Authenticated Encryption#

In this chapter, we’ll introduce real-world algorithms for the first time. This will show how to do authenticated encryption; that is, how to combine a symmetric cipher and a message authentication code to create confidentiality, integrity, and authentication.

In practical usage, all encryption should be authenticated encryption. Confidentiality alone, without integrity and authentication, is not secure. In this chapter, we’ll see one easy way to exploit unauthenticated encryption.

The purpose of this chapter to demonstrate several concepts that are broadly applicable in cryptography, using two particularly simple real-world algorithms as examples.

ChaCha20, a Stream Cipher#

In the last chapter, we saw the repeating-key XOR cipher and the one-time pad. Both of those ciphers performed encryption by XORing a sequence of key bytes with plaintext, byte-by-byte. This is a convenient mechanism to build a cipher around, because it means that encryption and decryption work exactly the same way.

We saw that the repeating-key XOR cipher is grossly insecure, and the one-time pad is perfectly secure but highly impractical. However, we can adapt those ideas to build a practical, secure cipher. The idea is to use a fixed-length key to generate an arbitrarily-long, non-repeating sequence of bytes. Any cipher that does this is called a stream cipher, and the sequence it generates is called the keystream.

The keystream must look like it was randomly generated, but it must not be truly random. In a later chapter, we’ll take a closer look at what exactly that means. For now, there are two important things about the keystream:

The keystream is reproducible, meaning that anyone who has the original key can reconstruct the keystream with complete accuracy.

Even if an attacker knows all of the keystream up to a certain point, they cannot predict the keystream that comes after that point, without having the original key.

The alternative to stream ciphers as a category is block ciphers. We will cover those in great detail in a later chapter.

We’ll look at a popular stream cipher called ChaCha20, which was first published in 2008 by Daniel Bernstein[NL18]. It is a very simple cipher — simple enough to memorize — and we’ll look at it in detail.

Setup#

ChaCha20 takes a 256-bit key. Its basic structure is to create an array of 512 bits, containing the key and a few other values, then run a scrambling function on the array twenty times (hence the “20” in the name), and use the resulting array as 512 bits of keystream. Repeat that process as many times as necessary to generate the required amount of keystream.

To start, the 512-bit array is treated as a \(4 \times 4\) matrix of 32-bit words, and initialized as follows; each box represents one 32-bit word.

+---------+---------+---------+---------+

| "expa" | "nd 3" | "2-by" | "te k" |

+---------+---------+---------+---------+

| . . . |

+ . . . . . . . . Key . . . . . . . . +

| . . . |

+---------+---------+---------+---------+

| Counter | Nonce |

+---------+---------+---------+---------+

The simplest parts of this are the two middle rows, which are initialized with the cipher’s 256-bit key1All conversions between bytes and words in ChaCha20 use the little-endian convention.; and the counter, which is a 32-bit integer. When generating the first 512 bits of keystream, the counter is initialized to zero. When generating the next 512 bits, the counter is initialized to one, and so on.

The other two parts are examples of two important concepts in cryptography: nothing-up-my-sleeve numbers, and nonces.

Nothing-Up-My-Sleeve Numbers#

The top row, the first four 32-bit words, contain the phrase expand 32-byte k, encoded as ASCII.

Most algorithms have variables that need initial values, and algorithms are often more effective if those values have no discernible pattern. However, initializing with inexplicable patternless values can be a cause for suspicion: in some cases, algorithms’ security can be weakened by using carefully chosen initial values. (We’ll see examples of such suspicion in later chapters on block ciphers, random number generation, and elliptic curves.)

Therefore, algorithm designers often derive their initial values from some well-known source, unrelated to cryptography, to demonstrate that they have “nothing up their sleeve”. One formerly popular cipher used digits of \(\pi\) as nothing-up-my-sleeve numbers; a currently-popular hash function uses square roots of prime numbers. ChaCha20 just uses an English phrase.

Nonces#

The last 96 bits of the block are a nonce. The word is a shortening of number used once.

Nonces are our first encounter with a common thing in cryptography: a piece of data that is neither plaintext, nor ciphertext, nor key; and that must have certain specific properties in order for the algorithm to be secure. Properly creating and securing such pieces of data is a significant part of the difficulty of implementing cryptography correctly in practice.

Nonces, as the name’s origin suggests, must be unique. In stream ciphers in particular, a nonce must never be used to encrypt two plaintexts with the same key (with the counter starting from zero for each plaintext). If you do that, you’ll be XORing both plaintexts with the same keystream, and that means the ciphertext-only attack on the repeating-key XOR cipher applies. Remember how fast and easy that attack was? In this context, it’s a little harder, but it’s barely an inconvenience to a skilled attacker. Reusing a nonce is a catastrophic failure of security.

It’s worth repeating: the nonce of a stream cipher is the only thing that stops the stream cipher from turning into the repeating-key XOR cipher.

In stream ciphers, nonces do not have to be kept secret, and it’s OK if they’re predictable. In some other algorithms, however, they must be kept secret. We’ll call this out specifically when we see those cases.

In practical usage, nonces for stream ciphers are often an incrementing counter, which counts how many plaintexts have been encrypted with a particular key. That guarantees uniqueness until it reaches \(2^{96}\) (which, as you may recall, is an enormous number, which would never be reached in practice). This is not to be confused with the counter in the ChaCha20 matrix, which counts 512-bit blocks of a single plaintext.

Caution

Nonce reuse is our first example of how an elementary, minor-seeming mistake can completely vaporize the security of a cryptographic algorithm. We’ll see this kind of thing a lot. Cryptography is hard, and this is one reason why!

This is why, although you will almost certainly never write an implementation of ChaCha20, it’s good to understand how it works, so that “don’t reuse a nonce” isn’t just a little piece of advice that’s easy to forget. This is also why we went through the process of breaking the XOR cipher in such detail!

Round Function#

As we saw, ChaCha20 works by initializing the \(4 \times 4\) matrix of words as shown above, then running a scrambling function on that matrix twenty times. The scrambling function is more properly called a round function, and each repetition of it is called a round.

Essentially all symmetric ciphers have a round-based structure: they define some core transformation, and repeat it some number of times. This structure is useful for several reasons. A non-round-based cipher with an equivalent security level to a round-based cipher would have to be far more complex, which would make both implementation and cryptanalysis harder. In a round-based cipher, you only need to implement or analyze the core transformation. The round-based structure also gives the cipher’s designers an easy way to tune the cipher for performance or security: more rounds are slower but more secure; fewer rounds are faster but less secure.

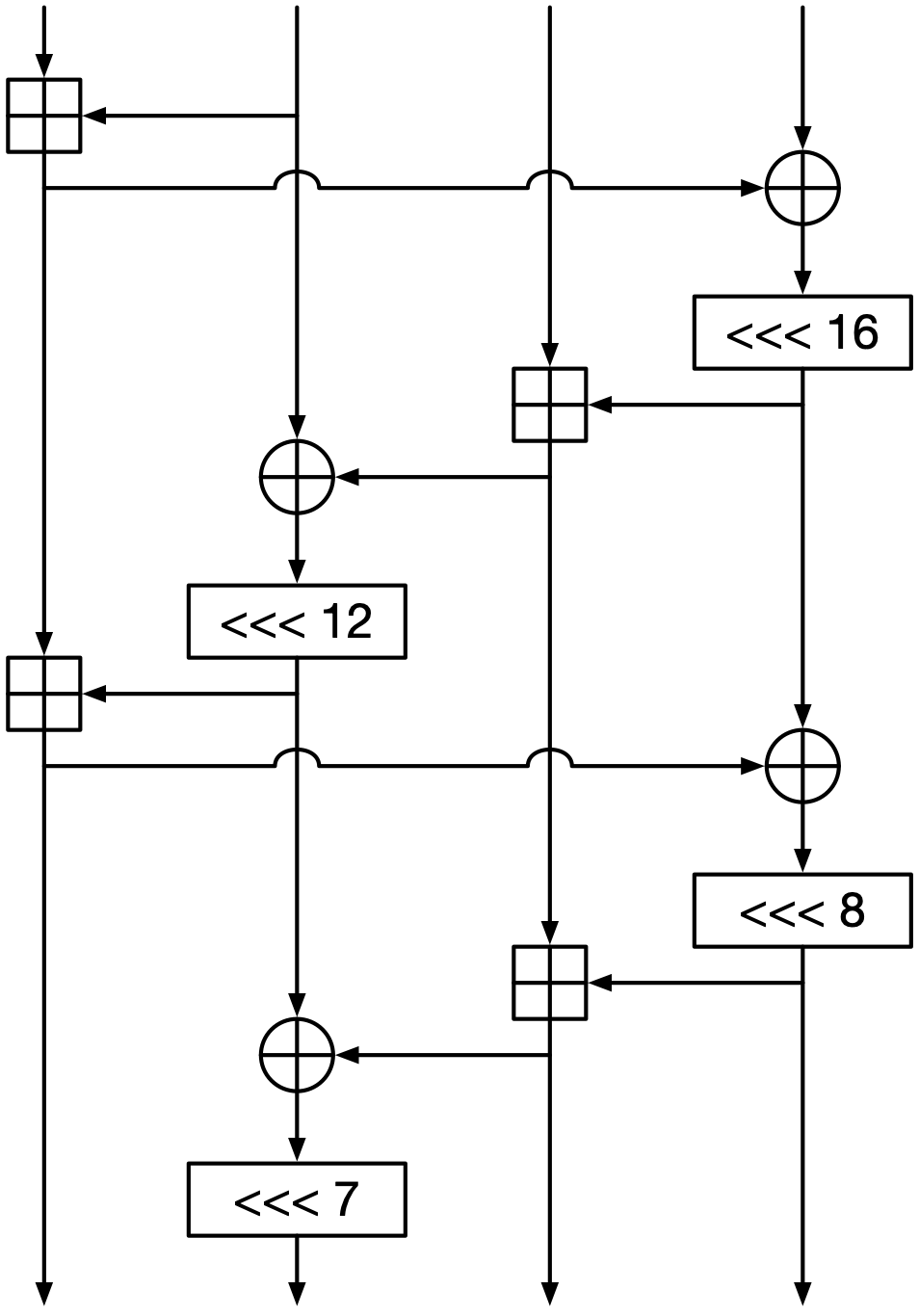

ChaCha20’s round function consist of four applications of a quarter-round function. (This is unique to ChaCha20; most algorithms don’t have quarter-rounds.) A ChaCha20 quarter-round operates on four 32-bit words, and is shown in Fig. 5. Using XOR, addition, and rotations, it thoroughly mixes the four words together.

Fig. 5 The ChaCha20 quarter-round function.#

Each line represents one 32-bit word. \(\oplus\) represents XOR, and \(\boxplus\) represents addition modulo \(2^{32}\). \(\lll n\) represents bitwise left rotation by \(n\) bits.

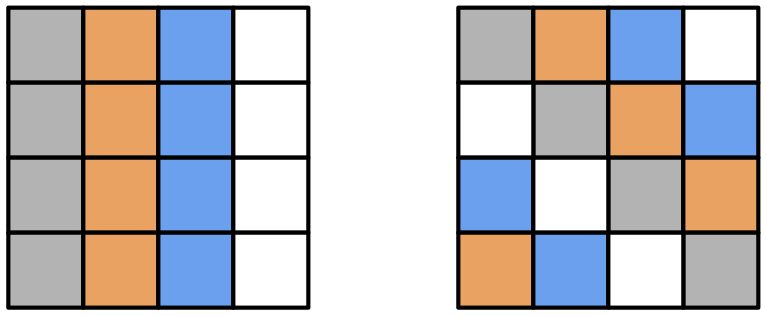

ChaCha20 actually has two different types of rounds: odd and even. The first round is odd, the second round is even, and so on. An odd round consists of doing one quarter-round on each column of the matrix. An even round consists of doing one quarter-round on diagonals of the matrix. See Fig. 6. Odd rounds therefore create confusion within each column, while even rounds create confusion across columns. (Recall the definition of confusion in this context: hiding the relationship between the ciphertext and the key.)

Fig. 6 Left: structure of a ChaCha20 odd round. Right: an even round.#

Each cell is a 32-bit word; cells of the same color are fed into the quarter-round function together.

Below is an example of generating one ChaCha20 keystream block. We use a key consisting of all zero bits, a nonce of all zero bits, and an initial counter value of 1. The matrix is thus initialized with these values:

0x61707865 0x3320646e 0x79622d32 0x6b206574

0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x00000001 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

After the first quarter-round, the matrix is as below. Notice that only the first column has changed (since that is what the first quarter-round operates on), and it has been scrambled.

0xa7877feb 0x3320646e 0x79622d32 0x6b206574

0xcafd648e 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x5b82fd4f 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0xe31e9bdf 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

After 20 full rounds, the matrix is as below, and this is what would be XORed with plaintext to encrypt, or with ciphertext to decrypt. Notice that even though the matrix started out as mostly zeroes, it is now filled with patternless nonsense.

0xbee7079f 0x7a385155 0x7c97ba98 0x0d082d73

0xa0290fcb 0x6965e348 0x3e53c612 0xed7aee32

0x7621b729 0x434ee69c 0xb03371d5 0xd539d874

0x281fed31 0x45fb0a51 0x1f0ae1ac 0x6f4d794b

It’s important to note that although the above output looks like patternless nonsense, there is no randomness in ChaCha20’s operations. Look closely at the quarter-round function: all it’s doing is XOR, addition, and rotations. For a given key, nonce, and counter, ChaCha20’s output will be exactly the same every time. That’s what enables it to work as a stream cipher.

Malleability#

The fact that the ciphertext is simply a keystream XORed with plaintext gives it a rather undesirable property. If an attacker flips a bit in the ciphertext, and you decrypt it with the right key, the result will be the original plaintext with a single flipped bit, in the same position where the attacker flipped a bit. You would have no way to tell that this happened.

This is an extremely powerful capability for an attacker to have. In practice, many plaintexts have publicly-known, highly predictable structures, which means that attackers can often know where in a plaintext some important piece of information is located. If they do, they can precisely modify it by only modifying ciphertext.

For example, consider a bank’s website. The frontend, running in the browser, might tell the server to initiate a money transfer by encrypting and sending a string like this:

from_account=11223344&to_account=55667788&amount=1000

If account numbers are always the same length, the amount always starts at the 50th byte (400th bit) of the string. (An attacker could easily find this out, simply by using the bank’s website themselves as a legitimate user.) Knowing this, an attacker could intercept the traffic of someone else using the site, and flip the 404th bit of the ciphertext. When the bank’s server decrypted the ciphertext, it would get:

from_account=11223344&to_account=55667788&amount=9000

Suddenly the transfer is for $9000, rather than $1000. Oops!

This property is called malleability: the ability of an attacker to cause precise modifications to plaintext by only modifying ciphertext. All ciphers based on XORing a keystream with plaintext are malleable. There are other types of cipher that are not malleable; we’ll see examples in later chapters.

Note, however, that manipulating a plaintext via malleability does not give the attacker any information about the plaintext or the key. It does not compromise confidentiality. It is, however, an excellent illustration of why integrity and authentication are just as important as confidentiality when you’re trying to communicate securely.

So what can we do to mitigate ChaCha20’s malleability? The answer lies in another type of algorithm. We’ll see an example in the next section.

Security#

ChaCha20 is considered highly secure, if used correctly. There is no cryptanalysis that has gotten anywhere near a concerning attack on it. It is one of two symmetric ciphers standardized for use in TLS 1.3, the newest version of the standard that secures web traffic. You should have no concerns about using it.

That said, as we’ve seen, it is quite possible to misuse ChaCha20 and thus nullify its security. Reusing a nonce with a key, or using the cipher without some means of providing integrity and authentication, is insecure.

Poly1305, a Message Authentication Code#

A message authentication code (“MAC” for short) is an algorithm that can do two things:

Signing: the inputs are a key, and any amount of data. The output is a chunk of data of a short, fixed size (128 bits is typical) called a tag. The tag has no inherent meaning, and looks like patternless garbage.

Sometimes the tag itself is called a “MAC”; to avoid confusion, we’ll call the algorithms “MACs” or “MAC algorithms”, and the outputs of those algorithms “tags”.

Verification: the inputs are a key, a tag, and any amount of data. The output is “valid” if the given tag was created with exactly the given key and data, and “invalid” otherwise.

MAC algorithms are not to be confused with digital signature algorithms, which also offer signing and verifying functionality, but with asymmetric keys. We’ll see them in a later chapter.

To be secure, MACs must be unforgeable: it must be infeasible for an attacker to produce a tag that is valid under a key they do not have. (Infeasible, not impossible: like ciphers, MACs are susceptible to brute-force attack.)

Because MACs are fundamentally different from ciphers, the cipher attack models such as “known-plaintext attacks” don’t apply. Instead, MACs have these attack models:

In known-message attacks, the attacker has a set of messages and valid tags for them, all made with the same key.

In chosen-message attacks, the attacker can choose messages and get valid tags for them, all made with the same key. In this attack model, unforgeability means that the attacker can’t produce a valid tag without querying whatever system is producing tags for their chosen messages.

MACs provide integrity and authentication, but not confidentiality. If you receive a message along with a tag, and verifying the tag succeeds, then you are assured that whoever sent the message had the exact same key and message contents that you have. If an attacker modifies either the message or the tag while they’re in transit from the sender to you, your tag verification will fail.

MACs also do not provide non-repudiation. Suppose Alice and Bob share a MAC key, and Alice uses it to sign a message. Bob can verify the tag. However, Bob cannot convince a third party that it really was Alice who signed the message, because he has possession of the same MAC key. Therefore, it could have been Bob who signed the message; a third party has no way to know.

Signing#

Poly1305 is a MAC based on doing simple math on large numbers. It produces a 128-bit tag. It was first published in 2005[Ber05] by Daniel Bernstein2The same person who designed ChaCha20. We’ll be seeing his name many more times throughout the course; he is quite a prolific cryptographer..

Poly1305 requires a 256-bit key, which it divides into two 128-bit halves. The first half is called \(r\), and it has to be adjusted before use so that some specific bits of it are zero. In total, 22 of \(r\)’s bits must be fixed in this way. The second half of the key is called \(s\), and it must be unique per-message to be secure.

Poly1305 signing works as follows:

Adjust \(r\): set the most-significant four bits of bytes 3, 7, 11, and 15 to zero, and the least-significant two bits of bytes 4, 8, and 12 to be zero.

Divide the message into 128-bit blocks. (The final block may be shorter than 128 bits, but that’s OK.)

Initialize a variable, the accumulator, to zero.

Take each message block, add a single 1-bit to the end, then interpret that as a little-endian integer. Add that integer to the accumulator. Multiply the accumulator by \(r\). Finally, reduce the accumulator modulo \(2^{130} - 5\).

After processing all of the input, add \(s\) to the accumulator.

Convert the accumulator into bytes, using the little-endian convention. The first 128 bits of the result is the tag.

Note that there is no randomness involved. That means that for a given message and key, the computed tag will always be the same. That is important for verification.

Poly1305 can be slightly tricky to implement, because it involves doing arithmetic on integers wider than 128 bits. Modern Intel processors, for example, are 64-bit, so doing arithmetic on integers wider than that requires more specialized code. However, fast implementations now exist for most types of hardware.

Verifying#

To verify a message and a Poly1305 tag, you run the signing algorithm on the message, and compare the output with the tag you’re verifying. If they’re equal, then the tag you’re verifying must have been made with the same message and key you’re using, and thus the tag is valid. Otherwise, the tag is invalid.

All common MACs work this way. They only define a procedure for signing, and the procedure for verification is to run the procedure for signing and compare its output against the tag to be verified.

There is one very subtle point in the verification procedure: comparing your computed output with the tag you’re verifying. It sounds so simple that it may seem not worth remarking on: you just see if they’re the same, right? In fact, no: the most obvious way to implement this comparison introduces a timing-based side channel.

If you had to write a function that compares two byte arrays for equality, you’d probably write something like this:

boolean insecureCompare(byte[] a, byte[] b) {

if (a.length != b.length) {

return false;

}

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

if (a[i] != b[i]) {

// Return early; we know the result will be false no matter what the

// rest of the arrays look like.

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

The important part is that as soon as the function finds two bytes that don’t match, it returns false, without looking at the bytes that come after. Why bother? After all, if it finds a mismatch, the equality comparison is false, no matter what the rest of the bytes are.

Any programming language’s standard library functionality for comparing two arrays will work like this. Outside cryptographic contexts, it’s the right thing to do: it returns the correct result, and it’s the most efficient way.

The problem is that if an attacker can precisely measure how long a system takes to verify a tag, they can gain information about where the first incorrect byte of an invalid tag is. For example, they can send the system 256 tags: each one has a different value as its first byte. One of those must have the same first byte as the real tag of the message. When verifying that one, the system will take slightly longer to fail to verify it, because the comparison loop will go through two iterations instead of just one. With precise enough measurement, the attacker can detect that timing difference, and thus learn the first byte of the real tag. Then they can repeat the same procedure for the rest of the bytes, and learn the entire tag.

This is how the comparison is done securely. The exact same amount of work is done for every element of the two arrays:

boolean secureCompare(byte[] a, byte[] b) {

if (a.length != b.length) {

return false;

}

int unequal = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

// Compare all the bytes. Don't return early.

// If a[i] == b[i], then a[i] ^ b[i] == 0 and "unequal" will be unchanged.

// If a[i] != b[i], then a[i] ^ b[i] != 0 and "unequal" will become nonzero.

unequal = unequal | (a[i] ^ b[i]);

}

// If all the bytes were equal, this will still be zero.

return unequal == 0;

}

In Java, the class java.security.MessageDigest has a static method isEqual,

which does exactly this; use that instead of writing your own.

Caution

This is another one of those minor-seeming mistakes that can be disproportionately damaging to security. This particular mistake is one of the easiest ones to make.

ChaCha20-Poly1305, an AEAD scheme#

Stream ciphers’ malleability can be neutralized by using the cipher in conjunction with a MAC. That way, any modification of the ciphertext by an attacker will cause a MAC verification failure, letting the recipient of the ciphertext know that something is amiss. This combination is called authenticated encryption, providing confidentiality, integrity, and authentication.

In the real world, ChaCha20 and Poly1305 are almost invariably used together, in a scheme called ChaCha20-Poly1305. The combined scheme is an example of authenticated encryption with associated data, or AEAD for short.

An AEAD scheme encrypts and authenticates a message, and can optionally authenticate some other data that does not get encrypted. Such data is called the additional authenticated data, or AAD for short. In practice, applications that use AEAD schemes will input some metadata about the message as AAD, and they may or may not send the unencrypted AAD along with the message.

The two operations of an AEAD are sometimes called sealing (encrypting and signing) and opening (verifying and decrypting), by analogy to an envelope.

Order of Operations#

The notion of “combining” ChaCha20 and Poly1305, or “using them together”, is all well and good, but it’s missing crucial details. What do you actually give to Poly1305, the MAC, as input, and what do you do with the tag?

This question took a surprisingly long time to be settled in the cryptographic community. There are three alternatives, all of which have been used by major real-world cryptographic protocols.

Encrypt-and-MAC. That is, encrypt the plaintext, sign the plaintext, and append the tag to the ciphertext. SSH, the Secure Shell protocol, does this.

MAC-then-encrypt. That is, sign the plaintext, append the tag to the plaintext, then encrypt them together. TLS, the protocol that secures web traffic, does this.

Encrypt-then-MAC. That is, encrypt the plaintext, sign the ciphertext, and append the tag to the ciphertext. IPsec, a popular suite of protocols for VPNs, does this.

Option 3 is now known to be the correct one, even though it may seem unintuitive. The key advantage it offers is that when you receive a message, you can verify the tag before decrypting anything. This is advantageous for two reasons. One, for performance: if an attacker is flooding your system with tampered ciphertext, this will allow you to discard it without decrypting or otherwise processing it, which saves time. Two, for security: it avoids exposing your cipher to tampered ciphertext, thus reducing the attack surface of your system. This isn’t a major concern for stream ciphers, but once we move on to block ciphers, we’ll see a way in which exposing a block cipher to tampered ciphertext can expose a serious side channel. The fact that TLS doesn’t use option 3 has left it vulnerable to many well-known attacks. This has been called the Cryptographic Doom Principle[Mar11]:

If you have to perform any cryptographic operation before verifying the MAC on a message you’ve received, it will somehow inevitably lead to doom.

Under option 3, any ciphertext tampering will result in a MAC verification failure. Option 3 is also secure in a more theoretical sense, under weak assumptions about the security of the encryption and MAC algorithms[Kra01].

Options 1 and 2 have been used in very widely-used cryptographic protocols, but that is a relic of a time when we knew less about cryptography than we do now. New designs should always use option 3.

Details#

With that settled, there is only one question left to answer regarding how to put ChaCha20 and Poly1305 together: how are the algorithms keyed?

Recall that ChaCha20 and Poly1305 each take a 256-bit key. One option would be to say that the combination of the two as an AEAD takes a 512-bit key, and use half for ChaCha20 and half for Poly1305. Instead, though, the AEAD only takes a 256-bit key. It uses that key directly for ChaCha20, and uses part of the ChaCha20 keystream as the key for Poly1305.

Finally, then, ChaCha20-Poly1305 sealing works as follows. It takes as input a plaintext, optional AAD, a 256-bit key, and a 96-bit nonce.

Using ChaCha20 with the 256-bit key, a block counter of 0, and the 96-bit nonce, generate one 512-bit keystream block. Save the first 256 bits of this for later use with Poly1305; discard the rest.

Encrypt the plaintext with ChaCha20, using the same key and nonce as in step 1, but starting the block counter at 1.

Form the input to Poly1305 as follows: the AAD (if any), followed by the ciphertext, followed by the byte length of the AAD as a 64-bit integer, followed by the byte length of the ciphertext as a 64-bit integer.

Sign the data from step 3, using Poly1305 with the saved half of the keystream block from step 1 as the key.

The output is the ciphertext from step 2 and the tag from step 4.

ChaCha20-Poly1305 opening works as follows. It takes as input a ciphertext, optional AAD, a 128-bit tag, a 256-bit key, and a 96-bit nonce.

Perform step 1 from the sealing process to compute the Poly1305 key.

Form the input to Poly1305 by performing step 3 from the sealing process.

Sign the data from step 3, using Poly1305 with the saved half of the keystream block from step 1 as the key. If this tag matches the input tag, proceed to step 4; if it doesn’t match, report failure, terminate the opening process, and do not decrypt the ciphertext.

Decrypt the ciphertext with ChaCha20, using the same key and nonce as in step 1, but starting the block counter at 1.

Key Takeaways#

The repeating-key XOR cipher and one-time pad are both unusable in practice, but the mechanism of XORing plaintext with random-looking bytes is useful.

A stream cipher is an algorithm that derives an arbitrarily-long, random-looking keystream from a fixed-length key.

Stream ciphers require a nonce as input. You must never reuse a nonce with the same key, or else even a good stream cipher degrades into being the repeating-key XOR cipher.

Stream ciphers, by themselves, are malleable: an attacker can precisely modify plaintext by only modifying ciphertext. Messages must be authenticated to neutralize this problem.

ChaCha20 is a stream cipher that takes a 256-bit key. It is considered very secure and is widely used in the real world. By itself, it only provides confidentiality.

A message authentication code is an algorithm that produces a small, fixed-length tag from a key and a message, and that can verify whether a given tag was made using a given key and message. Attackers should not be able to produce a valid tag for a message without having the key being used to verify.

Poly1305 is a message authentication code, taking a 256-bit key and producing a 128-bit tag. By itself, it only provides integrity and authentication.

Comparing two tags for equality must be done carefully, to avoid creating an exploitable side channel.

When encrypting and authenticating a message, the input to the MAC should be the ciphertext, not the plaintext.

ChaCha20-Poly1305 is an AEAD scheme: a way of using a cipher and MAC together to provide confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. This combination is authenticated encryption. An AEAD can also authenticate additional data that does not get encrypted.