RSA#

RSA is an asymmetric-key cipher — the only one in widespread use, and the first to be publicized. It can also work as a signature algorithm. We are devoting an entire chapter to it because of its importance.

At its core, RSA is a very simple algorithm, but it is very, very easy to get wrong. It is unmatched among commonly used algorithms in the sheer number and variety of ways in which its security can fail[Bon99]. It is such a minefield of problems that experts increasingly recommend avoiding it altogether.

One quick note is that in addition to RSA the algorithm, there is also a computer-security company called RSA Security. They are related in that the algorithm’s three designers are also the company’s cofounders: Ron Rivest1He of MD5, RC4, and RC6 fame., Adi Shamir2One of the two who made the public rediscovery of differential cryptanalysis., and Len Adleman. Any time you see “RSA” in this course, it means the algorithm; we’ll refer to the company as “RSA Security”.

Algorithm#

Like the asymmetric-key algorithms we saw in the last chapter, RSA relies on a one-way function. RSA’s one-way function is integer factorization. Given two large prime numbers, it takes relatively little computation to multiply them together. Given the product of two large prime numbers, it takes a huge amount of computation to factorize it: to compute what those two prime numbers are.

To generate a key pair:

Randomly generate two large prime numbers of similar size, \(p\) and \(q\). (We will see how to do this later.) Compute \(n \leftarrow p\times q\).

Choose a number, \(e\). It must be relatively prime to \((p-1)\times (q-1)\). In practice, RSA implementations use one of three hardcoded values: 3, 17, or 65537 (which are all prime), and make sure that \(e\) does not divide \(p-1\) or \(q-1\).

Note that there are multiple attacks that are easier if \(e=3\), so that shouldn’t be used anymore; secure implementations use 65537.

Compute \(d \leftarrow e^{-1} \pmod{(p-1)\times (q-1)}\) using the extended Euclidean algorithm. We know this inverse exists because \(e\) is relatively prime to \((p-1)\times (q-1)\).

\(e\) and \(n\), collectively, are the public key. \(d\) is the private key.

We call \(e\) the public exponent, and \(d\) the private exponent. \(n\) is the public modulus, or just “modulus”.

To encrypt and decrypt a message, we must express the message as a number less than \(n\). We will look at how that’s done in practice later. For now, let’s call this number \(m\).

The sender computes \(c \leftarrow m^e \Mod n\), where \(e\) and \(n\) are the recipient’s public key. \(c\) is the ciphertext.

The recipient computes \(c^d \Mod n\), where \(d\) is the recipient’s private key. This is equal to \(m\).

That’s the whole algorithm. Let’s go through an example.

\(p = 97\) and \(q = 47\). Therefore \(n = 4559\).

We’ll use \(e = 17\), having made sure that 17 does not divide 96 or 46.

Compute the multiplicative inverse of 17 modulo 4416 (which is \(96 \times 46\)). The result is \(d=3377\).

Let’s encrypt the message \(m = 3048\). Using modular exponentiation, we compute \(3048^{17} \Mod 4559 = 3707\). This is the ciphertext.

To decrypt, we compute \(3707^{3377} \Mod 4559\). This works out to 3048, the original \(m\).

RSA can be used as a signature algorithm by simply using the keys in the opposite order. To sign a message \(m\), the signer uses their private key to compute \(s \leftarrow m^d \Mod n\). The verifier uses the signer’s public key to compute \(s^e \Mod n\), and checks that the result is equal to \(m\).

The “key size” of RSA is the length, in bits, of the modulus \(n\). The moduli used by RSA in the real world are enormous. The current recommendation is that moduli should be at least 2048 bits long, which is about 616 decimal digits. 4096-bit moduli are not uncommon. To generate a modulus of \(n\) bits, each prime factor must be \(n/2\) bits long.

Number Theory#

It seems entirely unintuitive that the above algorithm should work; that is, that those two modular exponentiations should result in the original plaintext. You can find the full proof of RSA’s correctness in the Mathematical Details appendix.

Integer Factorization#

The theoretical security of RSA rests on the fact that there is no way to compute \(d\) from \(e\) and \(n\) without knowing \(p\) and \(q\); that is, without knowing the prime factors of \(n\).

Finding the prime factors of \(n\) is easy in the sense that there’s an obvious way to do it (trial division: try dividing it by every number up to \(\sqrt{n}\)). However, it’s hard in the sense that there is no known way to do it in a reasonable amount of time, for numbers that are the size of RSA moduli, and that have only two equal-sized prime factors. (Such a number, with only two prime factors that are of equal size, is called a semiprime.)

RSA Security had a public challenge running from 1991 to 2007, in which they published semiprimes of various sizes, and offered cash prizes for their factorizations. (The company did not know the factorizations — they destroyed the computers they used to generate the numbers after extracting the semiprimes.) The largest semiprime ever factorized was one of these challenge numbers. It’s called RSA-250 and has 250 decimal digits (829 bits). The factorization was completed in February 2020, and took a few months. Cryptographers had recommended avoiding 1024-bit moduli (formerly a common size) long before RSA-250 was factorized, but the result underscored the urgency of the recommendation. RSA moduli should now be at least 2048 bits.

The current best general-purpose factorization algorithm is called the general number field sieve (GNFS). It was used to factorize RSA-250 and several other RSA challenge numbers. The qualifier “general-purpose” means that its performance does not depend on the specific form of the number to be factorized (like how many prime factors it has, or how large they are), but only on the size of the number itself. The details of GNFS are beyond our scope here, but it’s important to know that a large part of it is easily parallelizable. That means that it can be sped up by using more computers, not just by using faster computers.

Quantum computing

If you read any discussion of the state of the art in factorization, you’ll inevitably come across a mention of quantum computing, usually described as a looming threat to the security of cryptography as we know it. If it becomes practical, then it will indeed be a major paradigm shift in computing[dW17], but that’s a big “if”.

The details of quantum computing are far beyond the scope of this course, but this is the basic idea. It replaces the classical-computing notion of bits with qubits. Bits are always in one of two states: 0 or 1. Qubits can be (very roughly speaking) both at the same time, until they are measured, at which point they “collapse” to one or the other with certain controllable probabilities. There are also quantum equivalents of classical logic gates (like AND and OR) that operate on qubits. The idea (again, very roughly) is that a quantum computer can do the equivalent of many classical computations simultaneously, using this controllable uncertainty of qubit values. If you’re interested in a much more in-depth explanation of quantum computing, see here.

There are various physical implementations of qubits, such as the polarization of a photon, or the spin of an electron. Maintaining even a single qubit requires an enormous amount of specialized hardware and very tightly controlled conditions (e.g. temperatures very close to absolute zero). Even under the best conditions, qubits and quantum logic gates suffer from errors due to interference from the environment and each other, which severely limits the size of the quantum circuits that can be reliably used.

There are quantum algorithms for factorization: one from 1994 called Shor’s algorithm[Sho94] and a variation from 2023 called Regev’s algorithm[Reg24]. With enough qubits, they would be able to factorize current RSA moduli within a reasonable amount of time. However, quantum computers are currently very far from being able to work on numbers of that size. The largest number that either algorithm has factorized so far is — no joke — 21. A team at IBM has tried to factorize 35, but it failed because of accumulating errors.

The engineering of quantum computers will certainly improve, so there is active research into designing quantum-resistant public-key algorithms. (Existing symmetric-key algorithms are basically fine already.) However, it may be that it’s physically impossible to build a quantum computer big enough to factorize RSA numbers. No one knows yet; we’re not even close to knowing.

The bottom line is that, in practice, this just isn’t something worth worrying about yet. RSA already has plenty of security problems here in the classical-computing world!

Primality Testing#

It is very important to note that the task of determining whether a number is prime is very different from that of finding a number’s factors. The former task can be done with much, much less computation. If it weren’t for this, RSA would be impossible: there would be no way to make an \(n\) too big to factorize without having \(p\) and \(q\) too big to test for primality.

The two most commonly-used primality tests for RSA key generation are probabilistic algorithms. That is, they return an answer that is correct with some probability less than 1. Generally the algorithm has some way to raise that probability, at the cost of more computation, until it is as close to 1 as you want it to be. The two algorithms we’ll look at have two possible outputs for a given input: “definitely composite” and “probably prime”.

The first one is the Fermat test. There is a theorem in number theory called Fermat’s Little Theorem, which states that if \(n\) is prime and \(a \neq 0\), then \(a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\). (We won’t prove this here, but the proof is in the appendix.) The Fermat primality test uses this theorem. For an input \(n\), it picks various values of \(a\) and computes \(a^{n-1} \Mod n\). If the result is not 1, \(n\) is definitely composite. If the result is 1, \(n\) is probably prime.

The reason why the test can’t return a “definitely prime” result is that the congruence \(a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\) is actually true for some composite values of \(n\), and some values of \(a\). For example, let’s test the number 5461, using \(a = 2\):

That indicates that 5461 is “probably prime”. However, 5461 is actually composite. This can be discovered by repeating the Fermat test with a different value of \(a\), in this case 3:

That indicates that 5461 is definitely composite. It’s important to note that this result does not give you any information about the prime factors of \(n\). You just know it’s not prime.

To reduce the probability that a composite number will slip past the Fermat test, the test is repeated many times, with different values of \(a\). By doing so, you can reduce that probability extremely low, but never all the way to zero.

The second primality test is the Miller-Rabin test. It’s similar to the Fermat test, but with an additional criterion; we won’t go into detail here. Like the Fermat test, it involves picking a number \(a\) and raising it to a power modulo \(n\), and each value of \(a\) can show that \(n\) is definitely composite or probably prime. Repeating the test with different values of \(a\) increases the probability that the result is correct.

In practice, most implementations of RSA prime generation will test a number for primality first by trial division with the thousand or so smallest primes (of which they have a hardcoded list) and then run the Miller-Rabin test several times. They generally run Miller-Rabin enough times to make the probability of returning a composite number 1 in \(2^{128}\), which is zero for all practical purposes.

There does exist a primality testing algorithm that returns definite results, called the AKS primality test. The discovery of this algorithm in 2002 was a major breakthrough in theoretical computer science: previously, no one knew whether such an algorithm even existed. In practice, though, AKS isn’t used when generating RSA primes. Although it’s efficient, it is slower than Miller-Rabin, and the uncertainty involved in Miller-Rabin is not a problem.

Forming the Message#

In the above description of RSA, we deferred the question of how to convert a message — which, in practice, is a string of bytes — into a number that you can raise to a power.

The obvious, but wrong, answer is to simply treat the bytes as parts of a single

number. For example, if we encode the string cipher in ASCII, we get the bytes (in hex):

63 69 70 68 65 72. Then we can use the number 0x636970686572 as \(m\) in the

RSA algorithm.

Do not do this! There are several problems with it:

The first serious problem is that encrypting a message \(m\) with the same key always produces the same ciphertext (whether the key is the private or public part), because there is no randomness in RSA encryption. This is the same problem as we saw with block ciphers in ECB mode.

Another problem arises when encrypting the same message with multiple different keys. If there are \(e\) public keys that have different moduli but all use \(e\) as the public exponent, then if an attacker gets the ciphertexts of the same message encrypted under all \(e\) of those keys, they can easily recover the message. (This makes use of a theorem called the Chinese Remainder Theorem, which we won’t go into here.) Since many RSA implementations use the values 3 and 17 for \(e\), this attack can be practical.

Yet another problem is that if \(m\) is small and \(e\) is small, it may be that \(m^e < n\), meaning that \(m^e \Mod n\) is just \(m^e\). That would mean an attacker could easily recover the plaintext from the ciphertext by taking the \(e\)-th root of it.

Finally, RSA encryption is malleable. We saw this property in the context of stream ciphers, but in the case of RSA, the combining operation is multiplication instead of XOR. If you encrypt plaintexts \(m_1\) and \(m_2\), you can multiply the ciphertexts together to get a result that is the same as the ciphertext of the plaintext \(m_1 \times m_2\).

This opens the possibility of a chosen-ciphertext attack. Suppose an attacker has the ciphertext, \(c\), of a plaintext \(m\). If they can convince a target system to decrypt the ciphertext \(k^e \times c\) and return the plaintext3This can be a practical attack: some systems, upon encountering a decrypted plaintext that they do not understand, will dump that plaintext verbatim in an error message that the attacker sees., they can multiply that plaintext by \(k^{-1} \Mod n\) to get \(m\).

All of these problems indicate that simply treating a message’s bytes as a number is not a secure way to use RSA. There are two schemes for constructing a message to avoid these problems, both of which are called padding. I consider that a misnomer: they aren’t merely adjusting the message’s length, but imparting security as well.

Before we cover padding, there’s one other important fact to note: \(m\) must be less than \(n\), the modulus. Because the results of encryption and decryption are reduced modulo \(n\), they cannot be greater than or equal to \(n\). You can encrypt an \(m\) that is greater than \(n\), but the result of decryption will be a different number. It will be congruent to \(m\) modulo \(n\), but not the same number.

This fact, along with RSA’s very slow performance compared to symmetric-key ciphers, it means that RSA is not used to encrypt large amounts of data. If you had a lot of data that you needed to “encrypt with a public key”, you would randomly generate an AES key, use it to encrypt the data with AES, then encrypt the AES key with RSA and send both ciphertexts to the recipient4Ideally, you would not do that either: you would run ECDH with the recipient to agree on an AES key, and not involve RSA at all.. To sign a large amount of data, you sign a hash of the data instead of the data itself — recall that signing with RSA is just encryption using the private key.

PKCS#1 v1.5 Padding#

At the outset: this padding scheme is insecure and you should not use it if you have a choice! We’re covering it here to show how it’s insecure, and because despite all its problems, it’s still extremely commonly used in practice. (Your browser used it while loading this page!)

This padding scheme comes from version 1.5 of a standard called PKCS#1. It is used for both encryption and signing, though it differs slightly in those two contexts.

For encryption, the scheme works as follows, for a message \(m\) that is \(\ell_m\) bytes long:

Create a byte array of the same size as the modulus.

Set the first (leftmost) byte to

0x00, and the second byte to0x02.Set the rightmost \(\ell_m\) bytes of the byte array to \(m\), the message.

Set the byte immediately to the left of the message to

0x00.Set the bytes between the second byte and the zero byte from step 4 to randomly-generated nonzero values.

Treat the byte array as a big-endian number. This number is the plaintext.

To unpad after decryption, verify that the first two bytes are 0x00 0x02, then

find the next zero byte. Everything after it is the message.

This solves the problems identified above. It introduces randomness into the plaintext, so that the same message will not encrypt to the same ciphertext every time. It makes the plaintext a large enough number that raising it to the power of 3 will make it greater than \(n\). And it eliminates the multiplication-based malleability.

For signing, the scheme is the same, except in step 5:

Create a byte array of the same size as the modulus.

Set the first byte to

0x00, and the second byte to0x01.Set the rightmost \(\ell_m\) bytes to \(m\), the message (which, in practice, is a hash).

Set the byte immediately to the left of the message to

0x00.Set the bytes between the second byte and the zero byte from step 4 to

0xFF.Treat the byte array as a big-endian number. This number is the plaintext, to be exponentiated by the signer’s private key.

To verify the signature after exponentiating it by the signer’s public key, the verifier should independently go through the above process to create the expected plaintext, then compare it to the actual plaintext byte-by-byte.

Note that there is no randomness in the padding for signatures, which is why a verifier can reconstruct it exactly. There’s no need for randomness in signatures, because the message being signed is publicly known anyway; the plaintext recovery attacks on no-padding RSA are not a concern.

There are several attacks on PKCS#1 v1.5 padding, which we will see in a later section.

OAEP and PSS#

These two padding schemes are currently recommended for any usage of RSA. Both were developed by Mihir Bellare and Phillip Rogaway. OAEP stands for Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding and is used for RSA encryption, and PSS stands for Probabilistic Signature Scheme and is used for RSA signatures. OAEP and PSS are structurally similar, so we’ll look at them together.

Note that the two schemes were standardized together, in a later version of PKCS#1 called PKCS#1 v2.0. This can get confusing, so we’ll only refer to them as OAEP and PSS (they were published in the literature under those names before PKCS#1 was revised to include them).

Both schemes require the use of a hash function. The communicating parties must agree on a hash function first. Throughout the description, we will refer to the chosen hash function as \(H\).

Both schemes use a primitive called a mask generation function, which behaves like a hash function5That is: variable-length input, deterministic, collision-resistant, preimage-resistant. with a variable-length output. The current RSA standard specifies a way of constructing a mask generation function from any hash function. The details aren’t necessary here; it consists of repeatedly hashing the input along with an incrementing counter, until the desired amount of output has been produced.

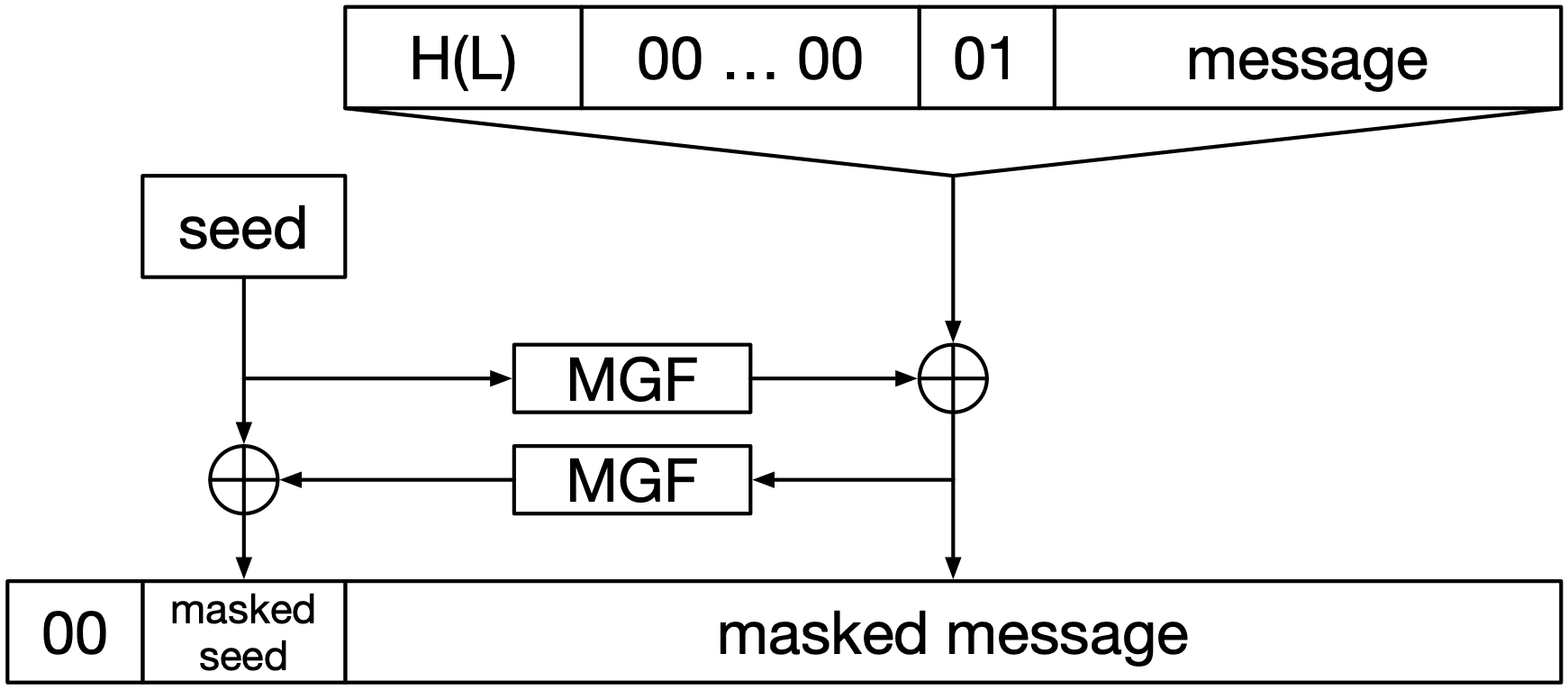

Fig. 18 OAEP. The inputs are message and \(L\). The output is at the bottom.#

See Fig. 18 for a diagram of OAEP.

The byte array at the bottom is interpreted as a number and used as the input to RSA encryption. The length of that byte array is the same as the length of the RSA modulus. Looking at the individual components:

00at the bottom, and01at the top, are fixed bytes of those specific values.seedis a randomly generated bit string of the same length as \(H\)’s output.\(L\) is a label, some additional data to be associated with the message but not encrypted. \(H(L)\) is the hash of it. \(L\) can be empty.

00 ... 00represents a string of as many zero bytes as necessary to make the overall output have the right length. Its length is the modulus length, minus twice the hash length (forseedand \(H(L)\)), minus the message length, minus two (for the two fixed0x00and0x01bytes). It may be empty.The output lengths of the two usages of the mask generation function (the

MGFboxes) are set to the same length as the strings their outputs are XORed with. The upperMGFis set to produce an output of the same length as \(H(L) || \texttt{00 ... 00} || \texttt{01} || \texttt{message}\). The lowerMGFis set to produce an output of the same length as the seed.

Undoing OAEP is relatively straightforward. The lengths of the masked seed and

masked message are known, so the decryptor can find them in the decrypted

output. The seed can be recovered by XORing the masked seed with

MGF(masked message). The message can then be recovered by XORing the masked

message with MGF(seed).

PSS is only used for signatures. It optionally includes a random element called the salt, which is a string of randomly-generated bytes of length \(\ell_s\) (which can be zero). Its total output length is the same as the length of the RSA modulus.

It works as follows:

Hash the message to get \(H(M)\).

Construct a string of eight

0x00bytes, followed by \(H(M)\), followed by the salt. Hash this string and call the result \(H(M')\).Construct a string of zero or more

0x00bytes, followed by a single0x01byte, followed by the salt. The number of0x00bytes at the beginning should be set so that the length of the overall string is the total length of the output, minus the hash length, minus one. Call this stringDB.XOR

DBwithMGF\((H(M'))\) (setting the output length ofMGFto the length ofDB). This is “maskedDB”.The output is the masked

DB, followed by \(H(M')\), followed by the single fixed byte0xBC.

To verify a signature, the verifier separates the three components of the

output, which it can do because it knows the length of \(H(M')\). It recovers DB

and thus recovers the salt. Then it computes \(H(M')\) independently and compares

it with the purported \(H(M')\) from the signature.

OAEP and PSS were specifically designed to avoid the weaknesses of PKCS#1 v1.5. They add randomness to the input, and they have a more complex structure. They’re generally considered as secure as RSA itself, so if you must use RSA, use these.

Vulnerabilities and Attacks#

In the Forming the Message section, we got a glimpse at the range of potential problems in RSA. We’ll see a lot more problems here, many of which have led to practical exploits.

The subtlety of some of these problems interacts poorly with the apparent simplicity of RSA. It’s quite easy to write an implementation that returns correct results for encryption and decryption: you could write the whole thing in about 50 lines of Java. That seems to encourage a lot of developers to actually do so, and to use that code in real systems. The same implementation mistakes get deployed and exploited, again and again, showing that the software industry as a whole is somewhat resistant to learning lessons about RSA.

I say often that you shouldn’t write your own cryptographic code, but it bears repeating here, because RSA can be so tempting. Just Say No to RSA!

Key Generation#

The trouble starts with generating the numbers that RSA uses as keys.

Recall that key generation for symmetric ciphers and MACs is very simple: just randomly generate some bits. Key generation for Diffie-Hellman, DSA, and their elliptic-curve variants is almost as simple: randomly generate one number for the private key, then do one modular exponentiation or point multiplication to get the public key.

RSA, by contrast, has requirements for its keys that are rather difficult to satisfy.

First of all, primes used for RSA keys must be globally unique. If a prime is ever reused between two moduli \(n_1\) and \(n_2\), it can easily be found by computing \(\gcd(n_1, n_2)\). RSA primes are large enough that generating them randomly with a well-functioning CSPRNG is vanishingly unlikely to result in repeats. That means this shouldn’t be a problem in practice, but in fact it is[HDWH12]! 6I highly recommend that paper. It’s both fascinating and horrifying: the researchers recovered 66,540 RSA private keys because of reused primes, with a few days’ worth of scanning the Internet and a few hours of computation. They also recovered DSA private keys from reused nonces.

Furthermore, there exist efficient factorization algorithms for when the prime factors of \(n\) meet specific conditions:

If one of the factors (say \(p\)) is such that \(p+1\) has only small prime factors, there is an algorithm called Williams’ \(p+1\) algorithm that can factorize \(n\) efficiently.

If one of the factors (say \(p\)) is such that \(p-1\) has only small prime factors, there is another algorithm called Pollard’s \(p-1\) algorithm that can factorize \(n\) efficiently.

This and the above problem mean that RSA key generation implementations have to check \(p-1\) and \(p+1\) to make sure they each have at least one large prime factor (100 bits or so).

To foil Pollard’s \(p-1\) algorithm, some RSA key generators try to choose primes that are of the form \(2p+1\), where \(p\) is also prime. A prime number \(p\) such that \(2p+1\) is also prime is called a Sophie Germain prime, after the mathematician who first studied them. However, key generators that use Sophie Germain primes still have to check \(p+1\) for large prime factors.

If the two prime factors of \(n\) are too close together, then \(n\) can be efficiently factorized using the Fermat factorization method. This method works from the observation that \(a^2 - b^2 = (a+b)(a-b)\), and so if \(n\) can be expressed as the difference of two squares, it is easily factorizable using that representation.

The method starts by guessing \(a\) as \(\sqrt{n}\) rounded up, then computes \(d \leftarrow a^2 - n\). If \(d\) is not a perfect square, add 1 to \(a\) and try again. If \(d\) is a perfect square, we’ve found a difference-of-squares representation: \(b = \sqrt{d}\), and \(n = a^2 - b^2\). We compute \(\gcd(n, a + b)\) and \(\gcd(n, a - b)\). If either of these yields a number greater than 1 and less than \(n\), we’ve factorized \(n\).

If \(|p-q|\) is large, this is not a concern; Fermat’s method will take an infeasibly long time7The general number field sieve, which we mentioned in the Key Generation section, is also fundamentally based on finding a difference-of-squares representation of \(n\). It uses advanced math to optimize the search for \(a\) and \(b\)..

RSA moduli vulnerable in this way were found in the wild very recently, by Hanno Böck[Boc22].

These constraints make RSA key generation time-consuming. There is no quick way to generate primes of the requisite form, and due to the global uniqueness requirement, there is no shortcut like the named curves of elliptic curve cryptography. You simply have to generate huge numbers and test them for primality, over and over and over.

There have been attempts to make shortcuts, for use by constrained computing environments like smart cards, and at least one has led to disaster; this was called the ROCA attack[NSS+17], published in 2017 by Matus Nemec et al. (The name is short for “Return of Coppersmith’s Attack”, because it was a pretty simple re-application of another attack that had been around for much longer: yet another lesson that wasn’t learned.)

The ROCA attack targeted an RSA implementation on certain smart cards. The researchers found that it only generated primes of the form \(kM + (65537^a \Mod M)\). \(M\) is a constant: the product of the first hundred or so primes. The ROCA attack includes a very quick test to identify RSA moduli that result from primes of this form, as well as a relatively fast way to factorize these moduli. The researchers were able to factorize a 1024-bit modulus in 97.1 CPU-days8A CPU-day is the equivalent computational effort of running a particular CPU for one day. The CPU the researchers chose to benchmark was an Intel Xeon E5 at 3GHz (this was done in 2017)., which is well within the realm of practicality.

The fact that the attack targeted smart cards made it particularly devastating, because it is difficult or impossible to deploy a new version of the RSA implementation to all the affected smart cards. The keys on the deployed cards also secure some critical information; for example, the country of Estonia issues smart cards to its citizens as national ID cards, and over half of them were found to be vulnerable to this attack.

Attacks on Padding#

As we saw, RSA without padding is utterly broken. However, padding doesn’t make RSA secure by itself. The structure added by padding, as well as side channels created by padding verifiers, can also open up attacks.

Some implementations of PKCS#1 v1.5 signature verification work by parsing the padded message from left to right, instead of independently constructing a padded message on their own and comparing to the purported signature. In particular, they look for the leading

0x00and0x01bytes, then any number of0xFFbytes, then0x00, and then assume the hash comes immediately after.The problem is that this strategy does not check that the hash occupies the rightmost bytes of the padded message. Any bytes after the hash are ignored. This means that there is a huge number of possible plaintexts that would be accepted as having valid padding, when there should only be one. If the public exponent is 3, this leads to a completely practical attack: the attacker constructs a padded message that looks valid in the leftmost bits, and uses the freedom to set the rightmost bits to make the message a perfect cube; the cube root of that message is a forged signature.

Another attack on PKCS#1 v1.5 is Bleichenbacher’s padding oracle attack, which exploits a padding oracle (much like the CBC padding oracle) to recover encrypted plaintext[Ble98]. This has been demonstrated in the real world many times, and new instances keep coming up, even though this attack was first discovered in 1998. The modern version of the attack is called ROBOT (Return of Bleichenbacher’s Oracle Threat)[BSY18].

This attack makes use of the fact that if an attacker knows that a ciphertext decrypts to a plaintext with valid PKCS#1 v1.5 padding, they know certain things about the plaintext: the first two bytes are

0x00 0x02, and there is at least one0x00byte later on. (If they know that the message inside the padding is a hash, they know the precise location of that0x00byte.) The attack entails calling the oracle for a large number of chosen ciphertexts, narrowing down the possibilities for what the message is.In the real world, the oracle in this attack is usually a differential fault side channel: the system doing the decryption returns different errors when the padding is invalid, versus when something else goes wrong.

In 2000, Jean-Sébastien Coron et al. published an attack[CJNP00] against PKCS#1 v1.5. It is a chosen-plaintext attack that works on low public exponents like 3, and messages that end in a run of zero bits (the more zero bits, the more likely the attack is to work). This works because PKCS#1 v1.5 places the message, unmodified, in the least-significant bytes of the plaintext. The presence of a long run of zero bits at the least-significant end means that the plaintext is, numerically, a power of two; this leads to an exploitable way of representing the plaintext. The attack boils down to factorizing a number with (hopefully) small prime factors.

Even OAEP is not safe. In 2001, James Manger published a padding oracle attack that works on OAEP[Man01]. Recall that the first byte of any valid OAEP-padded plaintext is

0x00. This attack only needs an oracle that returns whether the first byte of the plaintext is zero; it can use this knowledge to recover a plaintext. The flow of the attack is much like Bleichenbacher’s attack: use the information about a plaintext gained from knowing its first byte to gradually narrow down the possibilities for what the message is.

Fun fact: despite PKCS#1 v1.5 being so insecure, it is still used all over the place. RSA signatures on TLS certificates still use it.

Timing Attacks#

We’ve noted elsewhere in this chapter that RSA is slow, both to encrypt/decrypt and to generate keys. Whenever you hear that a cryptographic algorithm is slow, you should think, “timing attack!”

The time taken by RSA’s basic operations is heavily dependent on the inputs to those operations9This is generally not the case for the kinds of operations used in symmetric ciphers. The time it takes to XOR two words together, for example, does not depend on the values of those words.. As one example, the simplest algorithm for modular exponentiation takes different amounts of time based on the number of 1-bits in the exponent. Precise timing measurement during decryption or signing can thus reveal information about the private key.

Embedded systems like smart cards (like the Estonian ID cards from the ROCA attack) are especially vulnerable to this: their processors are slow, and attackers have extensive access to do fine-grained timing. However, that’s not the only context in which timing attacks can work. In 2003, David Brumley and Dan Boneh demonstrated a practical timing attack against the RSA implementation in the widely-used OpenSSL library, successfully exploiting it over a network[BB03]. The speed of modern processors and complexity of modern networks has diminished the practical effectiveness of this attack, but it’s still not to be ignored. In 2009, Scott Crosby, Dan Wallach, and Rudolf Riedi presented ways of compensating for the network’s timing effects to make measurements with tens-of-microseconds resolution over the Internet[CWR09].

Finally, note that timing analysis can be the mechanism that underlies a padding oracle. An example might be a server that first verifies padding, then goes on to do some time-consuming operation only if the padding is valid.

Key Takeaways#

RSA is an asymmetric-key cipher. If used properly, it is secure, but it is very, very difficult to use properly. Expert consensus is increasingly moving towards avoiding RSA altogether, but it is still very widely used.

RSA can be used for confidentiality, by encrypting with a public key and decrypting with a private key. It can also be used for authentication, by encrypting (i.e. signing) with a private key and decrypting (i.e. verifying a signature) with a public key.

RSA keys are just large integers. RSA’s “key size” is the length of one of those integers, the modulus, which is part of the public key. 2048 bits is the minimum secure key length; 4096 bits should be used if possible.

RSA’s security is theoretically based on the difficulty of finding the prime factors of a semiprime (a number with only two prime factors, of similar size). There is no known algorithm to do so efficiently.

By contrast, testing whether a given number is prime is relatively easy.

Generating RSA keys can go wrong in a wide variety of ways. Prime numbers have to be chosen carefully, with specific mathematical properties, and they must never be reused.

Forming the message to encrypt with RSA is very subtle, and doing it improperly creates vulnerabilities. The most secure schemes for doing so are OEAP (for encryption) and PSS (for signatures). However, a known-insecure scheme called PKCS#1 v1.5 is still very widely used.

Checking whether a decrypted message has the expected padding is also very subtle. Implementing this operation without creating side channels is very difficult.