Block Cipher Modes#

As we saw in the previous chapter, block ciphers only operate on pieces of data that are exactly their block size. Block cipher modes are answers to the question: what if we have more than one block’s worth of data?

There are many block cipher modes, and we’re only going to cover the most widely-used ones in detail.

Some modes are unauthenticated modes, providing only confidentiality. Others are authenticated modes; they compute a MAC simultaneously with encryption, and thus provide integrity and authentication as well.

Unauthenticated Modes#

ECB: Electronic Codebook#

The most obvious answer to the question “what if we have more than one block’s worth of data?” is to simply chop the plaintext into block-sized pieces (padding the last piece if necessary), separately encrypt each piece with the block cipher, then concatenate all the ciphertexts together. This is called Electronic Codebook, or ECB mode.

We can express this in the form of equations; we’ll do this for each mode we look at. \(P_1, P_2\), etc. are the plaintext blocks, and \(C_1, C_2\), etc. are the ciphertext blocks. \(E_K\) represents the block cipher’s encryption function with key \(K\), and \(D_K\) represents decryption. The equation for encryption is on the left, and for decryption on the right.

This is very important: do not use ECB mode! It is extremely insecure.

In ECB mode, the ciphertext for each block depends only on the plaintext of that block. Patterns in the plaintext that are larger than blocks come through exactly as-is in the ciphertext. Though the underlying block cipher may provide good diffusion within blocks, ECB provides zero diffusion across blocks.

As an example, I divided the text of the previous chapter into 128-bit blocks, and searched for any that were the same. There were several (underscores represent the space character):

_subkey with the_block, byte-by-ipher cryptanalypproximation is_fferential cryptmplementations,_

These aren’t just repeated phrases, but repeated phrases that lined up on 128-bit boundaries the same way. If that text were to be encrypted with ECB mode, all instances of these repeated plaintext blocks would encrypt to the same ciphertext block, and this pattern would be easy to find in the ciphertext with a few lines of code.

Most plaintext contains this kind of pattern, and making it obvious to a ciphertext-only attacker that multiple blocks of plaintext are identical is an unacceptable level of confidentiality failure.

Caution

We’re only covering ECB mode because it’s an obvious yet egregiously wrong answer to the motivating question at the beginning of the chapter. There’s never any reason to use ECB.

CBC: Cipher Block Chaining#

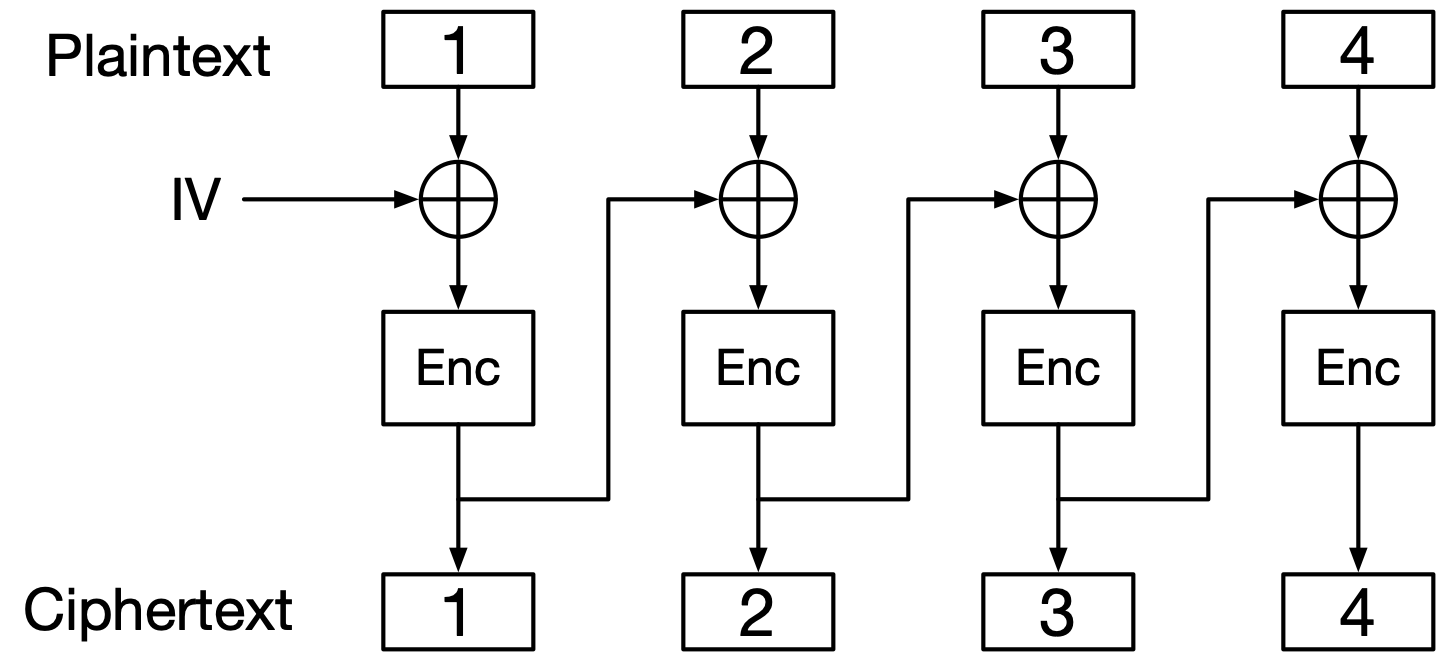

In CBC mode, the plaintext is padded and chopped into block-sized pieces, and then each plaintext block is XORed with the preceding ciphertext block before being encrypted with the block cipher. The first plaintext block, which has no preceding ciphertext block, is XORed with a block-sized chunk of data called an initialization vector, almost always abbreviated to IV.

IVs are another type of “neither plaintext, nor ciphertext, nor key” cryptographic data. In CBC mode, the IV must be unpredictable in order to be secure. In practice, they are usually generated randomly for each plaintext.

Unlike stream cipher nonces, CBC-mode IVs are not absolutely required to be unique, but making them unpredictable by generating them randomly also makes them unique with high probability. CBC-mode IVs do not need to be kept secret; indeed, they’re usually transmitted or stored as-is alongside the ciphertext.

See Fig. 9 for a diagram of encryption, and Fig. 10 for a diagram of decryption. Here is CBC in equation form, encryption on the left and decryption on the right:

Fig. 9 CBC encryption.#

Enc represents the block cipher’s encryption function.

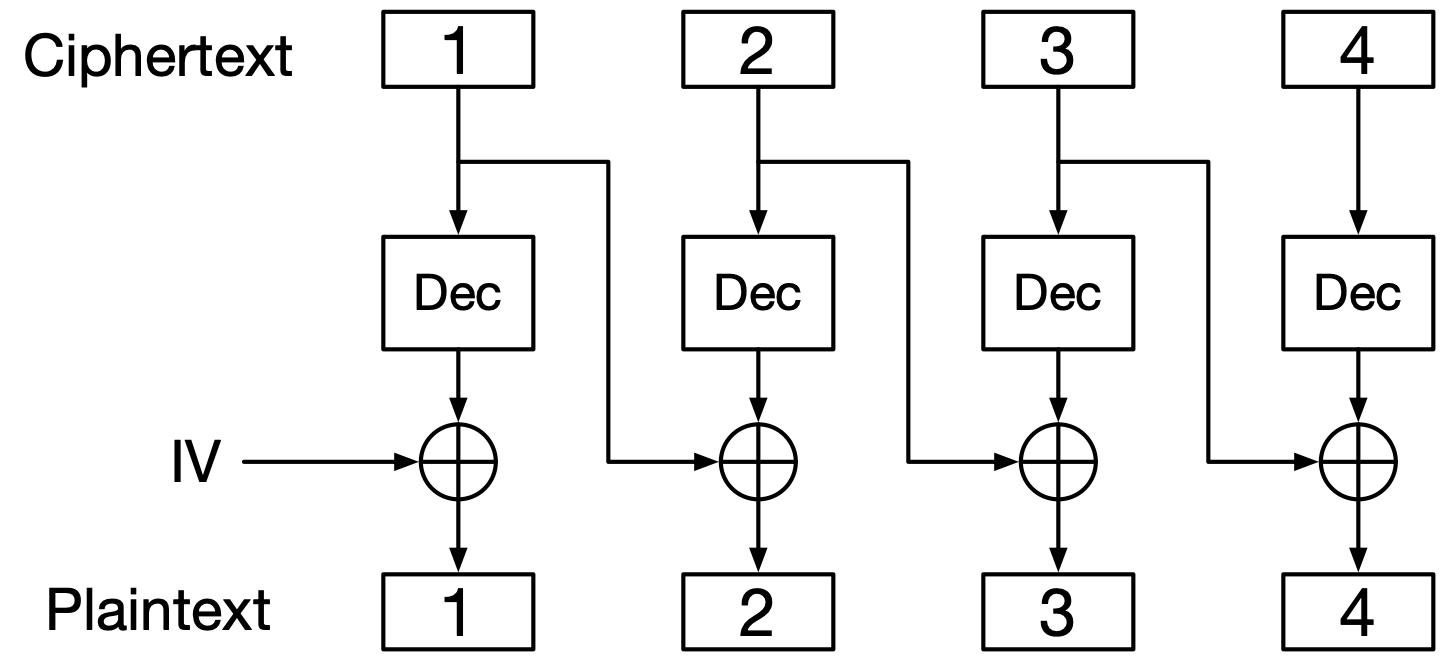

Fig. 10 CBC decryption.#

Dec represents the block cipher’s decryption function.

This way, each block of ciphertext depends on the corresponding block of plaintext and all previous ones too. Thus, identical blocks of plaintext are virtually certain to result in different blocks of ciphertext.

There are several noteworthy properties of this arrangement:

CBC encryption is not parallelizable. This means that you can’t encrypt multiple blocks at the same time, because encrypting one block requires the ciphertext of the previous block.

By contrast, decryption is parallelizable. To get plaintext block number \(n\), all you need is ciphertext blocks \(n-1\) and \(n\), and you have those from the start. Implementations that are capable of doing multiple decryption operations at the same time can speed up CBC decryption this way.

The fact that decryption is parallelizable means that it is random-access. If you want to decrypt only a single block in the middle of the ciphertext, you can. Encryption, however, is not random-access.

If you decrypt with the wrong IV, the first plaintext block will be incorrect, but all the others will be correct. Some CBC implementations take advantage of this property: they prepend a random block to the plaintext before encrypting, and do not transmit or store the IV. Decryption uses any IV, then discards the first block of the decrypted plaintext.

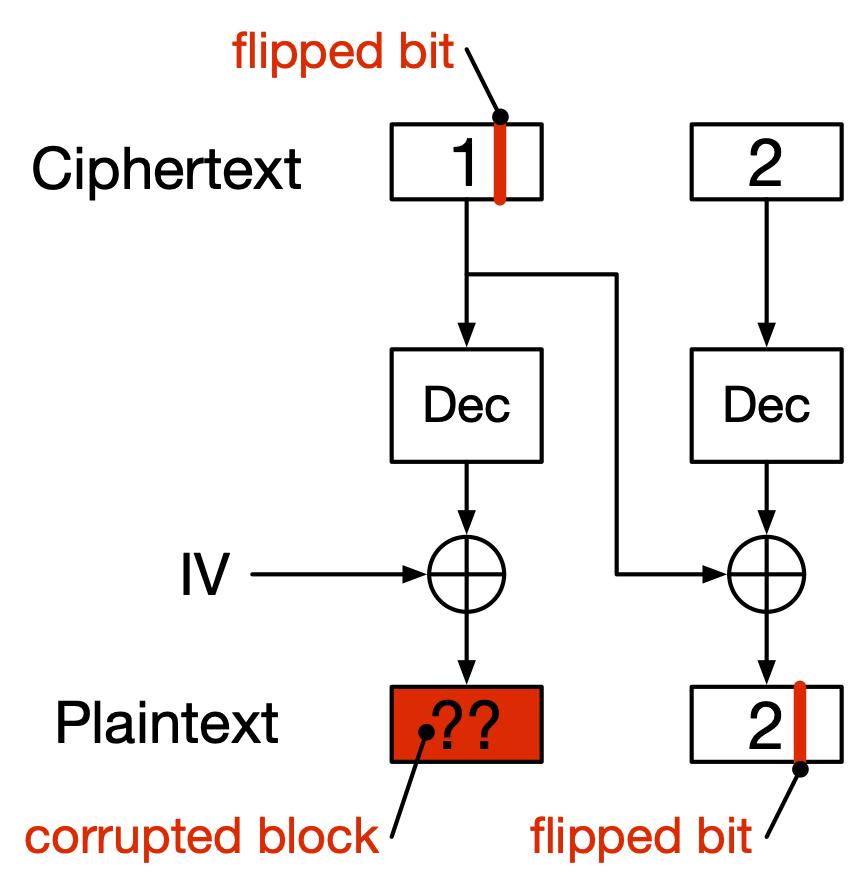

Another noteworthy property of CBC is that it is malleable; recall the definition of malleability we saw in a previous chapter. CBC isn’t quite as malleable as a stream cipher, though. Specifically, if an attacker flips a bit in ciphertext block number \(n\), then two things will happen (see Fig. 11):

The corresponding bit of plaintext block number \(n+1\) will be flipped.

Plaintext block \(n\) will be corrupted; i.e. it will be random-looking garbage.

Fig. 11 Consequences of flipping a single ciphertext bit in CBC.#

CBC’s malleability has given rise to a very well-known attack called a padding oracle attack, originally published by Serge Vaudenay in 2002[Vau02]. It requires access to a padding oracle: a system that an attacker can send ciphertext to, and learn whether the decrypted plaintext has valid padding or not. In practice, such a system does not explicitly or intentionally say whether the plaintext has valid padding. Instead, the attacker infers the padding validity via a side channel: either a timing difference or a differential fault. Invalid padding may result in a particular error message, or a consistently faster or slower response from the system than for other types of errors.

In any case, knowing whether a plaintext’s padding is valid or invalid exposes information about the plaintext. It’s only a little information at a time, but that’s enough for an attacker. The padding oracle attack can decrypt a block of plaintext with, on average, only a couple thousand calls to the padding oracle, making it very much a practical attack. When it was first published, a huge variety of server software was found to be vulnerable to it, including many implementations of TLS, which we’ll see in a later chapter. Despite having been published in 2002, variants of the attack were found to work as late as 2013[AP13].

The padding oracle attack is not applicable to stream ciphers, despite their malleability, because their plaintexts are not padded.

CBC-MAC#

There are several ways of creating a MAC algorithm that uses a block cipher under the hood. The one that has probably seen the most use is CBC-MAC. Its basic definition is very simple: encrypt the message in CBC mode, using an IV of all zero bits, then take the last block of the ciphertext as the tag.

CBC-MAC requires some care to use securely. If any message can be a prefix of another, CBC-MAC is insecure, allowing attackers to forge tags. One solution is to prepend the length of the message to the actual message, but this is problematic for applications where the length of the message may not be known when the MAC computation starts.

CBC-MAC also fails catastrophically if the same key is used for CBC-mode encryption and CBC-MAC of a message (if the tag is computed on the plaintext). If that happens, an attacker can replace the entire ciphertext, except for the final block, with whatever they want, and the resulting tag will be the same.

Other block cipher-based MACs are the confusingly named CMAC and OMAC. You generally shouldn’t use any of these constructions. They aren’t necessarily insecure (though they are tricky to use securely), but they are really only useful for situations where you have an implementation of a block cipher available, but not of a MAC algorithm. In the modern world, this basically never happens. Either use an AEAD scheme, or use HMAC (described in a later chapter).

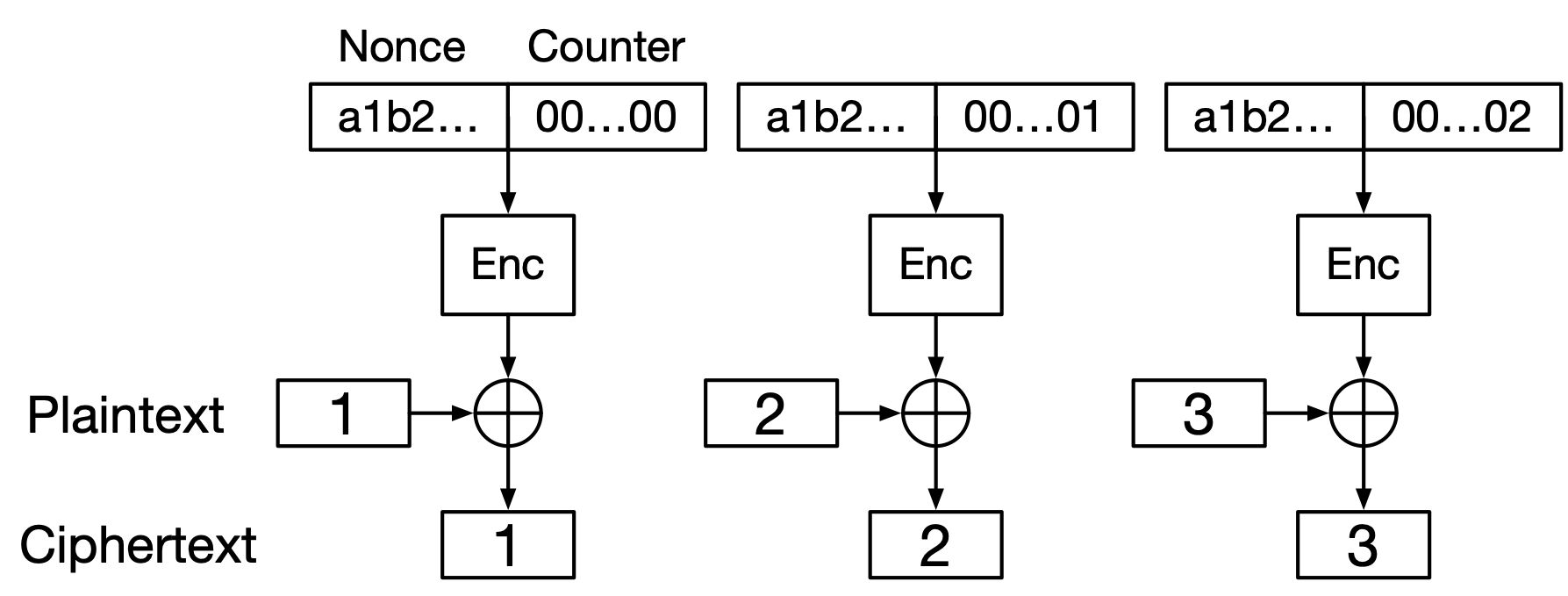

CTR: Counter Mode#

CTR mode essentially converts a block cipher into a stream cipher. Neither plaintext nor ciphertext ever goes into the block cipher. Instead, you construct synthetic blocks that include an integer counter and encrypt those. The output is then used as a keystream: you XOR it with the plaintext to produce ciphertext, and vice versa.

The blocks that get encrypted to produce the keystream consist of two equal-sized parts: first a nonce, then an integer counter. The integer counter starts at zero, and is incremented with every block of keystream produced, much like ChaCha20’s block counter. The nonce stays the same throughout all the blocks of keystream produced for the encryption of a single plaintext (or decryption of a single ciphertext).

The nonce for CTR mode has the same properties as the ChaCha20 nonce: it must be unique per-key, and it is a catastrophic security failure if a nonce is reused with the same key — the cipher degrades into being the repeating-key XOR cipher. However, it does not need to be unpredictable or secret.

See Fig. 12 for a diagram. The equations are as follows. The symbol \(||\) denotes concatenation, and the nonce is the same value for every block. Note that decryption still uses the block cipher’s encryption function; its decryption function is never used.

Fig. 12 CTR encryption.#

Decryption is exactly the same, except with the plaintext and ciphertext swapped.

Advantages of CTR mode:

No padding is required, which means that you don’t have to choose or implement a padding scheme, and also that padding oracle attacks are not possible (even though CTR mode is malleable).

It only uses the block cipher in encryption mode; i.e. decryption mode does not even need to be implemented.

Encryption and decryption are fully parallelizable. CTR mode offers random access.

Disadvantages:

CTR ciphertext is malleable, to a higher degree than CBC mode. Recall that flipping a bit in CBC ciphertext flips a bit in the next block of plaintext, but completely corrupts the current block of plaintext. In CTR mode, flipping a bit of ciphertext flips the corresponding bit of plaintext and nothing else.

If a nonce is reused with a key, CTR’s security completely breaks down. Whereas CBC mode with a reused IV preserves some confidentiality, CTR with a reused nonce is just the XOR cipher.

A few cryptography researchers have been wary of CTR mode, because it involves exposing the block cipher to inputs with a very strong pattern. The idea is that if the block cipher does a poor job of hiding patterns in its input, CTR mode will exacerbate the problem. In practice, this is not a concern.

Other Modes#

CBC and CTR are the most commonly-used unauthenticated modes, but there are several others. We won’t go into detail about them here, but only provide their equations. They are not commonly used in practice.

Cipher feedback mode, or CFB:

\begin{align*} C_0 & \leftarrow IV & C_0 & \leftarrow IV \\ C_i & \leftarrow P_i \oplus E_K(C_{i-1}) & P_i & \leftarrow C_i \oplus E_K(C_{i-1}) \end{align*}Output feedback mode, or OFB:

\begin{align*} S_0 & \leftarrow IV & S_0 & \leftarrow IV \\ S_i & \leftarrow E_K(S_{i-1}) & S_i & \leftarrow E_K(S_{i-1}) \\ C_i & \leftarrow P_i \oplus S_i & P_i & \leftarrow C_i \oplus S_i \end{align*}

Authenticated Modes#

The above modes only provide confidentiality, and we’ve seen in the chapter on authenticated encryption that that isn’t secure. Without integrity and authentication, attackers can tamper with ciphertext undetected; this allows for attacks like the CBC padding oracle attack to succeed.

Authenticated modes combine an unauthenticated mode with an additional computation that produces a tag, much like ChaCha20-Poly1305. Most authenticated modes are AEAD schemes, optionally allowing the authentication of additional data (the AAD) that does not get encrypted. Just like ChaCha20-Poly1305, authenticated modes define two operations: sealing (encrypting and producing a tag) and opening (verifying a tag and decrypting).

In practice, you should use an AEAD mode if you have a choice of modes. In the next chapter, we will see another way of adding integrity and authentication to a confidentiality-only cipher mode, but AEAD is now the favored approach.

GCM: Galois/Counter Mode#

GCM is an AEAD mode[MV]. It is simply CTR mode for encryption, along with

an additional calculation involving a Galois-field multiplication (like AES’ MixColumns step, and described in the appendix) to produce a tag.

GCM is only defined for ciphers with a block size of 128 bits. It uses a single key, for encryption and authentication. After doing CTR-mode encryption, it computes the authentication tag as follows:

Compute the hash key, which we will call \(H\), by using the block cipher to encrypt a block of all zero bits.

Pad the AAD, if any, with zero bits1Note that this padding is not reversible. It doesn’t need to be, because this is only an input to the authentication tag. The original AAD and ciphertext will not be (indeed, cannot be) restored from the tag. so that its length is a multiple of 128 bits. Do the same with the ciphertext.

Initialize the tag as 128 zero bits.

For each block of the AAD, and then each block of the ciphertext, do the following: XOR it with the current tag, then Galois-multiply that by \(H\), and set the current tag to that result.

After all the AAD and ciphertext is processed, create a final block consisting of the bit length of the AAD (pre-padding), followed by the bit length of the ciphertext (pre-padding), both as 64-bit big-endian integers. XOR this with the current tag, Galois-multiply that by \(H\), and set the current tag to that result.

XOR the current tag with \(H\). The result is the final authentication tag.

Verifying a GCM tag entails simply doing the same computation on the ciphertext and comparing the result against the purported tag. The computation as defined above is not parallelizable, but there is an alternative way to compute it that is parallelizable.

Notice that GCM follows the proper order of operations: it computes the tag on the ciphertext, rather than the plaintext.

Modern Intel CPUs have hardware support for Galois-field multiplication. Combined with their hardware support for AES, this allows for highly efficient implementations of AES-GCM.

Since GCM’s encryption part is the same as CTR mode, it is just as crucial not to reuse a nonce with a key. However, with GCM, the danger is even more serious: a nonce that is repeated just a few times can directly reveal \(H\), the hash key for the authentication part[Jou]. This is disastrous, allowing an attacker to forge an authentication tag for any ciphertext2This is possible because the final step of GCM is to XOR the accumulated tag with \(H\). One response to the initial publication of GCM is that, instead, that step should be to encrypt the accumulated tag with the block cipher, which would have avoided this vulnerability. But, for whatever reason, we’re stuck with the XOR step.. Any system that uses GCM must have an airtight way of creating unique nonces.

In February 2022 — very recently! — researchers discovered that Samsung got this wrong in TrustZone, the secure-execution feature of their smartphones[SRW22]. The researchers were able to use a repeated nonce to extract secret data from a part of the hardware that was not supposed to let that data out.

Synthetic Initialization Vectors#

Because nonce reuse in CTR and GCM has such dire consequences, there is demand for a mode that preserves the advantages of those modes (no padding; speed) that is more robust against misuse.

Synthetic initialization vectors are one way to build such a mode. The simplest is called AES-GCM-SIV[GLL19]. It requires a key and nonce as input, and then it runs a computation (using Galois-field multiplication) on the key, nonce, and plaintext to create the authentication tag. Then that authentication tag is used as the nonce for AES-CTR encryption of the plaintext.

Despite the name, this is not just “GCM with a computed nonce”; the computation of the authentication tag is different.

If a nonce is reused with AES-GCM-SIV, an attacker gains no information, and they cannot even tell that the nonce was reused (unless the same message is encrypted twice with the same nonce.) However, even if you use AES-GCM-SIV, you should not stop caring about nonce uniqueness; you should still make an effort to use unique nonces. AES-GCM-SIV is not a panacea; it’s better to think of it as a stopgap for the (in practice somewhat rare) situations when it is genuinely hard to produce unique nonces.

There are some performance-related downsides of AES-GCM-SIV. First, you have to compute the authentication tag before encryption can start. Second, on the decryption end, you have to decrypt the ciphertext before you can verify the authentication tag, since the authentication tag is computed on the plaintext, instead of the ciphertext. Neither of these is true of GCM itself.

AES-GCM-SIV is a reasonable choice for authenticated encryption if you can’t guarantee unique nonces for GCM. If producing unique nonces is not a problem, then plain AES-GCM is a better choice.

Other Modes#

Another AEAD mode is CCM mode, which stands for “Counter with CBC-MAC”. It is less commonly used than GCM because of inferior performance. It uses CTR mode for the encryption part, and then CBC-MAC for the authentication part.

There are several other AEAD modes (OCB, EAX, CWC), but they are not in common use, so we won’t go into them.

Full Disk Encryption#

You may wonder why random access is a desirable feature of a block cipher mode. Until now, we’ve been implicitly thinking only of encrypting messages: discrete chunks of data that are transmitted back and forth across some insecure medium like a network, or stored individually in a file. In those contexts, random access isn’t something that’s obviously needed.

Another major application for encryption, however, is full disk encryption (FDE). This is when the contents of an entire storage device (usually a hard disk or solid state drive) are encrypted, rather than single files or parts of files. FDE is managed by the operating system, and is mostly transparent to users. The brand name for Windows’ FDE feature is BitLocker, and for macOS it is FileVault.

FDE has some interesting constraints to work with, some of which we haven’t seen before:

Any part of the disk can be read or written at any time.

It must not incur a significant performance penalty: reads and writes to the disk must be almost as fast as reads and writes to a non-encrypted disk.

It must not incur a significant space penalty: any additional data required by the FDE scheme must be small, and ideally nonexistent.

Attackers are assumed to have the following capabilities:

They can read and modify the raw contents of the disk (i e. the ciphertext) at any time.

They can write plaintext files (and then see the effects of doing so on the disk contents).

They can write data to unused parts of the disk and request decryption of it.

Most notably, these properties mean that authenticated encryption is not an option. Computing a single authentication tag for the entire disk would make writes prohibitively slow. Computing tags for smaller parts of the disk individually would reduce the performance problem, but would incur a space penalty. It turns out that there is no acceptable tradeoff here: any granularity of authentication that allows acceptable write performance incurs too high a space penalty.

The same issue precludes the use of CBC mode, which requires the storage of IVs. Recall that in CBC encryption, each ciphertext block depends on every ciphertext block in the chain before it. If FDE used CBC mode, writing to a block early in a chain would require re-encrypting every block after it in the chain. That would be prohibitively slow unless the disk were split into a large number of short chains, which would incur too much of a space penalty to store all the IVs.

Given that authenticated encryption is off the table, any malleable mode is also off the table. Malleability would allow attackers to make precise modifications to the plaintext, especially since it is likely (by the nature of filesystems) that attackers would know which ciphertext bits on the disk correspond to particular plaintext files.

Beyond that, there is another reason to reject the use of CTR and similar modes that involve XORing a keystream with plaintext. Recall that such modes fail catastrophically if a keystream, or part of one, is reused. Modifying any part of a CTR-encrypted disk would entail reusing part of a keystream (since a specific part of the disk must be encrypted/decrypted the same way every time) and thus is insecure, and not an option.

Such problems could be avoided by using different keys for different parts of the disk (with the keys somehow derived from the disk location where they are used), but that would incur an unacceptable performance penalty. Recall that, before using a key to encrypt or decrypt, a block cipher must run its key schedule on the key; this takes too much time to be acceptable for an FDE scheme to do often.

By now, you may be thinking that FDE seems like a very difficult problem. It is! There really is not anything like a good solution for it. In fact, it’s best to think of FDE as a last resort of security. Truly critical data should be encrypted and authenticated at a higher level: the filesystem level, or the user level.

Tweakable Encryption Modes#

FDE requires a different kind of mode, from a class of modes called tweakable encryption. A tweakable mode takes three inputs: the usual plaintext/ciphertext and key, plus a tweak, a small chunk of data[LRW02]. Different tweaks make the block cipher behave differently, even with the same key.

In the FDE context, the disk is notionally divided into sectors3The term “sector” comes from hard disk drives, which are logically divided into ring-shaped tracks and pie-slice-shaped sectors. In this context, we use “sector” regardless of the underlying storage medium., which are usually around 512 bytes, and the number of the sector is used as the tweak.

Because these modes are very specialized in purpose — there is no reason to use them other than for FDE — we won’t go into great detail on them. We’ll only

One very simple tweakable mode is called XEX mode, for “XOR-encrypt-XOR”. For each block of plaintext, it computes a block-sized value \(X\) from the tweak. Then it XORs \(X\) with the plaintext, encrypts the result, and XORs the result with \(X\) again to produce the ciphertext. \(X\) is derived from the sector number by a Galois-field multiplication, and is different for every block.

XEX by itself has nothing to say about sectors that are not evenly divisible by the cipher’s block size. The solution is XTS mode: XEX with ciphertext stealing. XTS is used by macOS’s FileVault[CGM12].

Ciphertext stealing is an alternative to padding that is useful in the FDE context because it results in a ciphertext that is exactly the same size as the plaintext. It involves filling the remaining space in the last plaintext block with the end of the second-to-last ciphertext block. That “stolen” part of the second-to-last ciphertext block is then discarded in the final ciphertext[Sch96a].

Outside the FDE context, padding (or a no-padding mode) is almost always used instead of ciphertext stealing because it is simpler, and the slightly increased size of the ciphertext is more tolerable.

Stream vs. Block#

After all this, there’s a natural question: why would one use a stream cipher instead of a block cipher, or vice versa?

Before getting into that, it’s important to specify that we’re talking about a stream cipher versus a block cipher in a mode that doesn’t turn it into a stream cipher. So, for our purposes here, let’s talk about CBC mode in particular.

The names suggest one possible reason: a stream cipher is a natural fit for data that is in the form of a stream, such as coming in or going out over a network. Data being sent out over a network doesn’t necessarily come in block-sized chunks. Consider an application like a VPN, which must deal with whatever network traffic it’s asked to send. If it’s using a block cipher in CBC mode, and it’s asked to send an odd-sized amount of data, it must pad the final block before sending it out; this results in sending extra bytes over the network. In the worst case, imagine that it’s asked to send one byte, then one byte, then one byte, and so on. It would end up sending 15 bytes of padding for every byte of actual data. By contrast, a stream cipher can generate exactly as much keystream as is needed.

Stream ciphers are often well-suited for constrained computing environments like smart cards: they generally have low memory requirements and are very simple to implement. You’ve seen this already: ChaCha20 is considerably simpler than AES. ChaCha20 is so simple that people memorize it; people don’t memorize AES. (It has a 256-byte S-box, for one thing.)

On the other hand, one consideration in favor of AES in particular is that there is currently no stream cipher that has the kind of institutional blessing that AES does. AES has been the target of rigorous cryptanalysis for many years, and might be the most-analyzed cipher of the computer age (possibly second to DES). Much like the old saying, “no one ever got fired for buying IBM”, no one ever got fired for choosing AES as a cipher.

In addition, stream ciphers are not suitable in situations where there is not an ironclad way to ensure nonce uniqueness. Full-disk encryption, which we saw previously, is an example; it’s impossible to use stream ciphers for FDE.

Key Takeaways#

A block cipher mode is a way of using a block cipher to encrypt messages that are larger than the cipher’s block size.

Never use ECB mode.

CBC mode is a reasonable choice for unauthenticated encryption. It uses an initialization vector that should be unique for each message, but is not secret.

CTR mode is a reasonable choice for unauthenticated encryption. It does not require padding. It uses a nonce that must be unique for each message, but is not secret. Reusing a nonce with a key is catastrophic.

Don’t use CBC or CTR mode by themselves; always combine them with something that provides integrity and authentication.

Galois/Counter mode is a reasonable choice for authenticated encryption. It combines CTR encryption with an additional computation to provide authentication and integrity. Like CTR mode, it requires a unique non-secret nonce, and it’s catastrophic to reuse a nonce with a key.

Full disk encryption uses specialized modes for that purpose only, because of its unique requirements.