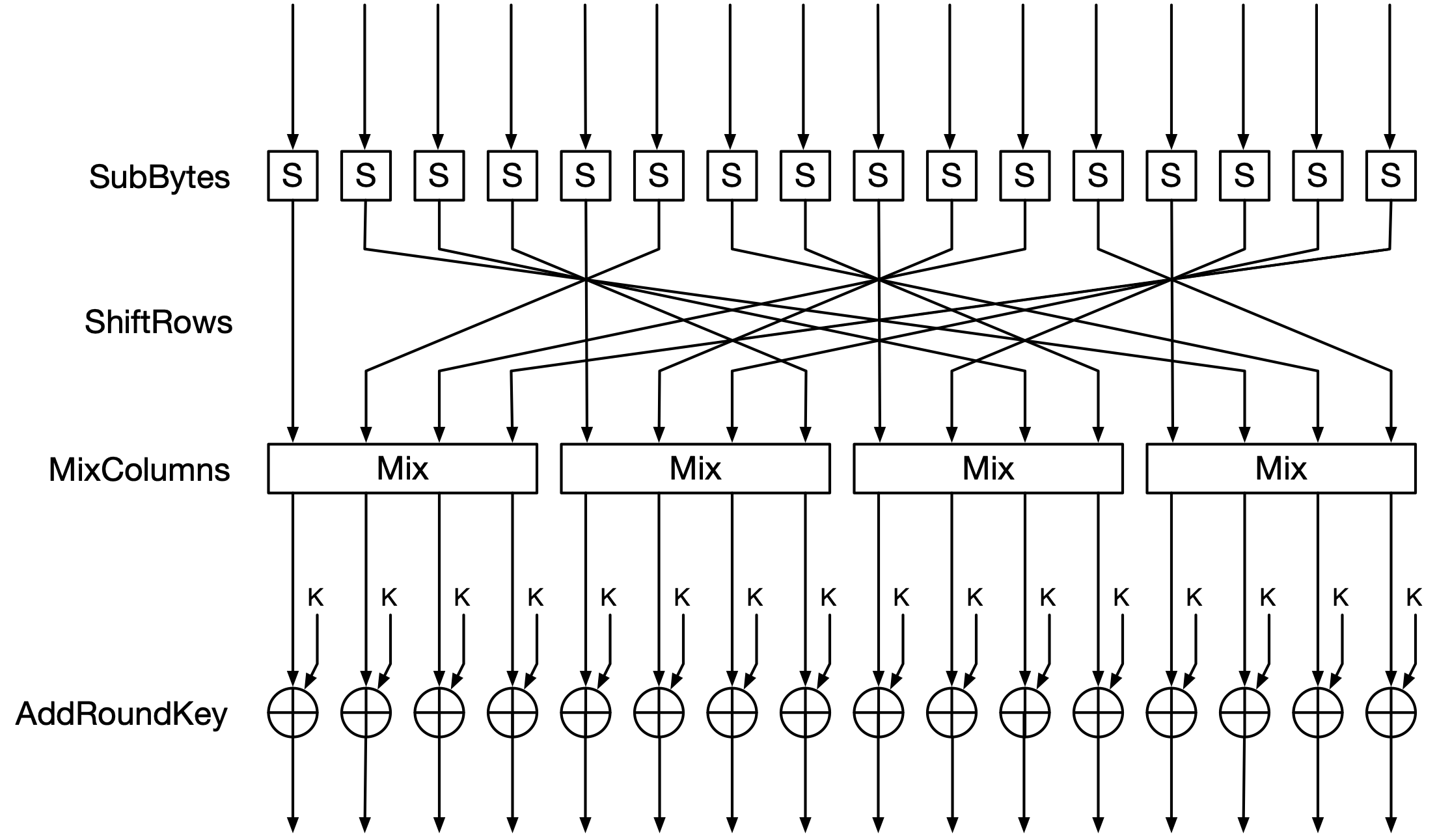

After completing the key schedule, the first subkey is XORed with the block, byte-by-byte. Then all but one of the requisite number of rounds is performed, each of which consists of these four operations:

SubBytes: each byte of the block is replaced with a different one according to a fixed lookup table. This kind of lookup table is common to many block ciphers, and is called an S-box (short for “substitution”).For example, the byte

0x00is replaced with0x63.0x01is replaced with0x7C, and0x02with0x77. There is no discernible pattern to the outputs.Importantly, this substitution is reversible, because every input byte maps to a unique output byte. Therefore, during decryption, reversing this operation means replacing the byte

0x63with0x00and so on.ShiftRows: the bytes of the block are reordered. If the bytes of the input toShiftRowsare \(b_0, b_1, ..., b_{15}\), then the output ofShiftRowsis:\[b_0, b_5, b_{10}, b_{15}, b_4, b_9, b_{14}, b_3, b_8, b_{13}, b_2, b_7, b_{12}, b_1, b_6, b_{11}\]This is derived from treating the block as a \(4 \times 4\) matrix of bytes, with sequential bytes going down the columns, then rotating the last three rows of the matrix to the left by 1, 2, and 3 bytes respectively. So:

\[\begin{split} \begin{bmatrix} b_0 & b_4 & b_8 & b_{12} \\ b_1 & b_5 & b_9 & b_{13} \\ b_2 & b_6 & b_{10} & b_{14} \\ b_3 & b_7 & b_{11} & b_{15} \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} b_0 & b_4 & b_8 & b_{12} \\ b_5 & b_9 & b_{13} & b_1 \\ b_{10} & b_{14} & b_2 & b_6 \\ b_{15} & b_3 & b_7 & b_{11} \end{bmatrix} \end{split}\]Reading down the columns from left to right gives the new order of the block bytes.

MixColumns: this is the trickiest step to understand. The block is again viewed as a \(4 \times 4\) matrix, and it is multiplied by a matrix of constants:\[\begin{split} \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 & 3 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\ 3 & 1 & 1 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} b_0 & b_4 & b_8 & b_{12} \\ b_1 & b_5 & b_9 & b_{13} \\ b_2 & b_6 & b_{10} & b_{14} \\ b_3 & b_7 & b_{11} & b_{15} \end{bmatrix} \end{split}\]However, this is not a standard matrix multiplication. Its structure is the same, but the multiplications and additions of matrix elements are nonstandard. They are done using Galois-field arithmetic, which is beyond our scope here, but is summarized in the appendix.

Note that, because of the way matrix multiplication works, each column of the resulting matrix depends only on the corresponding column of the block. For example, the leftmost column of the result depends only on \(b_0\) through \(b_3\). This is why the step is called

MixColumns; it is essentially four independent operations, one on each column.AddRoundKey: XOR the next subkey with the block, byte-by-byte.

After doing all but one of the requisite number of rounds, a final round is performed; the final round is different in that is skips the MixColumns step.

AES decryption is similar. The key schedule is the same as for encryption, but the subkeys will be used in the opposite order. After completing the key schedule, the block is XORed with the first subkey (i.e. the last subkey that was used during encryption).

Then, all but one of the requisite number of rounds is performed, consisting of the following steps. Note how the order of the steps

differs from their order during encryption. Think about stepping backwards

through the encryption process, and take some time to convince yourself that

this is correct, keeping in mind that the last encryption round skips the

MixColumns step.

InvShiftRows: likeShiftRows, but simply rotate the rows to the right instead of the left.InvSubBytes: likeSubBytes, but using a different S-box that undoes the substitutions performed by the S-box for encryption.AddRoundKey: exactly the same in decryption as it is in encryption, thanks to the self-inverting nature of bitwise XOR.InvMixColumns: likeMixColumnsbut multiplying the block by a different constant matrix:\[\begin{split} \begin{bmatrix} 14 & 11 & 13 & 9 \\ 9 & 14 & 11 & 13 \\ 13 & 9 & 14 & 11 \\ 11 & 13 & 9 & 14 \end{bmatrix} \end{split}\]Because of how AES’s Galois-field arithmetic works, this inverts the multiplication of

MixColumns.

Afterwards, perform a final round like the above, but without the InvMixColumns step.

Note that each of a round’s operations serves a specific purpose:

SubBytesprovides non-linearity. Without this step, it would be possible to express each bit of the ciphertext as a simple function of plaintext and subkey bits, involving only XOR and finite field multiplication. This would be solvable algebraically, making the cipher trivially weak.It also provides confusion, by entirely replacing bytes after XORing in the subkey.

ShiftRowsandMixColumnstogether provide diffusion, making it so that block bits depend on other block bits.MixColumnsmakes groups of four adjacent bytes depend on each other, andShiftRowsmoves bytes around between those four-byte groups. After all the rounds are complete, every bit of the ciphertext depends on every bit of the plaintext.AddRoundKeyensures that every bit of the ciphertext depends on the key.

This general structure is common to many block ciphers, and is called a substitution-permutation network, or SPN. The substitution part provides non-linearity and confusion, and the permutation part provides diffusion.

See Fig. 7 for a diagram of a single non-final encryption round.

Fig. 7 One round of AES encryption. Each arrow represents one byte.#

Key Schedule#

Virtually all block ciphers have a key schedule, which transforms the key into the shape required by the cipher’s encryption and decryption procedures.

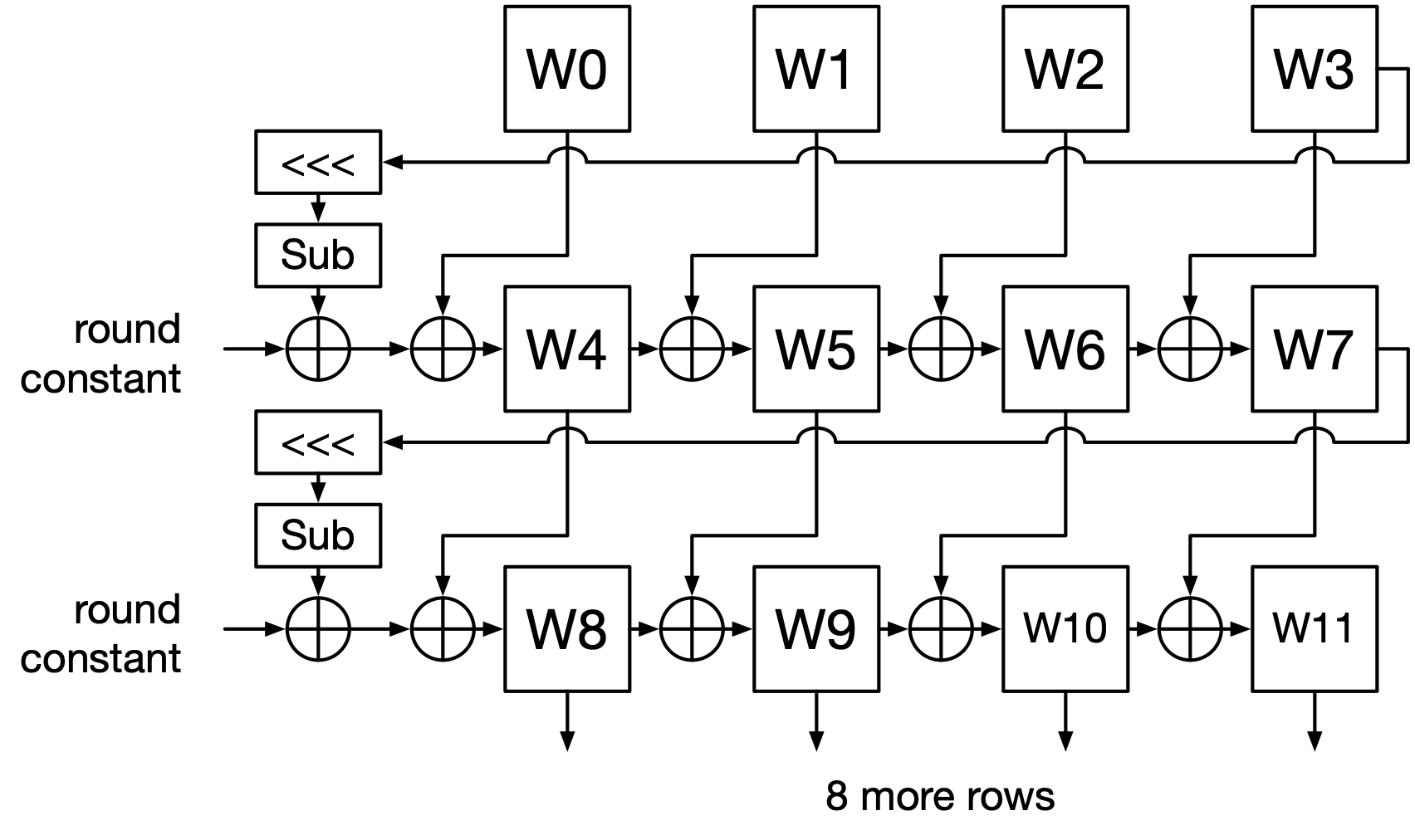

AES’s key schedule is relatively simple. It operates on 32-bit (4-byte) integers, which are called words. We can visualize it as filling in a table, where each row contains as many words as there are in the main key. We will fill in the table from top to bottom. See Fig. 8.

The first row of the table is populated with the key itself, converted from 16 bytes to four 4-byte words using the big-endian convention.

To fill in subsequent rows:

The first word in the row is the XOR of the word above it with a transformed version of the last word in the row above. The transformation is to rotate that word one byte to the left, then apply the S-box from the encryption process to each byte, and then XOR in a round constant. There are ten fixed round constants.

The rest of the words are populated by XORing the word to the left with the word above. There is one exception: for 256-bit keys, to populate the fourth word in the row, the encryption S-box is applied to the word to the left (the third word in the row) before XORing it with the word above.

This is repeated until there are enough total words in the table to form the right number of subkeys (i.e. the number of rounds plus one). Recall that each subkey consists of 128 bits, or four words.

In this key schedule, you can see similar techniques to the encryption process, resulting in non-linearity (from the S-box applications) and diffusion (from the rotations, and subkeys’ dependence on other subkeys).

Fig. 8 AES key schedule for a 128-bit key.#

\(W_0\), \(W_1\), etc. are each 32 bits, and each row is the subkey for one round of encryption/decryption. \(W_0\) through \(W_3\) are the original key.

Why Have a Key Schedule?

You may wonder: why bother with a whole separate procedure to expand the key? Why not simply require a bigger key, with enough bits to provide all the necessary subkeys? There are two main reasons.

First, the aim of any cipher is to achieve the requisite security level with as small of a key as possible. Smaller keys are simply more practical to create, store, and otherwise manage. AES requires at least 1,408 bits’ worth of subkey; it would be much less practical to use if it needed 1,408-bit keys instead of 128-bit keys.

Second, simply having a long key and using it directly as subkeys could — depending on the cipher’s structure — result in some keys being more secure than others; for example, if the long key consisted of the same 128-bit sequence repeated many times. A good key schedule serves to diffuse each key bit across many subkey bits, preventing such regular structure from appearing in the subkeys. The most widely-used cipher before AES has a key schedule, but it is simple enough to be a weakness in this exact way.

Cryptanalysis#

AES has a design that was unusual for the time when it was created. It has a relatively simple mathematical structure, and ciphers in that shape had not been widely cryptanalyzed. Early in the cipher’s life, there was some concern that there would be some novel algebraic approach to breaking AES. So far, though, nothing like that has emerged.

The best attack against AES is a chosen-plaintext attack that can recover a 128-bit key with \(2^{126}\) steps[TW15], which is a factor of four less than a brute-force attack would take. Although this means that AES is not as secure “as advertised”, such an attack is still nowhere near feasible.

There are better attacks that require certain conditions. They are of a class called related-key attacks, in which the attacker can see plaintext/ciphertext pairs that were encrypted under keys that are unknown, but mathematically related in some way. Some of these attacks can recover a key with about \(2^{96}\) steps[BKN09]. In practical usage, related keys should not be a concern — keys should be chosen randomly — but these attacks are still important results.

There are related-key attacks with much better results against a lower number of rounds of AES. (This is common in block cipher cryptanalysis: attacks that initially target reduced-round variants of a cipher, which can perhaps later be improved to work on more rounds.) The best related-key attack works against 9 rounds of AES-256, and can recover the key in \(2^{39}\) steps, which is well within the realm of feasibility[BDK+09]. However, it does not work against all 14 rounds of AES-256.

To some cryptographers, this is too close for comfort: a feasible attack against 9 out of 14 rounds. This problem could easily have been mitigated by increasing the number of rounds, but that would come at the cost of performance. The AES designers made the decision that the numbers of rounds they specified were sufficient for security. And remember: this is a related-key attack, which should be impossible in real-world usage.

The bottom line is that there is no cryptanalytic attack that comes anywhere close to breaking AES for practical purposes. An attack that takes \(2^{126}\) steps is still completely infeasible, even if it counts as an academic break of the cipher.

Padding#

If you have less data to encrypt than one whole block, you add padding to the data so it fills an entire block. (It may not seem common to want to encrypt less than a block of data, but every block cipher mode involves chopping up the plaintext into block-sized pieces, and after doing so, there is often a less-than-block-sized piece left over, which must be padded.)

The important requirements for a padding scheme are that it fill the required space, and that it be possible to unambiguously identify the padding bytes so they can be removed.

Some block cipher modes, which we’ll see in the next chapter, do not require padding, but at least one commonly-used mode does.

There are several different padding schemes, and we’ll only look at the two most common ones here. The choice of padding scheme is not critical. The first one, PKCS#7, is generally the most commonly used.

PKCS#7#

PKCS#7 is a standard published by RSA Security. It specifies1You will also see this padding scheme referred to as PKCS#5 (including by Java’s cryptography library). The distinction is pedantic, and the padding logic itself is identical. many things, one of which is a padding scheme for block ciphers. It is simply to determine how many bytes of padding are required to make the plaintext length a multiple of the block size — call that number \(k\) — and then append \(k\) bytes of value \(k\). Here is an example of padding a plaintext that requires 5 bytes of padding to fill a 16-byte (128-bit) block:

byte position 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

unpadded block 7b e9 92 de ad cf c3 68 2b 54 d3

padded block 7b e9 92 de ad cf c3 68 2b 54 d3 05 05 05 05 05

To unpad the plaintext, look at the last byte of the last block, and remove that many bytes from the end of the plaintext, verifying that each one has the expected value.

You may have spotted a problem with this: what if the plaintext length is already a multiple of the block size, so no padding is required? How can the unpadding logic tell that this is the case, especially if the final byte of such a plaintext is a plausible number of padding bytes?

The answer is that all plaintexts get padded, even if their length is already

a multiple of the block size. In that case, the padding would consist of sixteen

0x10 bytes.

ANSI X9.23#

The required number of padding bytes \(k\) is determined, then \(k-1\) random bytes are added. (Some implementations just add all zero bytes for simplicity; that complies with the standard.) Then a final byte of value \(k\) is added. Unpadding is similar as in PKCS#7: look at the value of the last byte, and remove that many bytes from the end; the difference from PKCS#7 is that the values of all but the last padding byte are ignored.

byte position 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

unpadded block 7b e9 92 de ad cf c3 68 2b 54 d3

padded block 7b e9 92 de ad cf c3 68 2b 54 d3 88 2a 7c 18 05

Similarly to PKCS#7 padding, at least one padding byte must be added, regardless of the original length of the plaintext, or else the padding can’t be unambiguously identified.

History#

It’s worth taking a quick tour of the history of block cipher development, because it demonstrates the broad strokes of the evolution of computerized cryptography as a whole.

Data Encryption Standard#

The first published cipher designed for electronic devices was called the Data Encryption Standard, or DES for short[fip]. It was developed in the late 1970s. It has a key size of 56 bits, and a block size of 64 bits. There are more details about the internals of DES in the appendix.

Unlike AES, DES’ original purpose was not to serve as a cipher for everyone. Rather, it was meant primarily for the US government to use for sensitive information.

The process by which DES was designed is a good illustration of the state of cipher research in that time. There was virtually no academic research on ciphers; it was the purview of governments and large corporations. DES was designed by a team at IBM, in response to a public appeal for a new algorithm design by the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), the predecessor to the modern NIST. (This was actually NBS’s second call for designs — their first one resulted in no acceptable designs, which reinforces the earlier point about the state of public cipher research.)

NBS requested the assistance of the US National Security Agency (NSA) in evaluating submitted cipher designs. The NSA pushed for changes to the DES proposal that immediately aroused suspicion among outsiders. IBM wanted a key length of at least 64 bits, but the NSA wanted 48 bits; the end result of 56 bits was a compromise. The obvious explanation was that the NSA wanted to be able to break the cipher by brute force; being the NSA, they had easy access to the kind of funding and computing power that would require. Even in the late 1970s, when computing power was a fraction of what it is today, there was concern that a 56-bit key was short enough to be brute-forced.

The NSA also made publicly-unexplained changes to DES’s S-boxes (which serve a similar purposes to AES’s). This looked to outsiders like a way of introducing a backdoor: a statistical weakness in the algorithm that only the NSA knew how to exploit2An example of the problem that nothing-up-my-sleeve numbers are meant to counteract..

Decades later, in 1993, the academic researchers Eli Biham and Adi Shamir developed a cryptanalytic technique they called differential cryptanalysis[BS93]. They discovered that DES was resistant to the technique, and furthermore, that small changes to the S-boxes significantly weakened that resistance. It turned out that theirs was at least the third independent discovery of differential cryptanalysis. The IBM team had discovered it themselves in analyzing their creation, and they had in turn found out that the NSA already knew about it. The NSA’s modifications to the S-boxes had not introduced a backdoor into DES; on the contrary, they had made DES stronger. The NSA asked IBM to keep the technique secret, as they didn’t want rival powers to learn about it. It was only after Biham and Shamir’s rediscovery that Don Coppersmith, one of the DES designers at IBM, publicly acknowledged that IBM knew about it.

The standardization of DES marked the start of the era of open academic study of cryptography. Two important modern cryptanalysis techniques — linear cryptanalysis, and the aforementioned differential cryptanalysis — were first developed as attempts to break DES, and subsequent cipher designs had to be resistant to them as a matter of course. DES’s design inspired the creation and analysis of similar ciphers. Though it was a flawed algorithm from the start, and its development process did little to inspire trust, it pushed the field of cryptography forward significantly.

Interregnum#

Because of DES’s small key size, and the ever-increasing amounts of processing

power at our disposal (and the ever-decreasing cost of same), brute-force

attacks against 56-bit single DES are within the means of individuals. A

single Nvidia graphics card can recover a 56-bit DES key by brute force in less

than a month. About $100,000 worth of purpose-built hardware can brute-force a

key in just over a day — an insignificant amount of money for a government

agency. In addition, there are now precomputed ciphertexts for the plaintext

1122334455667788 encrypted with most keys, which allow key recovery in under

30 seconds in most cases.

DES’s small block size is an issue because it puts a rather low limit on the total number of possible blocks: \(2^{64}\), to be exact. If we have \(\sqrt{2^{64}} = 2^{32}\) ciphertext blocks, the probability that two of them will be the same is around 50%. (We will justify this mathematically in a later chapter.) \(2^{32}\) blocks is 32GiB of data, which by modern standards is a very manageable amount — you can buy a USB stick of that capacity for about $10. If you have two identical ciphertext blocks, you know that the corresponding plaintext blocks are identical, which leaks information about the plaintext. Therefore, it’s not secure to use DES to encrypt that much data under a single key. When DES was designed, 32GiB seemed like an enormous amount of data, but modern computing power has caught up to it.

As a solution to the problem of DES’s small key size, a variant called Triple DES was published in the early 1980s. Sometimes shortened to 3DES, Triple DES consists of applying DES three times, with three different keys, effectively making it a 168-bit key.

By the late 1990s, it was clear that DES was reaching the end of its useful life, mostly due to its small key size, but also to its small block size and its poor performance in software. Triple DES mitigated the key size problem, but had the same block size problem, and made performance even worse.

It was equally clear, however, that there was no obvious successor. Academic and corporate cryptographers, who saw the need for a successor, had churned out a huge variety of new block ciphers. Some were primarily research projects, but some were legitimately aimed at replacing DES as the cipher for general use. Because there were so many ciphers to analyze, researchers’ attention was divided, and few ciphers got enough analysis to establish widespread confidence in their security. Many also turned out to be insecure, and some were covered by patents, which limited their adoption. In at least one case, the open cryptographic community did not trust the motives of the organization that designed the algorithm: the NSA.

AES Competition#

Recognizing the problems with this situation, in 1997, NIST put out a call for new block cipher designs. They were to be designed and evaluated in the open — that is, not in secret — and NIST would choose one to standardize after a rigorous competition[aes01b]. This was crucial in creating public trust in the outcome.

Over the next year, academic cryptographers created and submitted designs; in total there were fifteen submitted. In 1998 and 1999, NIST held two conferences to discuss the candidate algorithms, and in August of 1999 they announced that the field would be narrowed from fifteen candidates to five: MARS, RC6, Rijndael, Serpent, and Twofish. These five algorithms came to be called the AES “finalists”. All the finalists are well-regarded, and it’s likely that any of them could have served well as AES.

NIST, and the cryptographers participating in analysis, evaluated the algorithms based on many factors, of which security was just one. Since the algorithm eventually selected as AES would become very widely used, NIST wanted one that would run efficiently in a wide variety of computing environments: hardware implementations, software implementations, embedded devices like smart cards, environments with very limited memory, and so on.

In October 2000, NIST announced that it had chosen a winner: Rijndael3Pronounced, roughly, “rhine-doll”, Rijndael is named after its two designers, Vincent Rijmen and Joan Daemen., which we now know as AES. It’s notable that Rijndael was chosen in spite of broad agreement that it was not the most secure of the finalists. What gave it the advantage was its balance of security and speed.

The introduction of a standardized cipher, thoroughly analyzed by the academic community, highly performant, blessed by the United States government (including the NSA), unpatented, and fully public, brought a measure of certainty to practical cryptography. With AES, no one really had to think about the choice of a symmetric cipher anymore: AES was the default answer, and there was no good reason to choose a different one. It remains the default answer to this day, and for the foreseeable future.

Settling on a single cipher also allowed CPU manufacturers to build hardware AES implementations into their designs, which allows for performance greatly increased over software implementations, and makes side channel attacks much more difficult. If your computer contains an Intel CPU made in the last 12 years, or an Apple Silicon CPU, it has hardware AES support in it[int]; so do newer iPhones. This further entrenches the choice of AES as the default symmetric cipher: the wide availability of hardware AES implementations gives it a huge performance advantage over other ciphers, which largely must settle for software implementations.

NIST’s AES competition was considered a great success, and it has inspired similar competitions to standardize other cryptographic building blocks. NIST itself ran a competition from 2007 to 2012 to choose a new hash function, which ended up being standardized as SHA-3. We will look at hash functions in detail in a later chapter.

One interesting side effect of the standardization of AES is that new research in block ciphers has somewhat dried up. There’s no real need for a new block cipher, so cryptography researchers have mostly turned to other topics. This could become a problem if the time ever comes to replace AES.

Key Takeaways#

AES is a block cipher, the only one that new applications should use, and pretty much the default choice of symmetric cipher for any application. It has a 128-bit block size, and can use keys of 128, 192, or 256 bits.

AES is structured in a way that was somewhat novel at the time it was designed, which made some researchers nervous about it, but in the 21 years since its standardization, no practical attacks against it have been found.

AES was the result of an open, public competition among algorithm designers: the first of its kind. It was considered a huge success.

Padding is a reversible way of adjusting the length of data to match the block size of a block cipher. Padding validation is a very common vector for side channel attacks.

PKCS#7 padding is the most common padding scheme in practice. However, block cipher modes that don’t require padding are becoming more widely used.

DES was the standard symmetric cipher before AES. It has a 64-bit block size and 56-bit key size. The key size in particular makes it extremely insecure, and it should be replaced if at all possible.

See Also#

A gentle tutorial on linear and differential cryptanalysis.

An online service to brute-force DES. If your plaintext is

1122334455667788, you can use it for free!