Appendix: Other Ciphers#

AES and ChaCha20 are the only ciphers that should be used in new applications, and this consensus is starting to be reflected in newer versions of standards like TLS 1.3.

However, there are other ciphers still in use in the world, and you may encounter some of them. This appendix contains details on two of the most important ones, and brief descriptions of a few others.

DES: Data Encryption Standard#

The Data Encryption Standard is a block cipher, developed in the late 1970s. It was the US government’s standard before AES[fip]. It should absolutely not be used in new applications, and it should be replaced in existing applications if possible.

DES has a block size of 64 bits and a key size of 56 bits. Both of these are considered much too small by modern standards; we’ll go into more detail on that in the Attacks section.

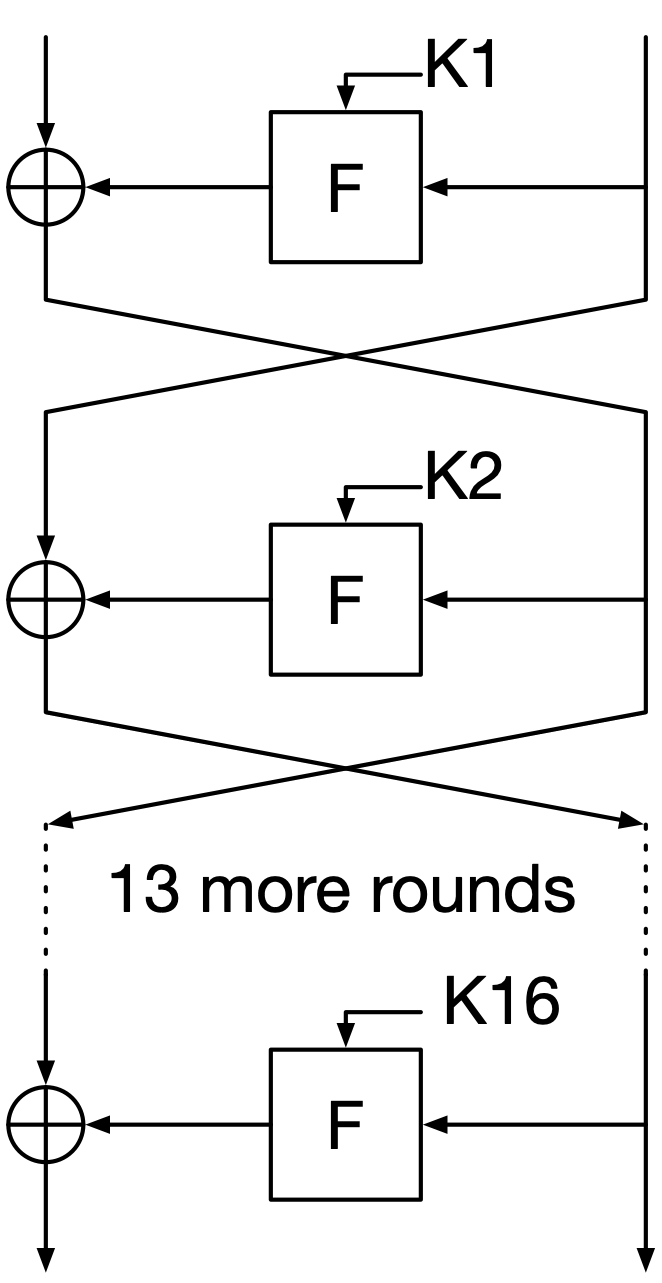

DES uses a common block cipher structure called a Feistel network. It is a round-based structure, and DES uses 16 rounds. Each round consists of the following steps (see Fig. 23):

The block is split into two equal halves (in DES’s case, 32 bits each).

The right half is fed into a round function, which combines the input with a subkey and does some other transformations, and outputs 32 bits.

The output of the round function is XORed with the left half of the block.

Except in the final round, the two halves are swapped.

The greatest advantage of the Feistel structure is that the logic of encryption and decryption are exactly the same; the difference is that the subkeys are used in the opposite order. This is especially important for hardware implementations: it means that there does not need to be separate physical circuitry for encryption and decryption, saving space and cost. Because DES was so thoroughly analyzed, the Feistel structure was too, and as a result, many other block ciphers use it (AES being a notable exception).

Fig. 23 DES’s Feistel structure.#

\(F\) is the round function, and \(K_1\) etc. are the subkeys. Each arrow represents 32 bits, except for the subkeys, which are each 48 bits. Note that the halves are not swapped after the last round.

Round Function#

DES’s round function has four steps. Recall that the input and output of the round function are both 32 bits.

Expansion: the 32-bit input is expanded to 48 bits by duplicating some of the bits and moving others around.

Key mixing: those 48 expanded bits are XORed with a 48-bit subkey.

Substitution: those 48 bits are split into eight groups of six bits each, and each six-bit group is used as input to a different S-box. Each S-box outputs four bits; therefore, the total output from all S-boxes is 32 bits.

Permutation: those 32 bits are reordered in a fixed but random-looking pattern.

You can see the operations providing non-linearity and diffusion, similar to how they do in AES.

Note that, unlike an AES round, the DES round function is not reversible: because each S-box maps a six-bit input to a four-bit output, there is no way to determine which input produced a given output. (There are 64 possible inputs, and only 16 possible outputs; therefore, there must be many different inputs that produce the same output.) However, thanks to the Feistel network structure, the round function doesn’t need to be reversible. To reverse each round of DES encryption, the round function just needs to output the same value it did during encryption, which the Feistel network achieves by using the subkeys in the opposite order during decryption.

Key Schedule#

DES’s key schedule is even simpler than AES’s. Recall that the algorithm requires one 48-bit subkey for each of 16 rounds.

Permute (reorder) the 56 bits of the main key, then split it into 28-bit halves.

Rotate each half left by 1 or 2 bits (depending on the round).

The next subkey is a permutation of 24 bits from the left half, and 24 bits from the right half. (The permutation is the same in every round.)

Repeat steps 2 and 3 until all required subkeys are generated.

This key schedule is now considered quite weak. In particular, there is no non-linearity in it: every bit of every subkey is just a bit from the main key. A main key that is all zeroes would result in every subkey being all zero. There is also poor diffusion: the left half of the key only affects half of the bits of each subkey (the same bits in each subkey, at that), and the same is true of the right half.

Triple DES (3DES)#

By the time DES’s small key size started to become concerning, there was no clear successor to DES. As a stopgap, Triple DES was developed: simply applying DES three times.

Triple DES uses a 168-bit key: three times 56. The key is split into three 56-bit parts, \(K_1\), \(K_2\) and \(K_3\). Then, Triple DES encryption consists of:

DES encryption with \(K_1\).

DES decryption with \(K_2\).

DES encryption with \(K_3\).

Triple DES encryption is the opposite: decrypt with \(K_3\), encrypt with \(K_2\), decrypt with \(K_1\).

There are three different keying options for Triple DES:

Option 1: \(K_1\), \(K_2\) and \(K_3\) are all different.

Option 2: \(K_1\) and \(K_3\) are the same, and \(K_2\) is different. This is effectively a 112-bit key, and was created as a compromise key length. There’s no particular reason to use it.

Option 3: all three keys are the same. This is effectively just single DES, since steps 1 and 2 cancel each other out. This option only exists to provide backward compatibility with DES: it’s a way to use an implementation of triple DES to do single DES. This is why step 2 is decryption instead of encryption.

Although Triple DES’s key size is not an issue, it was never thought to be a long-term DES successor. It shared DES’s 64-bit block size, which was also starting to become concerning. It had poor performance: it was three times as slow as DES. As time went on and more encryption was happening in software, DES’s poor performance in software was becoming a problem, and Triple DES only made it worse.

Finally, why is “double DES”, with a 112-bit key, not an option? The reason is that it is vulnerable to a meet-in-the-middle attack. Let’s imagine that double DES is encryption with \(K_1\) followed by encryption with \(K_2\), though the details don’t matter much to the attack.

The attack is a known-plaintext attack. It entails first single-encrypting the plaintext with all possible values of \(K_1\) (\(2^{56}\)), and storing the resulting ciphertexts. Then, try single-decrypting the ciphertext with all possible values of \(K_2\) (another \(2^{56}\)), and seeing if the result matches any of the stored ciphertexts from the first part of the attack. This means that the attack can be done with \(2^{56} + 2^{56} = 2^{57}\) single encryptions and decryptions overall, which is much worse than the \(2^{112}\) one would expect from a 112-bit key. The attack does require \(2^{56}\) blocks’ worth of storage, which is a lot, but within reach of a well-funded attacker.

Cryptanalysis#

DES has been extensively cryptanalyzed, and was the catalyst for the development of the two most important block cipher cryptanalysis techniques: differential cryptanalysis and linear cryptanalysis. We will not go into the details of either of these techniques, but only give an overview.

Differential cryptanalysis is a chosen plaintext attack. It was discovered in open academia by Eli Biham and Adi Shamir, and their application of it to DES was published in 1993[BS93]. The attacker chooses many pairs of plaintext with a constant difference — the difference between two plaintexts simply being their bitwise XOR. Then the attacker examines the XOR-difference between the corresponding ciphertexts, looking for patterns. If one ciphertext difference appears with a higher probability than others, the attacker can use that information to work backwards through the cipher and identify particularly likely values of subkeys.

Linear cryptanalysis is a known plaintext attack. It was discovered in open academia by Mitsuru Matsui, first published in 1992 and first applied to DES in 1993[Mat93]. The attacker looks for linear approximations that have a high or low probability of being true. A linear approximation is an equation of the form:

In words, the XOR of some plaintext bits and some ciphertext bits equaling zero. If a linear approximation is true for many (or few) known plaintext/ciphertext pairs, the attacker can use that information to work backwards through the cipher and identify particularly likely values of subkeys.

Note the similarity between these techniques. They both work by finding statistical patterns in the cipher’s output. They rely on probability, and they identify likely values of subkey bits. They can’t be treated as simple formulas that spit out a key when you plug in plaintext/ciphertext pairs. They also generally won’t recover all the subkey bits; rather, they narrow down the possible values of the subkeys to a point where, ideally, any unknown ones can be recovered by brute force. Recovering the actual key (i.e. the input to the key schedule) is not necessarily a goal; recovering all the subkeys is good enough.

Resistance to both of these techniques depends entirely on a cipher’s non-linearity; in the case of both AES and DES, that means their S-boxes. Since their discovery and publication, these two techniques have informed S-box design for all subsequent ciphers. Any new block cipher design must be resistant to both techniques in order to be taken seriously.

DES was specifically designed to be resistant to differential cryptanalysis — we’ll learn more about that in the History section below. Linear cryptanalysis is currently the best cryptanalytic attack on DES, requiring \(2^{43}\) known plaintexts (quite a lot) and around \(2^{39}\) steps (a lot, but certainly feasible). However, given how effective brute force is on DES at present, cryptanalytic attacks aren’t the biggest concern.

Performance#

When DES was originally designed, most encryption was done in hardware. As a tool exclusively for governments and militaries, it was natural to have purpose-built hardware to do it, and there was little need to do it in software.

This meant that DES was designed to be easy to implement in hardware —

specifically, to require a low number of transistors. This is why it relies

heavily on bit permutations, which require zero transistors: each wire carries

one bit, and you just connect the wires to different places. (By contrast,

something like AES’s MixColumns is much more complex to implement in

hardware.)

As computers became more widespread, and encryption became a tool that

individuals could use, software encryption became more common. In that context,

DES’s reliance on bit permutations had a significant detrimental effect on its

performance in software. Bit permutations are near-impossible to implement

efficiently in software, which generally is only good at dealing with whole

bytes at a time (like in AES’s ShiftRows).

It is interesting to see, in examples like this, the evolution of computing technology reflected in the evolution of cryptography. There are no modern block ciphers that use bit permutations, for exactly this reason.

RC4#

RC4 is a stream cipher, designed in 1987 by Ron Rivest1“RC” is variously said to stand for “Rivest Cipher” or “Ron’s Code”. Eagle-eyed readers may recall that there was an AES finalist named RC6; Rivest was one of its co-designers. RC6 isn’t similar to RC4, though.. It was secret until 1994, when RC4 source code was anonymously leaked to an Internet forum. It’s extremely simple — so simple you could memorize it. It was very widely used, possibly because its simplicity allows for very fast implementations. It was the encryption algorithm in WEP, the first security standard for wireless networking, and in the first versions of SSL.

RC4 is now considered insecure: it shouldn’t be used in new applications, and should be replaced in existing applications if possible. We’re only covering it here because it was, at one point, very popular; and because its design is rather different from other stream ciphers and CSPRNGs.

RC4 is based around a 256-byte state array, and two indexes into that array. We will call the array \(S\), and the two indexes \(i\) and \(j\). The state array is a permutation: throughout the operation of RC4, it contains each value from 0 to 255 inclusive exactly once. The only way it is modified during operation is to swap two of its entries.

The key can be of any length up to 256 bytes. (Note: bytes, not bits. 256 bytes is 2048 bits.)

First, the state array is initialized with the key as follows. Let \(K\) be the key as a byte array, and \(L\) be the length of the key in bytes.

For \(i\) from 0 to 255, set \(S[i] \leftarrow i\).

Set \(j \leftarrow 0\).

For \(i\) from 0 to 255, set \(j \leftarrow (j + S[i] + K[j \Mod L]) \Mod 256\), then swap \(S[i]\) and \(S[j]\).

Once the initialization is done, pseudorandom bytes are generated as follows:

Set \(i \leftarrow 0\) and \(j \leftarrow 0\).

To generate a byte:

Set \(i \leftarrow i + 1 \Mod 256\).

Set \(j \leftarrow j + S[i] \Mod 256\).

Swap \(S[i]\) and \(S[j]\).

The output byte is \(S[(S[i] + S[j]) \Mod 256]\).

The byte generation is very structurally similar to the initialization: the only difference is that the initialization adds in a key byte in the step that computes \(j\). This contributes to the ease of RC4 implementation, especially in hardware; the two operations can share circuitry.

Notice two things about RC4 that contrast with other stream ciphers we’ve seem, like ChaCha20 and CTR mode:

RC4 has no nonce. This means that you must not reuse a key, since that is the only thing that ensures the uniqueness of the keystream. In practice, since RC4 has variable key length, applications will include a nonce (like a message counter) within the RC4 key.

The internal state continuously evolves over the course of keystream generation, which means that RC4 is not random-access — you cannot compute the \(n\)th bit of keystream without computing all the bits before it. By contrast, the state of ChaCha20 resets to a known value with every 512 bits of keystream, so it is random-access to within 512 bits. CTR mode offers random access to within the block cipher’s block size.

Security#

There are many attacks against RC4, some of them practical.

One important problem is that there are statistical correlations between the first few bytes of the keystream, and some of the bytes of the key, thus leaking information about the key. Any practical usage of RC4 should discard at least the first 256 bytes of the keystream before using any to encrypt. This introduces an extra complication into protocols using RC4: the participants must agree on how much of the keystream to discard.

One particularly effective exploitation of this problem was found in 2001 by Scott Fluhrer, Itsik Mantin, and Adi Shamir to practically break RC4 as used in WEP, the wireless-networking security standard[FMS01]. The RC4 keys that WEP uses are a concatenation of a long-lived secret (the password to the WiFi network) and a nonce, where the nonce is known to the attacker. Under those conditions, this attack can recover the long-lived secret from a few million WiFi packets, which, on a busy network, would probably take less than an hour to collect. Since this is a related-key attack, it can be mitigated by not using related keys: for example, hash the long-lived secret plus nonce before using it as an RC4 key. (Also, don’t use WEP anymore.)

A notable property of the state updates in the byte generation algorithm is that they are reversible. Given \(S\), \(i\), and \(j\), you can easily compute what the state was before the last byte was generated, and so on all the way back to the first byte of the keystream. (Note that it is not easy to do this given only the keystream; you need the full internal state.) This is not ideal for security; ideally, a stream cipher should be robust against state compromise. Furthermore, in 2008, Eli Biham and Yaniv Carmeli found a way to recover the key from the internal state array[BC08]. If, as in WEP, the key includes a long-lived secret, this attack can likely recover it given a state compromise.

There are many other attacks, but the one that seems to have put the final nail in RC4’s coffin is called NOMORE, discovered in 2015 by Mathy Vanhoef and Frank Piessens[VP15]. It is a practical attack against RC4 as used in TLS: if an attacker can induce a victim to encrypt a partially-known plaintext many times, the attacker can recover the rest of the plaintext. This can be used, for instance, to compromise web cookies, allowing the attacker to log into websites as the victim. As a result, modern browsers no longer allow the use of RC4 in TLS.

Camellia#

Camellia is a block cipher, published in 2000 by a joint team from Mitsubishi Electric2One of the Mitsubishi team members was Mitsuru Matsui, the inventor of linear cryptanalysis. and NTT[AIK+00]. Even though it’s over 20 years old, it’s one of the youngest block ciphers around; development of new block ciphers essentially stopped with the standardization of AES in 2001.

Camellia is from the modern generation of block ciphers that has a 128-bit block size, and it takes the same range of key sizes as AES: 128, 192, or 256 bits. In general, it has similar characteristics to the AES finalists, although it was not submitted to the AES competition.

Camellia is supported in TLS 1.2 (although not in TLS 1.3), and is implemented in OpenSSL and GPG. There are no security concerns with using it — no cryptanalysis has gotten close to a concerning break — but there’s just no particular reason to use it. Use AES instead.

Blowfish#

Blowfish is a block cipher, published in 1994 by Bruce Schneier[Sch94]. It enjoyed significant popularity in the years just before AES was introduced. It offered better security than DES, better performance than Triple DES, and was not patented (as many published ciphers at the time were).

An interesting aspect of Blowfish is that it allows for a variable-length key, of any length up to 448 bits. We know now that a key that long is overkill; 256 bits is plenty. Blowfish was somewhat infamous for its complex, time-consuming key schedule; in fact, the time-consuming nature of this key schedule is what led the designers of bcrypt to adapt it for their algorithm.

Another distinctive feature of Blowfish is that it uses key-dependent S-boxes (unlike, for example, AES’ fixed S-box). This feature, along with the complex key schedule, was inherited by Twofish, one of the five AES finalists. (Bruce Schneier, the designer of Blowfish was on the team that designed Twofish.)

It has a block size of 64 bits, which, as we’ve seen, is too small for modern times. There was never any concerning cryptanalysis against it, but there’s no reason to use it anymore.