Bits, Bytes, and Words#

The math that’s used in cryptographic algorithms is made of fairly simple building blocks. We’ll cover enough of it that you’ll be able to fully understand the definition of every algorithm we cover.

There are two mostly-unrelated areas of math used in cryptographic algorithms. One is used mostly in symmetric-key algorithms and hash functions, and the other is used mostly in asymmetric-key algorithms. This chapter covers the former; a later chapter covers the latter.

The math that’s used to analyze cryptographic algorithms is considerably more advanced, and we won’t be covering it in this course.

Fundamentals#

Before we get into any detail, let’s quickly cover the actual things we’re doing math on.

The normal way we write numbers is called base-10 notation, or decimal notation. This means that we have ten different digits we can use (0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9). We can put them together to represent larger numbers; for example, we represent three hundred and forty-six by putting a 3, a 4, and a 6 next to each other: 346. The “3” represents three times a hundred, the “4” represents four times ten, and the “6” represents six times one. Those multipliers (a hundred, ten, and one) are successive powers of the base (\(10^2\), \(10^1\), and \(10^0\) respectively).

We can write numbers in other bases by using a different set of digits. We can write numbers in base-2 or binary notation by only using the digits 0 and 1. For example, 346 in base-2 notation is 101011010. To break this down:

Adding up the numbers on the bottom row, we get \(256 + 64 + 16 + 8 + 2 = 346\).

Base 2 is important because all information in computers is represented as bits. A bit is a value that is either 0 or 1. If we want to represent anything else in a computer — numbers, text, images, sound — we need some way to translate it into a sequence of bits. For integers, base 2 is how it’s done1There are ways to represent non-integers too — numbers with fractional parts like 3.14 — but those are beyond the scope of this course.. We’ll cover text later; images and sound are beyond the scope of this course.

You can write an integer of any size in base 2, just as you can in base 10. However, computers deal with fixed-size sequences of bits. A sequence of eight bits is called a byte. The size of a sequence of bits is often called the width; e.g. a byte is eight bits wide.

A sequence of 32 bits is often called a word. Sometimes, though, “word” can refer to a bit sequence of another size, such as 64 bits. In this course, we’ll use “word” to mean 32 bits by default, and specify explicitly when we mean something else.

Within a sequence of bits representing an integer, we’ll refer to the bit corresponding to the biggest multiplier as the most-significant bit or MSB, and to the bit corresponding to the smallest multiplier as the least-significant bit or LSB. We always write the MSB at the left, and the LSB at the right.

Hexadecimal Notation#

In cryptography, you’ll also very commonly see numbers and bytes written in base-16 notation, or hexadecimal (“hex” for short).

To write numbers in hex, we need 16 digits. In addition to the ten decimal

digits, hex notation uses the letters A through F (case doesn’t matter). The

letter a represents ten, b represents eleven, and so on through f, which

represents fifteen.

For example, 491 would be written in hex as 1EB:

Adding up the numbers at the bottom, we get \(256 + 224 + 11 = 491\).

In this course, and in the world in general, you will usually see hex values

prefixed with the characters 0x. Most programming languages support writing

numeric literals in hex as long as you prefix them with those characters, and

the convention has spread to written materials in general. It also helps to

distinguish hex numbers from decimal numbers when the digits a through f

aren’t present. E.g. 12 is twelve, but 0x12 is eighteen.

Hex notation is very useful in computing contexts because one hex digit

corresponds exactly with four bits. With two hex digits, therefore, you can

represent exactly the same set of values that you can represent with one byte.

This is such a useful convention that you will often see byte values less than

sixteen written with a leading zero — e.g. 0x0C rather than just 0xC.

Endianness#

Computer memory fundamentally works in terms of bytes: you can think of a

computer’s memory as simply a huge array of bytes. When a computer stores a

sequence of more than 8 bits into memory, like a 32-bit integer, it must break

the sequence down into bytes and put them in memory in a certain order. There

are two conventions by which it can do so: big-endian and little-endian.

Let’s look at examples of storing the 32-bit integer 0x12ABCDEF.

In the big-endian convention, the integer is chopped into four bytes and stored

into four adjacent bytes of the computer’s memory. The most-significant byte is

stored in the leftmost of those four adjacent bytes (i.e. at the lowest index

in memory), and the least-significant byte is stored rightmost. The bytes of

our example integer would thus be stored in memory in the following order:

0x12, 0xAB, 0xCD, 0xEF.

In the little-endian convention, the order is swapped: the least-significant

byte is stored leftmost, and the most-significant byte is stored rightmost.

The bytes of our example integer would be stored in the following order: 0xEF,

0xCD, 0xAB, 0x12.

Any time there is a conversion between larger-than-a-byte numbers and byte sequences, endianness must be specified. This is an important part of some cryptographic algorithms: they will take byte sequences as input, split them up into four-byte chunks, and interpret each chunk as a 32-bit integer to do math on.

Both conventions are used in many contexts, and both have upsides and downsides. Intel and Apple processors are little-endian; PowerPC processors (used in modern video game consoles, among other things) are big-endian. Networking protocols, like TCP and IP, almost all use big-endian; big-endian is sometimes called “network byte order”.

Powers of Two#

If we have \(n\) bits, we can represent \(2^n\) different values with them. For example, there are eight different three-bit values:

Powers of two are ubiquitous when talking about cryptography, mainly because they express how many possible \(n\)-bit keys there are, and thus how resistant an algorithm is to brute-force attack.

It’s notable that powers of two grow extremely fast, often at a speed that defies intuition; see Table 1.

For example, \(2^{32}\) is 4,294,967,296 (over 4 billion). That’s already quite a large number by the standards humans are used to thinking about. Just adding eight to the exponent — so \(2^{40}\) — results in a number that’s three digits longer: 1,099,511,627,776 (over 1 trillion).

An important mistake to avoid, if you’re not used to thinking about powers of two, is thinking that doubling the exponent doubles the result. \(2^{64}\) isn’t two times larger than \(2^{32}\); it’s four billion times larger. In fact, \(2^{64}\) is a 20-digit number2To be exact, it’s 18,446,744,073,709,551,616..

128-bit and 256-bit keys are commonly used with symmetric ciphers. \(2^{128}\) keys is far too many to allow for a practical brute-force attack, so it’s considered a secure key size. \(2^{256}\) is 77 digits long, and there’s a plausible argument that it’s physically impossible to try that many keys. There may not be enough energy in the entire universe to even count that high, let alone run a cipher that many times.

\(N\) |

Rough idea of size |

\(N\) seconds is… |

|---|---|---|

\(2^4\) |

Number of students in this class |

16 seconds |

\(2^8\) |

Capacity of one Green Line train |

4 minutes |

\(2^{10}\) |

Capacity of a large theater |

17 minutes |

\(2^{16}\) |

Number of students at Northeastern |

18 hours |

\(2^{32}\) |

Half the world population |

136 years |

\(2^{40}\) |

Inches from Sun to Earth |

34,842 years |

\(2^{64}\) |

Inches from Sun to nearest other star |

Ten times the age of the universe |

\(2^{128}\) |

Number of atoms in Lake Erie |

Completely inconceivable |

\(2^{256}\) |

Number of atoms in the universe |

Completely inconceivable |

Character Encodings#

We’ve seen how integers are represented as bits, but what about letters and text? There is a huge variety of ways to represent text as bits, and each way is called a character encoding, or just “encoding”. Roughly speaking, an encoding specifies a mapping between characters (letters, digits, punctuation, symbols, etc.) and byte sequences.

The simplest one we’ll deal with is called ASCII (pronounced “ass-key”). ASCII provides mappings for 128 different characters; each character maps to a single-byte sequence. (Remember that one byte is eight bits; therefore one byte can take on \(2^8 = 256\) different values. The first bit of any ASCII-encoded byte is zero.) Table 2 has a few examples of ASCII mappings.

Character |

ASCII byte |

|---|---|

A |

|

B |

|

a |

|

b |

|

? |

|

% |

|

Space |

|

\(\sim\) |

|

ASCII includes most of the characters commonly used in English, but its 128 mappings are inadequate for most other languages. It does not include accented characters like à or ü, let alone other writing systems like Greek, Arabic, or Chinese, or mathematical symbols like \(\leq\), or emoji.

The modern standard that captures how to encode all of those things, and more, is called Unicode. Unicode itself is not a single character encoding, but rather a mapping of characters to code points, which are just numbers. It specifies code points for, at the latest counts, 144,697 characters. This includes characters from most of the world’s written languages, plus a huge range of symbols, icons, and emoji. Code points are generally written as “U+” followed by four or five hex digits.

Unicode additionally defines several ways to express code points as byte sequences: these are, in essence, character encodings.

Character |

Code point |

UTF-8 bytes |

|---|---|---|

A |

U+0041 |

|

B |

U+0042 |

|

a |

U+0061 |

|

b |

U+0062 |

|

à |

U+00E0 |

|

ü |

U+00FC |

|

\(\pi\) |

U+03C0 |

|

\(\Sigma\) |

U+03A3 |

|

大 |

U+5927 |

|

樹 |

U+6A39 |

|

\(\mathbb{Z}\) |

U+2124 |

|

\(\oplus\) |

U+2295 |

|

The most commonly-used Unicode encoding is UTF-8. It is a variable-length encoding, which means that it encodes different characters to byte sequences of different lengths. One reason for its widespread use is that it is backward compatible with ASCII — all ASCII-encoded byte sequences are valid UTF-8 sequences that encode the same characters. See Table 3 for a few examples of Unicode code points and their UTF-8 equivalents.

Note that there is a huge amount of detail in Unicode that we’re skipping over. This is not a course about Unicode, and this is all the information about Unicode that you’ll need in this course.

You may also see the encoding ISO-8859-1, also known as Latin-1. It has mappings for 256 characters, each one byte long. It is backward compatible with ASCII.

In any context where there is a conversion between characters and bytes, there should be an encoding specified. For example, when you create a text file using a program like Notepad (on Windows) or TextEdit (on macOS), the program will need to convert the characters you typed to a sequence of bytes to write to disk. In the Save dialog, there is an option to choose an encoding. UTF-8 is usually the default, in this and in all contexts where an encoding must be chosen.

In this course, if we need to convert between text and bytes, we’ll keep things simple: we’ll restrict ourselves to the first 128 Unicode code points, so that it doesn’t matter if we encode using ASCII or UTF-8.

Modular Arithmetic#

Modular arithmetic is a type of math that works with integers. The core idea of modular arithmetic is to replace integers with their remainder when divided by some positive integer \(m\), called the modulus. We’ll be seeing plenty of modular arithmetic later in the course, and we’ll go into more depth as needed. For now, we’ll just cover the basic idea and the notation, since it shows up everywhere.

Divisibility#

The concept that underlies modular arithmetic is divisibility. You likely already have an intuitive understanding of what it means for one number to evenly divide another, but here is the formal definition.

Let’s say we have two integers, \(k\) and \(n\). If it’s possible to write the equation \(k = n \times q\), where \(q\) is an integer, then we say that \(n\) evenly divides \(k\). Mostly, we just say that \(n\) divides \(k\), omitting the “evenly”. There are a few other ways to state the same fact:

\(n\) is a factor of \(k\).

\(k\) is a multiple of \(n\).

\(k\) is divisible by \(n\).

If it is not possible to write such an equation, then \(n\) does not evenly divide \(k\).

The remainder of dividing \(k\) by \(n\) is the integer you would have to subtract from \(k\) to get something that is divisible by \(n\). If \(k\) is already divisible by \(n\), then the remainder is zero. Otherwise, the remainder is greater than zero and less than \(n\).

For example, consider \(n = 5\) and \(k = 32\). \(n\) does not divide \(k\). The remainder is 2, because if we subtract 2 from 32, we get a number that is divisible by 5: \(32 - 2 = 30 = 5 \times 6\).

Consider \(n = 6\) and \(k = 42\). We can write \(42 = 7 \times 6\), so 6 divides 42. The remainder of dividing \(k\) by \(n\) is zero.

The greatest common divisor, or GCD, of two integers is the largest integer that evenly divides both of them. For example, the GCD of 15 and 27 is 3. The mathematical notation for this is \(\gcd(15, 27) = 3\). The GCD can be computed quickly, even for extremely large numbers, using an algorithm called the Euclidean algorithm. Its details aren’t important here, but they’re explained in the appendix.

Notation#

We denote the remainder when dividing \(k\) by \(n\) as “\(k \Mod n\)”, read as “\(k\) modulo \(n\)”. For example, \(17 \Mod 5 = 2\), because dividing 17 by 5 leaves a remainder of 2. Recall that the remainder is always greater than or equal to zero, and less than the divisor, in this case 5.

Another way to write this is as a congruence. Note the three-bar equals sign; this is read as “congruent to”. The parenthetical to the side indicates that the expressions on both sides of the congruence leave the same remainder when divided by 5:

Another way to define modular congruences is to say that \(a \equiv b \pmod{n}\) means that \(a - b\) is evenly divisible by \(n\).

Modular arithmetic is sometimes referred to as “clockface arithmetic”. Arithmetic on clocks happens modulo 12. For example, if it’s 11 o’clock, what time will it be 3 hours from now? \(11 + 3 = 14\), which leaves a remainder of 2 when divided by 12: it will be 2 o’clock.

We sometimes refer to reduction modulo \(n\). To reduce an integer modulo \(n\), we simply replace it by its remainder when divided by \(n\). “Addition modulo \(n\)” is standard addition, followed by reducing the result modulo \(n\). Multiplication modulo \(n\) is similar: multiply two integers together as normal, then reduce the result modulo \(n\).

As we saw, computers represent numbers with a finite number of bits. As such,

computer arithmetic is implicitly modular. For example, in Java, the int type

is 32 bits wide, and all addition and multiplication on them is implicitly

modulo \(2^{32}\).

Bitwise Operations#

There are two mathematical operations on bits that are fundamental to many cryptographic algorithms.

XOR#

The bitwise exclusive-OR operation3You may see bitwise XOR referred to as “bitwise addition modulo 2” or “bitwise addition without carry”, which are both reasonable alternative ways to view the operation. (“XOR” for short) takes two integers as

input, and produces a single integer as output. We denote it with the symbol

\(\oplus\). In most common programming languages, including Java and Python, the

bitwise XOR operator is ^ (caret), which is shift-6 on US English

keyboards.

This is the truth table for the XOR operation on one-bit inputs:

\(a\) |

\(b\) |

\(a \oplus b\) |

|---|---|---|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

In words, \(a \oplus b\) is 1 if exactly one of the inputs is 1. It is 0 if both inputs are 1, or neither input is 1.

We extend the operation from single bits to integers of any bit width by applying the one-bit XOR operation to pairs of bits with the same multiplier. As an example, let’s compute the bitwise XOR of the eight-bit integers 157 and 86. We start by writing them in base 2, aligned one above the other so that bits with the same multiplier line up (ones bit with ones bit, twos bit with twos bit, and so on):

To compute the result, we apply the XOR truth table above to each column, and write the output bits below.

Converting the base-2 number below the line to base 10, we get a result of 203. Therefore, \(157 \oplus 86 = 203\).

There are four crucial mathematical properties of XOR:

Any number XORed with itself results in zero. In math terms: for any \(a\), \(a \oplus a = 0\).

Any number XORed with zero results in itself. In math terms, for any \(a\), \(a \oplus 0 = a\).

XOR is commutative, meaning that the order of the operands doesn’t matter. In math terms: \(a \oplus b = b \oplus a\).

XOR is associative, meaning that changing the order in which you perform a chain of XOR operations doesn’t change the result. In math terms: \((a \oplus b) \oplus c = a \oplus (b \oplus c)\).

Together, these properties make XOR an easy operation to “undo”. We can transform one integer into another by XOR’ing it with some integer \(k\), and get the original integer back by XOR’ing the result with \(k\) again. Call the original integer \(a\), and let \(b = a \oplus k\). Now we show that \(b \oplus k = a\):

Step |

Reasoning |

|---|---|

\(b \oplus k\) |

|

\(= (a \oplus k) \oplus k\) |

by definition of \(b\) |

\(= a \oplus (k \oplus k)\) |

by associativity |

\(= a \oplus 0\) |

any number XOR itself is zero |

\(= a\) |

any number XOR zero is itself |

Another important property is that the bit width of \(a \oplus b\) is, at most, the bit width of the wider of \(a\) and \(b\). In other words, if you XOR two numbers that each fit in one byte, the result will also fit in one byte.

All of these properties make XOR a very important building block. We’ll see it in most ciphers and hash functions. You certainly don’t need to be able to calculate it in your head, but it’s important that you have the intuition for how XOR is self-inverting, and XOR with zero does nothing.

Shifts and Rotations#

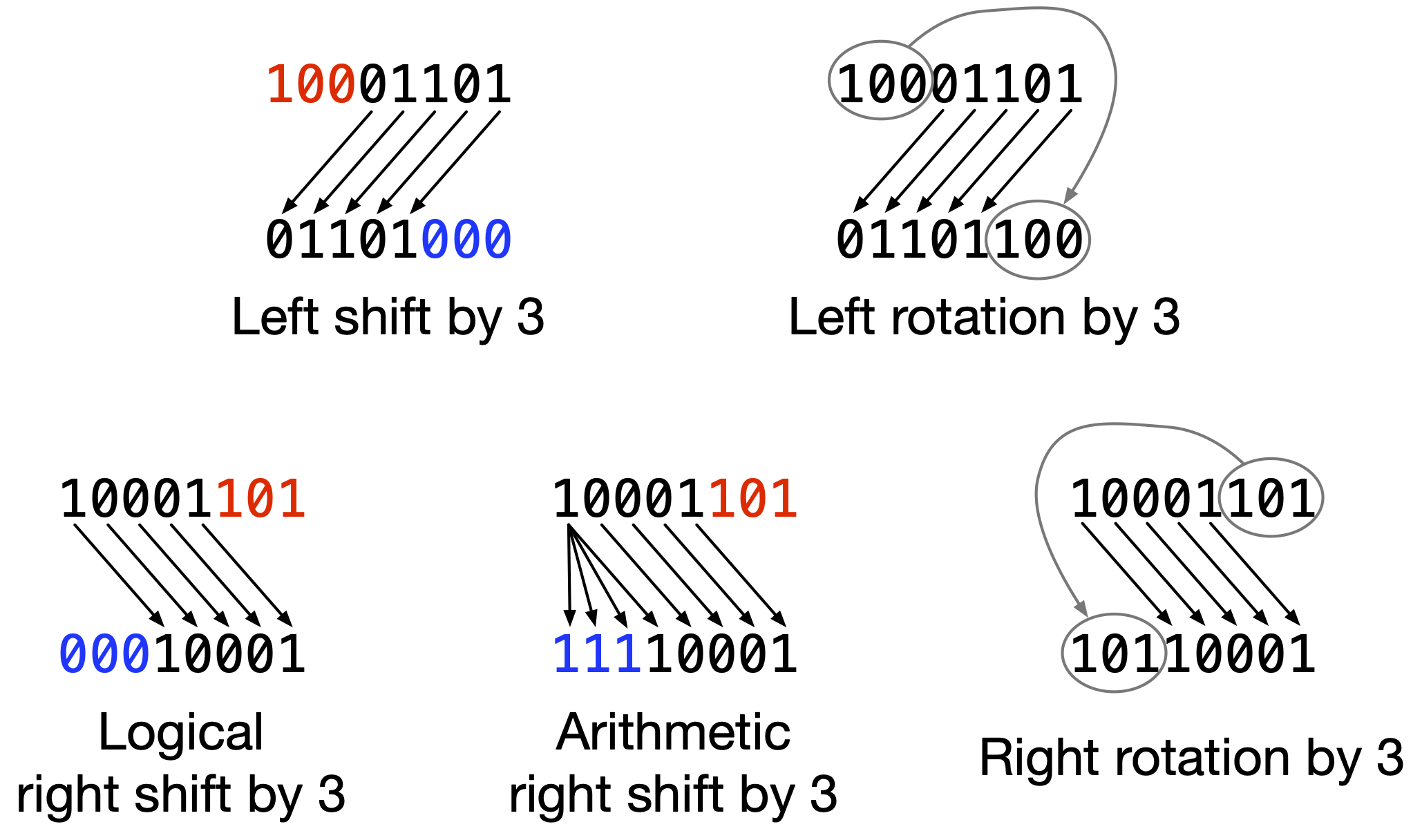

Another common operation in cryptographic algorithms is bitwise rotation.

First, we have to define bitwise shifts. This operation is defined with respect to a certain bit width; in these examples, we’ll use 8 bits. Shifts can be either to the left or the right, and involve sliding the bits of a number in that direction, cutting off bits that slide off the end, and filling in the vacant space on the other end.

In left shifts, the bits that fill in the vacant space are always all zero. For

example, consider the base-2 number 10001101. Shifting it left by 3 results in

01101000. The leftmost five bits, 01101, are from the input; the rightmost

three bits are filled in with zero bits. The leftmost bits of the input, 100,

are dropped.

There are two types of right shift, logical and arithmetic. In logical shifts, the vacant space on the left is filled with zero bits. In arithmetic shifts, the vacant space is filled with whatever the leftmost bit of the original number is4The reason why this behavior is desirable has to do with the way computers represent negative numbers, which we won’t get into here.. Any time you hear about a right shift, it should be specified whether it is logical or arithmetic.

Logical-shifting the base-2 number 10001101 to the right by 3 bits results in

00010001. The rightmost five bits, 10001, are from the input; the leftmost

three bits are filled with zero bits and the rightmost bits of the input, 101,

are dropped.

Arithmetic-shifting 10001101 to the right by 3 bits results in 11110001. The

rightmost five bits are the same as in the logical-shifted version. However,

because the leftmost bit of the input was 1, the vacant space on the left is

filled with ones instead of zeroes.

The shift operators in most common programming languages, including Java, are

<< for left shift and >> for right shift; for example, n << 2 is the

variable n shifted left by 2 bits. In Java specifically, >> is arithmetic

right shift and >>> is logical right shift.

Bitwise rotation is also defined with respect to a certain bit width, and can be either to the left or the right. Rotation differs from shifting in that the bits that are slid off the end are moved around to the vacant space on the other end, instead of being dropped.

For example, rotating the base-2 number 10001101 to the left by 3 bits results

in 01101100. The three high-order bits of the input, 100, instead of being

dropped, are put back on the right, to fill the vacant space. Rotating

10001101 to the right by 3 bits results in 10110001: the three low-order

bits 101 are moved to the left end.

There is no distinction between logical and arithmetic right rotations, because there is no vacant space to be filled with something other than the bits of the input itself. Also, note that left rotation by \(k\) bits is the same as right rotation by \(n-k\) bits, where \(n\) is the bit width of the input.

See Fig. 2 for examples of all types of shifts and rotations.

Fig. 2 Examples of shifting and rotating the bits 10001101. Red marks input digits that get dropped. Blue marks “new” digits that do not come from the input.#

Most programming languages don’t have built-in rotation operators. Java has

standard library methods to do rotation: Integer.rotateLeft() and

Integer.rotateRight(), and similar methods for other integral types.

The XOR Cipher#

Above, we saw that if you XOR two integers \(a\) and \(b\) together, then XOR the result with \(b\) again, you’ll get back \(a\).

This property makes it easy to build a very simple symmetric cipher with XOR. Choose a sequence of bytes as a key. To encrypt, XOR the key with the plaintext, byte by byte, repeating the key if it’s shorter than the plaintext. Decryption is the same: XOR the key with the ciphertext, byte by byte, repeating the key as necessary.

Caution

This is not a secure cipher in the slightest. We’re only looking at it here as a foundation for other concepts.

As an example, we’ll encrypt the phrase This is the plaintext with the key Secr3t.

Key S e c r 3 t

Key ASCII bytes (hex) 53 65 63 72 33 74

Plaintext T h i s i s t h e p l a i n t e x t

Plaintext ASCII bytes 54 68 69 73 20 69 73 20 74 68 65 20 70 6c 61 69 6e 74 65 78 74

Repeated key 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63

Ciphertext 07 0d 0a 01 13 1d 20 45 17 1a 56 54 23 09 02 1b 5d 00 36 1d 17

Each ciphertext byte is the XOR of the two bytes lined up directly above it. For example, the first byte of ciphertext is the first byte of plaintext (0x54) XORed with the first byte of the key (0x53); the result is 0x07. Notice that the “Repeated key” line consists of the six-byte key, repeated over and over.

To recover the original plaintext from the ciphertext, we XOR the bytes from the “Repeated key” line with the ciphertext, byte by byte:

Ciphertext 07 0d 0a 01 13 1d 20 45 17 1a 56 54 23 09 02 1b 5d 00 36 1d 17

Repeated key 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63 72 33 74 53 65 63

Decrypted plaintext 54 68 69 73 20 69 73 20 74 68 65 20 70 6c 61 69 6e 74 65 78 74

Cryptanalysis#

The repeating-key XOR cipher is extremely easy to break, even in a ciphertext-only attack. (With known or chosen plaintext, you can simply XOR the plaintext and ciphertext together to recover the key.) Because it’s so easy to break, it is never used in practice. However, we’re going to look at the attack technique in detail, because the same idea can apply to real-world ciphers if they’re used incorrectly. We’ll see that later in this chapter.

There are two parts to the ciphertext-only attack: first, determining the length of the key; and second, finding the most likely value for each key byte.

How do we determine the length of the key? We start with the insight that we can generally expect two plaintext bytes to be more similar to each other than two random bytes, or a plaintext byte and a random byte. We have a concrete way to measure how similar two bytes are: when you XOR them together, how many 1-bits are in the result? The lower the count of 1-bits, the more similar the bytes were. The number of 1-bits in the result of XORing two bytes is called the Hamming distance between those two bytes.

Consider encrypting two plaintext bytes by XORing them with the same key byte. We would have \(C_1 = P_1 \oplus K\) and \(C_2 = P_2 \oplus K\). If we XOR these two ciphertext bytes together, we get \(P_1 \oplus K \oplus P_2 \oplus K\), which simplifies to \(P_1 \oplus P_2\). In effect, the key byte is canceled out, and we’re left with a value that is just the two plaintext bytes XORed together. Therefore, the Hamming distance between \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) is equal to the Hamming distance between \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). And because of the above insight about similarity of plaintext bytes, we can expect that Hamming distance to be lower than average5The average Hamming distance between two random bytes is 4: half the number of bits in a byte..

By contrast, consider XORing two plaintext bytes with different key bytes, \(K_1\) and \(K_2\). XORing the resulting two ciphertext bytes together, we would have \(P_1 \oplus K_1 \oplus P_2 \oplus K_2\). No cancellation of key bytes would happen, and thus the result would be roughly random. We can expect the Hamming distance between the two ciphertext bytes, then, to be close to average.

We can use all that to determine the likely key length. We evaluate many candidate key lengths. For each one, we split up the ciphertext into blocks of that size, and compute the Hamming distances between adjacent pairs of blocks, byte-by-byte. When we test the correct key size (or a multiple of it), we’ll be computing Hamming distances between pairs of ciphertext bytes that were encrypted with the same key byte. Therefore, we’ll effectively be computing Hamming distances between pairs of plaintext bytes, and should get a lower-than-average result. By contrast, when we test an incorrect key size, we’ll effectively be computing Hamming distances between random bytes, and should get a close-to-average result.

Once we determine the key length, how do we find the actual key?

Imagine we knew that the key was only a single byte long. Then the attack would be very simple: we’d try decrypting with every possible key — being one byte long, there would only be 256 possible keys — and see which one resulted in the most plausible plaintext. We’d determine that by using context knowledge about what format the plaintext was likely to be in. For example, if we expected the real plaintext to be ASCII-encoded text, we’d see how many bytes of each candidate plaintext were ASCII encodings of alphanumeric characters.

Now, imagine we knew that the key was six bytes long. That means that the first, seventh, thirteenth, nineteenth, etc. bytes of plaintext were all XORed with the first key byte to produce the corresponding ciphertext bytes. Therefore, all we need to do is to pick out the first, seventh, thirteenth, etc. bytes of ciphertext, put them together, and solve that as if it were the ciphertext of a single-byte key XOR cipher encryption, using the technique above. That will give us the first byte of the six-byte key. To get the second key byte, we do the same thing with the second, eighth, fourteenth, etc. bytes of ciphertext. And so on, with the rest of the key.

Let’s go through the example of decrypting the following ciphertext (shown as hex):

8f fa bc 3d 61 6c d4 a2 fa b3 78 6a 6d c6 e6 b2

b7 3d 68 28 d7 a9 a8 f2 35 7d 28 c2 ae b5 b7 74

24 7b de e6 93 f2 3c 61 6b d8 a2 bf b6 78 70 67

91 a1 b5 f2 2c 6b 28 fc a9 a8 b5 39 6a 7e d8 aa

b6 b7 78 73 60 d8 a5 b2 f2 31 77 28 c6 ae bb a6

78 70 60 d4 bf fa b1 39 68 64 d4 a2 fa 81 30 61

64 d3 bf ac bb 34 68 6d 91 af b4 f2 2c 6c 67 c2

a3 fa b6 39 7d 7b 9f e6 89 bd 74 24 41 91 b2 b3

b7 3c 24 69 df e6 b5 bc 31 6b 66 91 b2 b5 f2 35

7d 28 d3 a3 b6 a6 78 73 60 d8 a5 b2 f2 2f 65 7b

91 b2 b2 b7 78 77 7c c8 aa bf f2 39 70 28 c5 ae

bf f2 2c 6d 65 d4 e8 fa 9c 37 73 24 91 b2 b5 f2

2c 65 63 d4 e6 ae ba 3d 24 6e d4 b4 a8 ab 78 67

67 c2 b2 fa b3 78 6a 61 d2 ad bf be 76 24 49 df

a2 fa bb 36 24 7c d9 a9 a9 b7 78 60 69 c8 b5 f6

f2 36 6d 6b da a3 b6 a1 78 6c 69 d5 e6 aa bb 3b

70 7d c3 a3 a9 f2 37 62 28 d3 b3 b7 b0 34 61 6a

d4 a3 a9 f2 37 6a 28 96 a3 b7 fc 78 26 4f d8 b0

bf f2 35 61 28 d7 af ac b7 78 66 6d d4 b5 fa b4

37 76 28 d0 e6 ab a7 39 76 7c d4 b4 f6 f0 78 7d

67 c4 e1 be f2 2b 65 71 9f e6 94 bd 2f 28 28 c6

ae bf a0 3d 24 7f d4 b4 bf f2 2f 61 37

First, we’ll determine the length of the key. We’ll test key lengths from 2 up to 25. For each candidate length, we break up the ciphertext into blocks of that length, and compute the Hamming distances between adjacent blocks. Fig. 3 shows the results.

Fig. 3 Average Hamming distances for key lengths 2 through 25.#

These are computed by (1) computing Hamming distances between adjacent pairs of blocks; (2) dividing each distance by the length of the block, to get a per-byte average distance; (3) averaging those average distances across all block pairs. The resulting numbers can be interpreted as “the average number of different bits per byte”.

Notice a very clear pattern: the average Hamming distances when assuming key lengths of 7, 14, or 21 are much lower than for all other key lengths. They all have distances of less than 3, while the distances for other key lengths hover around 4. That means the repeated key is highly likely to be 7 bytes long. The low Hamming distances at 14 and 21 are because those are multiples of 7: any repeating 7-byte sequence is also, by nature, a repeating 14-byte or 21-byte sequence.

Let’s assume the key is 7 bytes long, then, and solve each byte individually. To solve the first byte, we’ll pick out every seventh byte of ciphertext, starting from the first one:

8f a2 e6 a9 ae e6 a2 a1 a9 aa a5 ae bf a2 bf af

a3 e6 b2 e6 b2 a3 a5 b2 aa ae e8 b2 e6 b4 b2 ad

a2 a9 b5 a3 e6 a3 b3 a3 a3 b0 af b5 e6 b4 e1 e6

ae b4 c6

We’ll XOR those bytes with every possible single byte, and see how many of the resulting bytes are ASCII encodings of alphabetic characters or the space character. The results are in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 The percentage of candidate plaintext bytes that are ASCII-alphabetic, for each candidate single-byte key.#

There’s a clear winner: the one point all by itself near the top. The candidate key byte that resulted in the highest proportion of the plaintext being ASCII-alphabetic is 198, or 0xc6. We’ll assume that is our actual first key byte.

We’ll repeat this procedure with every seventh byte of ciphertext starting from the second one, which results in the byte value 0xda. We continue this until we’ve gotten all seven bytes of the key. The result is:

c6 da d2 58 04 08 b1

We try decrypting the whole ciphertext with that key, and the result is a coherent, ASCII-encoded, English plaintext. Decrypt it yourself to see what it says.

The point of going through this example is to demonstrate how easy it is to break the XOR cipher. The whole process above can be implemented in less than 100 lines of code, and runs in a fraction of a second. It was made especially easy by the fact that the plaintext was almost entirely alphabetic ASCII bytes; not all real-world plaintexts are like that. But even with less friendly plaintexts, the attack isn’t significantly harder. Keep this in mind as you read on.

One-Time Pad#

In the introduction, we saw that all ciphers are vulnerable to brute-force attack: simply trying every possible key. That wasn’t quite true, because there is one exception: the one-time pad.

The one-time pad is simply the XOR cipher, but with a randomly generated key that is, crucially, the same length as the plaintext. The key can never be reused, or else the scheme degenerates into the insecure XOR cipher; this is where the “one-time” part of the name comes from.

The key being the same length as the plaintext is what makes brute force impossible. One reason is that that means keys are generally very long and thus too numerous to brute-force. But there’s another reason why brute force is impossible against the one-time pad. It’s not just impossible in practice, but in theory too. Even with infinite computing power, you still couldn’t do it.

If you try decrypting one-time-pad ciphertext with all possible keys, the result will be all possible plaintexts. There is no way to tell which plaintext is the right one, and thus no way to tell which key is the right one. For example, suppose I’ve encrypted a message with a one-time pad, and the resulting ciphertext is these bytes (in hex):

af c9 32 6b 4b 92 8a af 66 33 81 06 1f 06 1b 5c

If you decrypt that with the key bytes e2 ac 41 18 2a f5 ef 8f 07 46 f5 6e 7a 68 6f 35 cc a8 46 02 24 fc, you get the ASCII encoding of this string:

Message authentication

If you instead decrypt with the key bytes fc b9 5b 0f 2e e0 aa df 0f 54 ad 26 6c 76 72 38 ca bb 12 1b 22 f5, you get the ASCII encoding of this string:

Spider pig, spider pig

If you tried every possible 22-byte key, you would see every possible 22-byte plaintext. This is the fundamental reason why the one-time pad is the only perfect cipher in existence.

However, the need for communicating parties to share a large amount of key material ahead of time means the one-time pad isn’t suitable for practical use. If the parties run out of key material and cannot meet in person to exchange more, they’re stuck. Thus, the one-time pad is not used outside of a few highly specialized applications in military and espionage settings6For these settings, another possible advantage of the one-time pad is that it is simple enough to compute on paper, without a computer..

Key Takeaways#

Hexadecimal (base-16) notation is very commonly used to represent numbers in computing. Two hex digits correspond exactly to one byte.

There are two ways to convert between larger-than-a-byte numbers and sequences of bytes: big-endian and little-endian. Both are commonly used in practice.

Character encodings are ways of representing text and characters as sequences of bits. The most common one on the Internet, UTF-8, is part of the Unicode standard.

Modular arithmetic is a form of arithmetic on integers that involves replacing integers with their remainder when divided by some other integer, the modulus.

The Euclidean algorithm can compute the greatest common divisor of two integers. It works quickly even on extremely large numbers.

Bitwise XOR is an operation to combine two numbers into one. It is very commonly used in cryptography. It has the useful property that every integer is its own inverse.

Bitwise rotations involve modifying an integer by sliding its bits around. It is also commonly used in cryptography.

The XOR operation can be used to build a very simple symmetric cipher. However, this cipher is trivial to break in a ciphertext-only attack.

The one-time pad is the only perfectly secure cipher in existence. It is a version of the XOR cipher where the key is as long as the plaintext. It cannot be broken, even by brute force, but is too impractical to actually use.